In January 2001, the office of the U.S. Surgeon General issued a report about mental health disparities affecting racial and ethnic minorities.

“Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity” was a supplement to the Surgeon General’s 1999 report on mental health, and it found that people of color had less access to mental health services, were less likely to receive those services when needed, often received poorer quality of care and were underrepresented in mental health research.

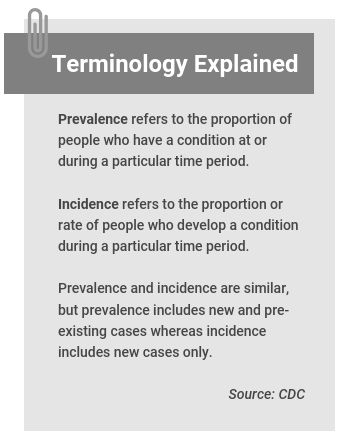

It said that the prevalence of mental illnesses among racial and ethnic minorities was similar to prevalence among white people, but also pointed out that most epidemiological studies were community household surveys and excluded vulnerable people who are homeless, incarcerated or in residential treatment centers, shelters and hospitals, where minorities tend to be overrepresented.

The report found that people of color had a greater burden of disability from mental illness — more likely to suffer from prolonged, chronic, and severely debilitating depression that affect their daily life — compared with whites because they often received less care and poorer quality care.

And it listed several barriers that deter people of color from accessing treatment, including mistrust and fear of treatment, racism and discrimination and differences in language.

In the two decades since little has changed.

“I’m sorry to say — and I’ve given a number of talks about this during the pandemic — those disparities are still with us,” says Dr. Enrique Neblett, Jr., professor of health behavior and health education at University of Michigan School of Public Health, whose research focuses on the impact of racism on health.

Overall, the country has failed to make significant progress toward reducing disparities in mental health care, Neblett says. One of the main reasons is persistent structural racism in the U.S.

“If you think about food insecurity, if you think about housing insecurity, if you think about the underinsured and unemployment, poverty, all of those things are clearly linked in studies to mental health outcomes,” he says. “How is access going to improve if there isn’t a concentrated, sustained structural investment in communities to improve the access to high quality care?”

In addition to structural racism leading to inferior care, being the target of racist behavior is linked to negative health outcomes.

Dr. Rebecca Brendel, the incoming president of the American Psychiatric Association, calls it a double whammy: “You have more stress, leading one to suffer negative mental health effects and it is harder to actually seek that help” because of institutional and structural racism, she says.

Other drivers of disparities

Disparities in mental health care, and in health care in general, refer to racial or ethnic differences in access to care and quality of care. It’s a definition used by the Institute of Medicine’s landmark 2003 report “Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care.”

Dr. Alfiee Breland-Noble, a mental health services researcher and founder of Aakoma Project, a nonprofit that aims to bring mental health awareness to young people of color, breaks down these disparities into three levels: individual, provider and historical.

At the individual level, cultural stigma around mental health care can prevent people from seeking care. Some studies have found that mental illness stigma tends to be higher among racial and ethnic minorities. In addition, some racial and ethnic groups may also have a different understanding of mental illness than white people.

“While in white communities often the thinking is that mental illness is medical and genetic, in many communities of color, it’s seen as a failure to thrive or it’s a failure to pray or it’s a personal flaw, or it’s just something that if you change your behaviors, you can get back,” Breland-Noble says.

When it comes provider disparities, people of color have a harder time finding a provider in their neighborhoods. Mental health providers who don’t take health insurance also tend to avoid establishing offices areas where people can’t pay the full price of the visit out of pocket, which means a dearth of providers in disproportionately disadvantaged, lower income communities, Neblett says. According to 2019 data from Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), 62% of psychiatrists accepted new patients with private insurance and Medicare, while 36% of them accepted new patients with Medicaid. In comparison, the overall rate of physicians accepting new Medicaid patients was 71%.

