This research roundup about vaccine hesitancy was last updated on Jan. 25, 2022.

Even though nearly three-fourths of adults in the U.S. had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine as of early September, vaccine hesitancy remains an important public health concern worldwide, hampering efforts to contain the pandemic.

Although not a new phenomenon, the topic has taken on a greater urgency because of the pandemic. Researchers are trying to understand what it takes to change the minds of individuals who are still not convinced they should get the COVID-19 vaccine for themselves or their eligible children.

This has prompted a surge in studies that aim to better understand why people are vaccine hesitant and what it takes to increase their confidence in the COVID-19 vaccines. At the end of 2020 there were 92 studies on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy posted on the National Library of Medicine’s PubMed research database. As of Sept. 3, that number had climbed to 751.

To help journalists with their reporting, we’ve gathered several data sources and research studies that shed light on wider trends in vaccine hesitancy and explore the reasons why certain groups remain wary of COVID-19 shots.

What is vaccine hesitancy?

Vaccine hesitancy refers to a continuum of beliefs and behaviors around whether or not to get vaccinations. The World Health Organization defines vaccine hesitancy as a “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccine services.” The organization listed vaccine hesitancy as one of the top 10 threats to global health in 2019, before the pandemic arrived.

Vaccine hesitancy is a global phenomenon and it’s complex.

Many factors feed into vaccine decision-making, according to the federal May 2021 report, “COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy: Demographic Factors, Geographic Patterns, and Changes Over Time.” They include cultural norms, social and peer influences, political views, concerns about specific vaccines and other factors that are specific to an individual or group, the report explains.

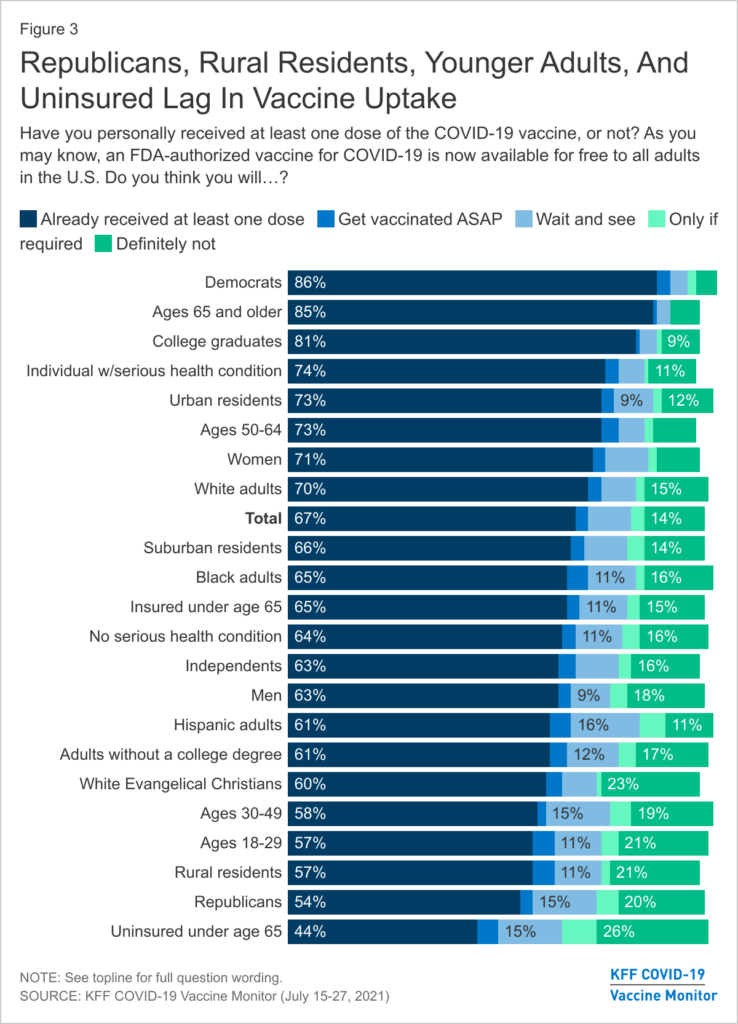

Some common reasons for vaccine hesitancy include beliefs that vaccines are not safe or effective, increased concerns about rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines and lack of trust in the government, polls and studies show. Political affiliation has also been associated with vaccine hesitancy rates. Republicans and people who live in politically conservative states are more likely to be vaccine hesitant, various polls and studies have shown.