“The density of those high quality services is not the same across places and that pattern is driven by structural racism and residential segregation,” he adds. There are also disparities in treatment of mental illnesses, such as depression. For instance, with symptoms like anger, sadness, tearfulness and thoughts of death, young Black and Latino children are more likely to be diagnosed with conduct disorder or oppositional defiance disorder — while a white child with those symptoms will likely be diagnosed with depression, Breland-Noble says.

Some providers also have a perception that people of color aren’t going to take prescribed medications, so they don’t won’t offer it to them, “and that’s a disparity,” says Breland-Noble. “Because you’re not providing equitable care that is tied to what’s presenting in your office. You’re providing care based on your perception of what you think that patient is going to tolerate, sometimes without ever asking them.”

Meanwhile, there is a chronic shortage of providers of color in the U.S., in addition to the national shortage of mental health providers across the nation. As of 2019, 3% of more than 110,000 U.S. psychologists were Black, 7% were Hispanic. 4% Asian, 2% belonged to other races and ethnicities and 83% were white, according to the American Psychological Association. A 2020 study finds that in 2016 only 10% of 37,717 practicing psychiatrists were Black, Latino or Native American. “We must diversify, and we must train more diverse psychiatrists and other physicians,” says Brendel, who is also associate director of Center for Bioethics at Harvard Medical School.

People’s historical experiences with the mental health care system also plays a significant role in disparities, many times discouraging people of color from seeking care.

For instance, research has shown that women of color are less likely to seek care if they have postpartum depression compared with white women.

“Black women specifically are fearful of reporting symptoms of postpartum depression because they’re worried about their children being taken away from them,” says Breland-Noble.

Lack of diversity in mental health research is another issue. Racial and ethnic minorities continue to be underrepresented in clinical research. There’s also a need for more research into what treatments work best for communities of color, and more funding for researchers of color.

“We need a lot more work to establish treatments (medications and therapies) that are effective for racial and ethnic minority people,” says Neblett. “We want to make sure that the treatments that we think are effective, don’t cause further harm. And the only way to do that is to have people recruited and participate in the studies.”

Breland-Noble advocates for “practice-based evidence,” which refers to learning from people who are caring for patients and are engaged in communities, in order to build health practices based on what works.

Hope for the future

Despite lack of progress in recent decades, researchers are hopeful.

In March, President Biden announced a plan to address the nation’s mental health crisis. And more people are talking about mental health, a silver lining of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Breland-Noble is encouraged to see more organizations and initiatives like hers are focusing on helping people of colorand spreading ideas and practices that are helpful to different communities.

Her nonprofit is participating this week in the inaugural Mental Health Youth Action Forum in Washington, D.C., a collaboration between MTV Entertainment Group and the White House that aims to inform the development of creative mental health campaigns for at-risk communities.

“If you look over the arc of things, there have been periods of forward progress, and those periods of forward progress were often resisted,” says Neblett. “So, it’s a little bit of back and forth, back and forth. And we just have to keep pushing so that we can do what we can to promote health equity and improve the health of all Americans..”

Research roundup

Below is a collection of research to help you add data and context to your stories about disparities in mental health care. We’ve selected a wide range of studies to show the breadth of issues that arise from existing disparities. We’ve also included a few older studies because of their significance in the scope of mental health research on people of color.

How Does Use of Mental Health Care Vary by Demographics and Health Insurance Coverage?

Nirmita Panchal; et al. Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2022

Quick summary: The report, by the nonprofit policy organization Kaiser Family Foundation, explores how the use of mental health care varied across various populations, including racial and ethnic groups, before the pandemic, using data from the 2019 National Health Interview Survey, which is an annual household survey conducted by the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics. It finds among adults reporting moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety, depression, or both that mental health treatment rates were lowest among young adults, Black adults, men, and uninsured people. The report is a useful baseline for mental health disparities before the pandemic.