But within each group, down to the individual level, reasons for vaccine hesitancy vary. Experts caution against overgeneralizing when reporting on vaccine hesitancy trends.

“People don’t have a kind of amorphous hesitation or reluctance to get vaccinated or to receive medical care,” said Dr. Rhea Boyd, a pediatrician, scholar and child health advocate in California, during an August online briefing hosted by the Alliance for Health Policy, a nonprofit think tank. “You have to do the extra work to actually understand why folks aren’t vaccinated.”

In addition, used without context, the term “vaccine hesitancy” might imply a conscious decision to delay or avoid vaccines when, actually, some people face significant barriers to getting them.

For some, it’s a challenge to find transportation or take time off from work to receive the two-dose COVID-19 vaccines.

“People know [the vaccine] is free,” said Boyd. “It’s that obtaining health care in this country has never been cost-neutral. Getting to that vaccination site requires gas in your tank. It requires [taking a] bus. It might require a parking fee. Getting to and from health care always costs money and that is a concern for people who are low income.”

Most websites that track vaccination trends in the U.S. show that the percentage of Americans who are unsure about getting the COVID-19 vaccine is steadily dropping. The Food and Drug Administration’s recent full authorization of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine could further encourage more U.S. adults to get vaccinated. The rapid spread of the Delta variant has also played a role. A recent analysis by Bloomberg shows an increase in vaccinations in July and August, particularly among Black and Hispanic Americans, after the highly-infectious Delta became the predominant variant of COVID-19 spreading in the U.S.

It may not be easy to sway the opinions of a small percentage of the people who staunchly oppose vaccinations or have made up their minds to not get COVID-19 vaccines. But journalists can play an important role in informing those who are still on the fence. Researchers sometimes refer to this group as the “moveable middle.”

Research roundup

This section includes summaries of systematic reviews and research that delve into drivers of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and topics such as vaccine confidence among Black Americans, vaccine hesitancy among health care workers, and changing attitudes about the vaccine.

Hesitant or Not Hesitant? A Systematic Review on Global COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance in Different Populations

Maria Giulia Salomoni; et al. Vaccines, August 2021.

The paper, which is a review of 100 studies published in academic journals in English between November 2020 and March 2021, provides an overview of vaccine hesitancy trends in general population and specific populations like people with chronic diseases and health care workers in several countries. Its findings reveal “remarkable differences in vaccine acceptance rates can be observed across countries and subpopulations, supporting the underlying complex and unpredictable interplay among demographic, geopolitical and cultural aspects, which are hard to be understood and discriminated,” the authors write.

For instance, the analysis shows that among health care workers in the countries studied, the lowest vaccine confidence rate was reported in the Democratic Republic of Congo at 27.7%, followed by the U.S. at 36%.

The highest vaccine confidence rate among health care workers was reported in Asia — in a region comprising China, India, Republic of Indonesia, Singapore, Vietnam and Bhutan — at 96.2%.

The authors note that health care workers involved in direct patient care were found to be more confident in vaccines, suggesting that higher vaccine hesitancy “could be related to a less direct contact with the patient and, consequently, a reduced risk perception of COVID-19 associated morbidity.”

COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy—A Scoping Review of Literature in High-Income Countries

Junjie Aw, Jun Jie Benjamin Seng, Sharna Si Ying Seah and Lian Leng Low. Vaccines, August 2021.

The study summarizes findings from 97 studies published in English about the rates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its determinants in high-income countries or regions with a gross national income of $12,536 or more per capita. The authors conducted their search between December 2019 and March 2021.

Nearly half of the studies show COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy of 30% or more in their study populations, the authors report.

Overall, some of the factors associated with vaccine hesitancy include being female, younger, being a racial or ethnic minority and having lower levels of education. (While the study doesn’t specify the age, various polls have shown that young adults under the age of 30 are more likely to be vaccine hesitant.)

Several studies show that use of social media or Internet as the main source of information or the lack of widely accessible information on COVID-19 vaccines were linked with vaccine hesitancy.

Other factors associated with vaccine hesitancy included being health care workers in non-clinical roles, giving higher importance to religion, living in rural areas and reduced trust in government and the pharmaceutical industry.

Twenty-eight studies show that having had the flu vaccine is the most common determinant associated with lower vaccine hesitancy.

Countries with the highest vaccine hesitancy rates included United Arab Emirates, U.S., Hong Kong and Italy, researchers find. “Compared to low-income countries or regions, the current vaccine hesitancy rates in high income countries or regions are worrisome,” they write.

Racial/Ethnic Differences in COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Among Health Care Workers in 2 Large Academic Hospitals

Florence M. Momplaisir; et al. JAMA Network Open, August 2021.

The study is based on email surveys of 10,871 health care workers who had clinical roles with patient contact, nonclinical roles with patient contact and nonclinical roles without patient contact, from two academic hospitals — one adult and one children’s — in Philadelphia. The hospitals were not named.

Researchers find that Black participants were five times as likely to be vaccine hesitant, while Hispanic workers were twice as likely and Asian workers 1.5 times as likely to be hesitant compared with white participants.

The survey was conducted during a three-week period in November and December 2020.

Overall, half of respondents were hesitant to get the vaccine. Nearly 70% of vaccine-hesitant health care workers said they didn’t plan on getting the vaccine or weren’t sure if they would, while 32% said they planned to delay vaccination.

Among vaccine hesitant respondents, 87% were concerned with side effects. Other top reasons across race and ethnicities included vaccines being too new and not knowing enough about the vaccines. A higher percentage of Black participants cited concerns with vaccines not working and worried that they may get COVID-19 from the vaccine.

“In addition to reasons for vaccine hesitancy reported here, it is possible that mistrust of the health care system owing to historical mistreatment in research and medical care, particularly in the Black community, may contribute to hesitancy,” the authors write.

Health care workers who were accepting of COVID-19 vaccines said they wanted to protect their family, themselves and their community. They also believed that life won’t get back to normal until most people are vaccinated.

The majority of the survey respondents were white women. More than half were younger than 40 years old. And nearly 60% had a bachelor’s or masters’ degree.

“These results suggest that more work is needed to ensure confidence in COVID-19 vaccination, particularly among Black and Hispanic or Latino individuals, who are disproportionately impacted by the pandemic,” researchers write.

Black Americans Cite Low Vaccine Confidence, Mistrust, and Limited Access as Barriers to COVID-19 Vaccination

Laura Bogart; et al. RAND Corp. research brief, August 2021.

The research brief by RAND Corp., a nonprofit policy think tank, is based on a national online survey of 207 Black adult participants in November 2020 in addition to in-depth interview with 28 of them between December 2020 and March 2021.

Researchers find that even though vaccine confidence has improved among Black Americans, mistrust of the vaccine continues to play a role in lower vaccine uptake.

The authors write, “vaccine-related mistrust is a multifaceted construct that includes distrust of health care and health care providers (to be equitable), the government (to provide truthful information), and the vaccine itself (to be safe and effective).”

They also note that discussions over vaccine hesitancy has masked the persistent access problems, such as long distances to vaccine sites, lack of transportation, lack of high-speed internet access or internet literacy to schedule appointments and work and child-care issues, particularly for two-dose vaccines and when managing potential side effects.

“To improve Black Americans’ confidence in COVID-19 vaccines, and in public health initiatives more generally, health care organizations and the U.S. public health system need to undertake efforts to become more trustworthy,” the authors write. “Being honest about historical and ongoing discrimination and working with communities to provide equitable, accessible care can significantly contribute to such efforts. These steps will improve the health care system’s response not only to the current public health crisis but also to future crises.”

Changing Attitudes Toward the COVID-19 Vaccine Among North Carolina Participants in the COVID-19 Community Research Partnership

Chukwunyelu H. Enwezor; et al. Vaccines, August 2021.

The study is based on a survey of 20,232 individuals in North Carolina, conducted between December 2020 and January 2021, followed by daily surveys of the same respondents to determine vaccine uptake rates until May 2021. Participants completed the surveys using an online application. A quarter of the participants were health care workers.

The initial survey shows that 76.2% of respondents intended to get the vaccine. The most likely respondents to get the vaccine were white males, those living in urban areas and did not work in the health care field. Black Americans were the least likely to show an intent to get the vaccine. The most common reasons for vaccine hesitancy were concerns with the safety and efficacy of the vaccines.