Highlight: Even though a similar percentage of white, Black and Hispanic adults reported moderate or severe symptoms of anxiety or depression, 53% of Black adults didn’t receive treatment, compared with 36% of white adults. Among Hispanic adults, 40% reported not receiving treatment. “Research suggests that structural inequities may contribute to disparities in use of mental health care, including lack of health insurance coverage and financial and logistical barriers to accessing care. Moreover, lack of a diverse mental health care workforce, the absence of culturally informed treatment options, and stereotypes and discrimination associated with poor mental health may also contribute to limited mental health treatment among Black adults,” the authors write.

Trends in Differences in Health Status and Health Care Access and Affordability by Race and Ethnicity in the United States, 1999-2018

Shiwani Mahajan; et al. JAMA, August 2021

Quick summary: The study analyzes National Health Interview Survey data from 1999 to 2018 to determine if the U.S. has made progress toward eliminating racial and ethnic disparities in physical and psychological health status and access. It finds that disparities persisted, although they improved for some groups. “The current study found that between 1999 and 2018, there had been no significant decrease in the percentage of people reporting poor or fair health across any racial and ethnic subgroup, and Black individuals consistently had the highest rates,” the authors write. There was no significant change in the difference in health status between Black and white individuals or between Latino/Hispanic and white individuals over the decades studied.

Highlight: Between 1999 and 2018, estimated rates of severe psychological distress significantly increased for Black, Latino/Hispanic and white individuals but there was no significant change for Asian individuals.

Trends in Suicide Rates by Race and Ethnicity in the United States

Rajeev Ramchand, Ph.D.; Joshua A. Gordon, M.D., Ph.D.; Jane L. Pearson, Ph.D. JAMA Network Open, May 2021

Quick summary: The study examines suicide rates among racial and ethnic minorities in the U.S. between 2018 and 2019. After adjusting for age, which is a statistical process that allows researchers to make fairer comparisons between different groups, suicide rates decreased for white and American Indian and Alaska Native individuals. Meanwhile, the rate for Black and Asian and Pacific Islander individuals increased between 2018 and 2019. Looking at a wider time range, the authors report that between 2014 and 2019, the suicide rate increased by 30% for Black individuals (from 5.7 to 7.4 per 100,000 individuals) and 16% for Asian or Pacific Islander individuals (from 6.1 to 7.1 per 100,000 individuals).

Highlight: “Although we will not be able to examine the association of COVID-19 with suicide rates for some time, recent reports suggest racial disparities in COVID-19 outcomes and suicide deaths in 1 state [Maryland] and the increase in Black and Asian or Pacific Islander youth suicide rates are worrisome,” the authors write. “Efforts are needed to mitigate suicide and its risk factors in population subgroups, which may include systemic and other factors that have placed increased stress on individuals who belong to racial/ethnic minority groups, particularly Black and Asian or Pacific Islander individuals.”

Coronavirus Trauma and African Americans’ Mental Health: Seizing Opportunities for Transformational Change

Lonnie R. Snowden and Jonathan M. Snowden. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, April 2021

Quick summary: The commentary, by Lonnie Snowden, professor of health policy and management at U.C. Berkeley, and Jonathan Snowden, an epidemiologist and assistance professor at Oregon Health & Science University’s School of Public Health, offers several recommendations to help reduce mental health care disparities affecting African Americans. “As illness places more African Americans at risk for psychological distress, so do higher death rates burden more African Americans with grief,” the authors write. “The system must restructure to better reach out to African Americans and provide newly required, culturally appropriate mental health assistance to an already underserved African American population.”

Highlight: “African Americans’ risk of COVID-related PTSD is compounded by high rates of previous trauma due to personal and family adversity,” the authors write. “African Americans are more likely to be victims of or witness violence and to have friends or relatives who become victims of violence. They also have experienced more traumatic childhood events, and levels of current PTSD are higher than whites. Previous trauma predicts responding to a new disaster with PTSD.”