The follow-up surveys through May, meanwhile, “revealed some interesting data about vaccine uptake,” the authors write.

Overall, 92.5% of respondents got the COVID-19 vaccine. Of those who intended to get the vaccine, uptake was 98.5%. Among those who didn’t intend to get the vaccine, uptake was 70%.

“Interestingly, Black Americans who were the least likely to accept the vaccine based on expressed pre-vaccination attitudes had an 88.9% vaccine uptake,” researchers write.

The authors note that their findings point to the dynamic nature of vaccine hesitancy.

“Individuals within this spectrum are not static and may shift across the spectrum over time, depending upon the current social and clinical context and available vaccine options,” they write. “In the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, time is of the essence because the faster we get to herd immunity, the better our chances of avoiding emergence of virulent and evasive variants. Increasing uptake in those in the middle of the spectrum (refuse but unsure, undecided, accept but unsure) may help us achieve herd immunity.”

Uncertainty and Unwillingness to Receive a COVID-19 Vaccine in Adults Residing in Puerto Rico: Assessment of Perceptions, Attitudes, and Behaviors

Andrea López-Cepero; et al. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, August 2021.

The findings are based on 1,911 survey responses between December 2020 and February 2021 collected via an online questionnaire in Google Forms through institutional newsletters, academic groups, organizations, and social network pages to adults living in Puerto Rico. The survey used a convenience sampling approach, which means collecting data from a population that’s easy to reach or contact.

While 82.5% of respondents reported an intent to get vaccinated, 11% said they weren’t sure and 6.5% said they were not planning on getting the COVID-19 vaccine. Those who didn’t plan to get the vaccine or weren’t sure were more likely to be women, be between the ages of 30 and 39, have lower incomes and be more religious. Religiosity was assessed with a question about the importance of religion in the person’s life. Response options ranged from less important to very important.

The most common reasons for vaccine hesitancy were concerns about the vaccines’ safety and efficacy, rigor of vaccine testing and lack of trust in the government, the survey shows. Three-fourths of the respondents were women.

Where to find vaccine hesitancy survey data

Here are several sources that track U.S. attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines. COVID-19 vaccines are currently available to people older than 12 in the U.S.

Kaiser Family Foundation’s COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor

The monitor is an ongoing research project of the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonprofit health policy research group, tracking the Americans’ attitudes and experiences with the COVID-19 vaccines.

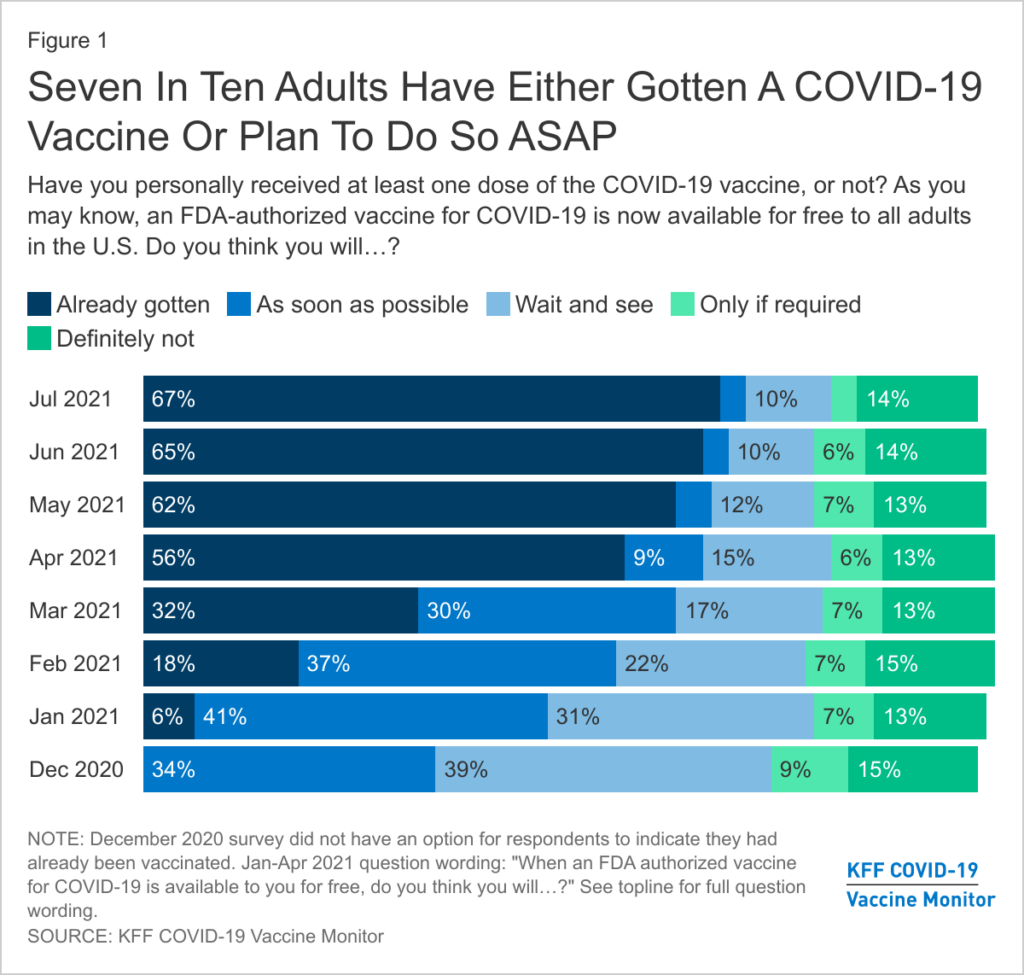

Since the COVID-19 vaccines became available to the public in December 2020, the percentage of adults who said they wanted to wait and see how the vaccine is working before getting vaccinated has dropped from 31% to 10% between January and July of 2021, the Vaccine Monitor shows. Also in July, 3% said they’ll get the vaccine only if required to do so for work, school or other activities, a drop from 7% in January.

But the percentage of adults who have said they will definitely not get the vaccine has remained relatively steady at 14%, if not a bit higher, since January, when it stood at 13%.