Double Jeopardy: COVID-19 and Behavioral Health Disparities for Black and Latino Communities in the U.S.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020

Quick summary: This 5-page federal government report highlights the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people of color and spotlights existing disparities in access to behavioral health care. For instance, in 2020, it shows that 69% of Black and 67% of Hispanic adults with a mental illness received no treatment, compared with the national average of 56.7%. It calls for strategies that prevent disruption of substance use treatment and recovery services, increase capacity in telehealth and support for individuals with substance use disorder and serious mental illnesses who have COVID-19.

Highlight: The reports offers a series of potential solutions including policy efforts, communication and public awareness, community partnerships and augmenting health-care workforce with peer navigators, coaches and recovery support services. Some examples are expanded and flexible coverage for telehealth visits, timely translation of public health guidance to different languages, and identifying trusted messengers who can disseminate critical COVID-19 information.

Mental Health Issues in Racial and Ethnic Minority Elderly

Nhi-Ha T. Trinh, Richard Bernard-Negron and Iqbal “Ike” Ahmed. Current Psychiatry Reports, September 2019

Quick summary: This study evaluates the impact of race, ethnicity and culture on the aging process, psychopathology, psychiatric care, psychiatric education and clinical research. It also provides recommendations for future practices to improve care for this underserved population.

Highlight: “As the prevalence of dementia and other mental health disorders continues to grow for racial and ethnic minority elders, more efforts in pursuing research in general, and particularly designing and evaluating culturally tailored interventions, are needed to allow for earlier diagnosis, treatment, and education for racial and ethnic minority elders and their families,” the authors write. “By striving to better care for racial and ethnic minority elders, one of the most marginalized populations, health care is improved for all.”

Eliminating Mental Health Disparities by 2020: Everyone’s Actions Matter

Regina Bussing, M.D., Faye A. Gary, Ed.D., M.S., R.N. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, July 2012

Quick summary: The study addresses child and adolescent mental health disparities at the system level and patient level. The authors express concern with lack of patient diversity in research studies. “In an era that values evidence-based and personalized medicine, it is disconcerting that many psychiatric treatments lack generalizability to racial and ethnic minority populations.” The paper also highlights government initiatives aimed at eliminating disparities that were active when the study was published.

Highlight: “Youth from minority backgrounds who exhibit or are thought to exhibit behavioral or learning problems in school settings are less likely to receive high-quality mental health assessments and treatments,” the authors write. “Instead, they are more likely to be streamlined toward disciplinary responses, including detention and possible incarceration, with juvenile justice serving as the ‘de facto’ mental health treatment system for minority youth. Youth advocates are concerned that a ‘school-to-prison pipeline’ is fed by the increased use of the zero-tolerance discipline.”

Race and Unhealthy Behaviors: Chronic Stress, the HPA Axis, and Physical and Mental Health Disparities Over the Life Course

James S. Jackson, Ph.D., Katherine M. Knight, Ph.D., and Jane A. Rafferty. American Journal of Public Health, May 2010

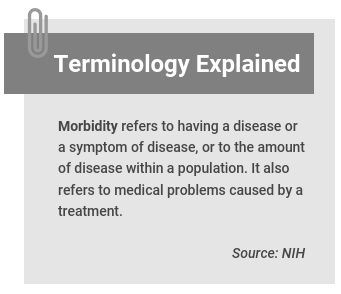

Quick summary: This study finds people who live in chronically stressful environments often cope by engaging in unhealthy behaviors, such as smoking, drinking, drug use or overeating comfort foods, actions that may have protective mental health effects. “However, such unhealthy behaviors can combine with negative environmental conditions to eventually contribute to morbidity and mortality disparities,” between Black and white populations, the authors write. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenalcortical (HPA) axis is one of the body’s biological systems that’s activated by stress. The authors believe that unhealthy behaviors may either block the neurologic cascade or mask the physiological and psychological experiences of poor mental health by acting on the HPA axis and related biological systems.