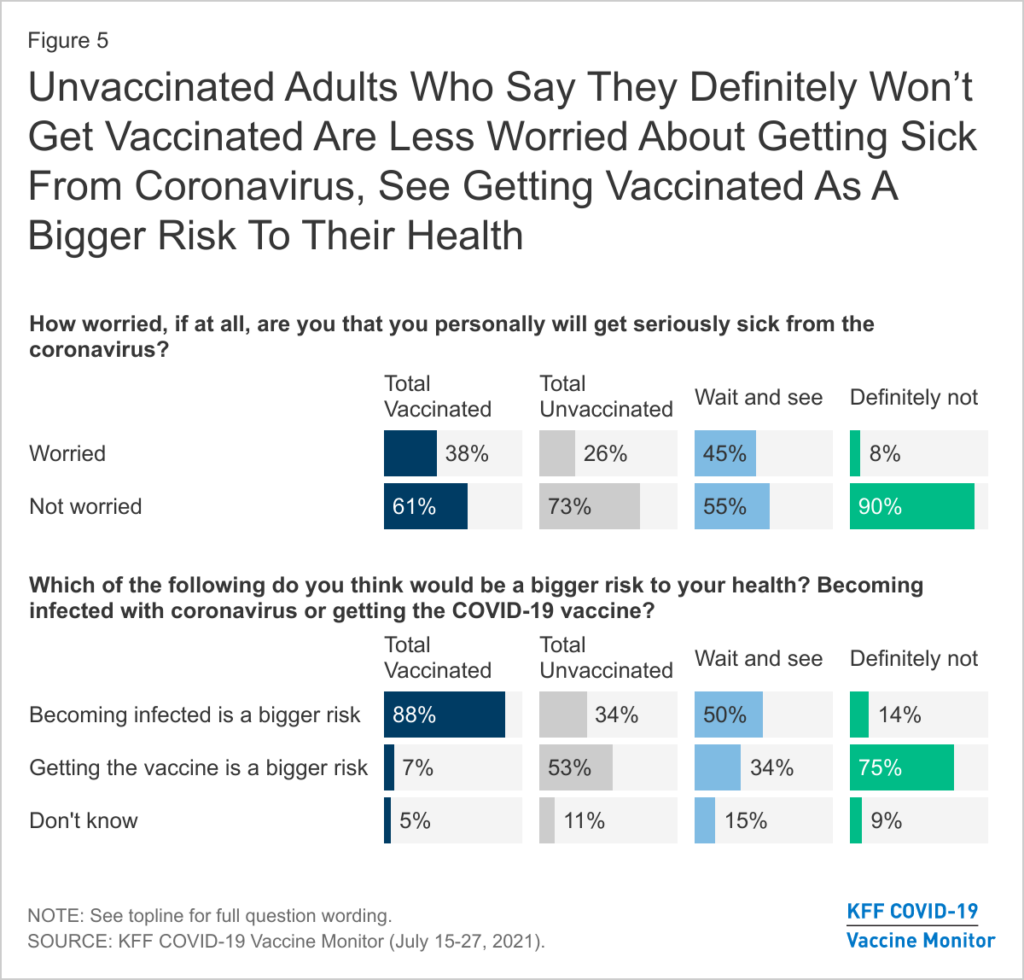

“Unvaccinated adults, especially those who say they will ‘definitely not’ get a vaccine, are much less worried about the coronavirus, the Delta variant, and have less confidence in the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines compared to those who are vaccinated,” write Vaccine Monitor researchers in their report.

Trends in COVID-19 Vaccine Confidence in the US, from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National data, including maps and charts, are updated weekly based on data collected by interviews using a random-digit-dialed sample of cell telephone numbers. The agency’s latest data, collected from 13,901 American adults between Aug. 8-14, 2021, shows that 9% of Americans are unsure about getting the vaccine, a drop from 16.9% in April. Meanwhile, 16% say they probably or definitely will not get the COVID-19 vaccine, a slight drop from 18.3% in April. The overall data also show that people opposed to getting shot are more likely to be under 50 years old, live in rural areas and lack health insurance.

At 38%, American Indians and Alaska Natives had the highest percentage of people among racial and ethnic groups saying that they probably or definitely won’t get vaccinated. They were followed by Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders at 29%. The group with the lowest level of opposition to vaccination were Asian individuals, 1.8% of whom said they probably or definitely won’t get the vaccine.

American COVID-19 Vaccine Poll

The poll is a partnership between the African American Research Collaborative, a collaborative of pollsters, scholars, researchers and commentators committed to bringing an accurate understanding of African American civic engagement to the public discourse, and The Commonwealth Fund, a private foundation that supports health care research. (An expansion of the poll was partially supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, which also supports The Journalist’s Resource.) The pollsters asked more than 12,000 Americans a range of questions to understand who is unvaccinated, why and what could motivate them to get vaccinated. It is one of the largest nationally representative polls of its kind to date, conducted in May and June 2021 using both cell and landline phone numbers, in addition to online questionnaires.

Results are broken down by race and ethnicity, sex, political party affiliation, age, income and education. The poll also parses out vaccine hesitancy, including concerns among the unvaccinated.

Researchers curated a list of concerns with COVID-19, which they had come across at work or seen as part of their research, and presented them to unvaccinated respondents to find out how influential the statements are and which ones are more likely to be associated with not getting the shots. The statements range from clear misinformation (microchips in the COVID-19 vaccines) to political beliefs and personal preferences to other information that may have influenced vaccine uptake, such as facing past discrimination in health care settings, or distrusting the Johnson & Johnson vaccine because of the company’s talc baby powder lawsuits and the very rare blood-clotting condition that could develop after receiving the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine.

Unvaccinated Black respondents cite former President Donald Trump’s administration pushing the vaccines “to approval too quickly without proving their safety,” as one of their top five concerns with the COVID-19 vaccine. Latinos, on the hand, were more likely to say that President Joe Biden’s administration rushed the vaccine.

The survey also breaks down the findings by racial and ethnic subgroups. For example, one of the top concerns among unvaccinated Puerto Rican respondents is the vaccines could make people sick. For Mexican participants, one of the top concerns is the Johnson & Johnson vaccine causing blood clots, even though it has occurred in about 7 per 1 million vaccinated women between 18 and 49 years old and it’s even more rare among women older than 50 and men of all ages, according to the CDC.

Consistent with other findings, the poll shows 44% of vaccine hesitant respondents identified as Republicans and 26% identified as Democrats.

You can learn more about the poll in this video presentation hosted by the Alliance for Health Policy.

U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey COVID-19 Vaccination Tracker

The agency’s Household Pulse Survey measures how the pandemic is impacting households across the country from a social and economic perspective. The survey, conducted every two weeks, includes a question on COVID-19 vaccinations.

The latest survey, based on responses from more than 68,000 respondents, shows more than half of vaccine hesitant Americans cite concerns about side effects as a reason not to get the vaccine. Half say they don’t trust the vaccines. Nearly 43% say they don’t trust the government, 32% say they don’t believe they need the vaccine and 28% say they plan to wait and see if the vaccine is safe.

The data is broken down by age, sex, race and ethnicity, education, health insurance status and having or not having had a COVID diagnosis in the past. Vaccine hesitant individuals are more likely to be under 40 and male, lack bachelor’s degrees and health insurance, and have had a previous COVID-19 diagnosis, the survey shows.

The tracker shows vaccine hesitancy rates by state. In Florida, for example, 3.2% of survey respondents are vaccine hesitant and their top reason is lack of trust in COVID-19 vaccines. In Mississippi, 5.4% of survey respondents are vaccine hesitant and their top concern is vaccine side effects. The vaccine hesitancy rate among California respondents is 1.8%, according to the tracker, and vaccine hesitant individuals’ top concern there is side effects.

COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in the U.S. By County and ZIP Code

The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington School of Medicine and COVID Collaborative, a national assembly of experts, leaders and institutions in health, education and the economy and associations, launched the interactive map in June based on Facebook survey responses from 50,000 Americans.

The map, which is updated every two weeks, shows the estimated percentage of the population that’s vaccine hesitant in each U.S. county and ZIP code and vaccine hesitancy trends over the previous month.

The results are based on the percentage of survey respondents who answered “Yes, probably,” “No, probably not,” or “No, definitely not” when asked “If a vaccine to prevent COVID-19 were offered to you today, would you choose to get vaccinated?”

Vaccine Hesitancy for COVID-19: State, County, and Local Estimates

This report with an interactive map was issued in June by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. It is based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey results from May 26 to June 7, 2021.

The interactive map shows vaccine hesitancy rates by county, the percentage of adults who are fully vaccinated and each county’s overall racial and ethnic makeup. The map is also available on a CDC website.

The Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation also issued a report in May 2021, exploring how vaccine hesitancy evolved in the early months of 2021, as COVID-19 vaccines became more available.

It shows that even though vaccine hesitancy decreased across most demographics between January and March 2021, the percentage of people who remained opposed to vaccines remained relatively unchanged.

This online poll includes roughly 1,000 American adults each week on a variety of coronavirus-issues, including masks and vaccine. Its most recent iteration, published on Aug. 31, 2021, shows that Americans’ opposition to getting the COVID-19 vaccine is at its lowest level since the poll was launched in March 2020.

The percentage of respondents who said they are not likely at all to get the vaccine dropped from 19% in April 2021 to 14% in August.

Notable changes were also seen in parents’ responses about getting their children vaccinated. Within the month of August, fewer parents expressed total opposition to vaccines for their kids: Between Aug. 13-16, 2021, 27% of parents said they weren’t likely at all to get a coronavirus shot for their kids. That percentage dropped to 19% between Aug. 27-30.

The poll is conducted by Axios, an online news website, and Ipsos, a market research and consulting firm.

Further reading

Changes in COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Among Black and White Individuals in the U.S.

Tasleem Padamsee; et. al. JAMA Network Open, January 2022

The survey study of 1,200 U.S. adults, conducted between December 2020 and June 2021, finds that that COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy decreased more rapidly among Black individuals than among white individuals. “A key factor associated with this pattern seems to be the fact that Black individuals more rapidly came to believe that vaccines were necessary to protect themselves and their communities,” authors write.

COVID-19 Vaccination Communication: Applying Behavioral and Social Science to Address Vaccine Hesitancy and Foster Vaccine Confidence

Wen-Ying Sylvia Chou; et. al. National Cancer Institute, December 2020.

6 tips for covering COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy

COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy: What research shows

11 questions journalists should ask about public opinion polls

Need an expert?

Greater Than COVID, a public information campaign by the Kaiser Family Foundation, features physicians, researchers and community health workers of colors who provide facts and dispel misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine in English and Spanish.

CommuniVax, a national coalition of social scientists, public health experts and community advocates working to strengthen national and local COVID-19 vaccination efforts with a focus on communities of color. The coalition is led by the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and by the Department of Anthropology at Texas State University.

Expert Commentary