Highlight: The study is led by the late James Jackson, a social psychologist, who “changed the way scholars examined Black life in the United States,” according to his obituary in The New York Times. He founded the Program for Research on Black Americans at the University of Michigan in 1976 and later launched the National Survey of Black Americans, which was completed in 1980, according to the Times.

Prevalence and Distribution of Major Depressive Disorder in African Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and Non-Hispanic Whites: Results from the National Survey of American Life

David R. Williams; et al. JAMA Psychiatry, March 2007

Quick summary: When depression (major depressive disorder) affects African American and Caribbean Black individuals, it is usually untreated and is more severe and disabling compared with that in non-Hispanic white individuals. The research was one of the first psychiatric epidemiologic studies to include a large national sample of Black adults of Caribbean origin.

Highlight: “These findings also emphasize the need for the treatment of blacks with [Major Depressive Disorder],” the authors write. “In the United States, 57% of adults with MDD receive treatment, but we found that most blacks with MDD, irrespective of ethnicity, do not receive treatment. Only 48% of African Americans and 22% of Caribbean blacks with severe symptoms received treatment.”

Racist Incident–Based Trauma

Thema Bryant-Davis and Carlota Ocampo. The Counseling Psychologist, July 2005

Quick summary: This paper distinguishes traumatic stress from nontraumatic stress and draws parallels between experiences of racist incidents and other traumatic experiences such as rape or domestic violence. It groups mental health effects of racism into three categories, including direct consequences of institutional racism resulting in unequal access to mental health care; racist experiences that can have a negative impact on mental health; and internalization of stereotypes that lower one’s positive self-evaluation and well-being.

Highlight: The study is led by Thema Bryant, the incoming president-elect of the American Psychological Association.

Additional resources

- Anxiety and Depression. Data from U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, which began in April 2020 and is now in its third phase..

- How Does Use of Mental Health Care Vary by Demographics and Health Insurance Coverage? Nirmita Panchal; et al. Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2022.

- Racial/Ethnic Differences in Mental Health Service Use among Adults and Adolescents (2015-2019). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2021.

- Behavioral Health Equity Report 2021. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2021.

- Protecting Youth Mental Health. The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory, 2021.

- African American Youth Suicide: Report to Congress. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, October 2020.

- Ring the Alarm The Crisis of Black Youth Suicide in America. A Report to Congress from The Congressional Black Caucus, December 2019.

- How Discrimination in Health Care Affects Older Americans, and What Health Systems and Providers Can Do. Michelle M. Doty; et al. The Commonwealth Fund, April 2022.

- Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. SAMHSA, October 2021.

- Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Dr. David Satcher. Office of the Surgeon General, 1999.

- Words Matter: Reporting on Mental Health Conditions. American Psychiatric Association.

- “How bigotry created a black mental health crisis” Kylie M. Smith. The Washington Post, July 2019.

- “20 years ago, a landmark report spotlighted systemic racism in medicine. Why has so little changed?” Usha Lee McFarling. STAT, February 2022.

Experts

- Margarita Alegría, Ph.D., chief of the Disparities Research Unit at the Massachusetts General Hospital.

- Alfiee M. Breland-Noble, Ph.D., psychologist, scientist, author and founder of The AAKOMA Project, which also has a list of experts.

- Darrell Hudson, Ph.D., associate professor, Brown School at Washington University in St. Louis.

- Richard Lee, Ph.D., professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Minnesota.

- Enrique W. Neblett, Jr., Ph.D., professor, Health Behavior & Health Education; Faculty Co-Lead for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion; Associate director, Detroit Community-Academic Urban Research Center, University of Michigan.

- Wizdom A. Powell, Ph.D., M.P.H., Professor, director of UConn Health Disparities Institute.

The Journalist’s Resource is part of the Mental Health Parity Collaborative, a group of news organizations that are covering challenges and solutions to accessing mental health care in the U.S. The collaborators on this project include The Carter Center, The Center for Public Integrity, and newsrooms in Arizona, California, Georgia, Illinois, Pennsylvania and Texas.

Expert Commentary