The Minneapolis-based KARE 11 team’s months-long investigation into allegations of Medicaid fraud at several addiction recovery centers in Minnesota began with a tip, as many investigative stories do.

The tipster told the local TV station’s investigative team that there seemed to be problems in one specific area of addiction treatment called peer recovery services. There were rumors of Medicaid billing irregularities. Patients didn’t receive proper care.

Peer recovery services are provided by certified peer recovery specialists. KARE investigative reporter A.J. Lagoe explains the work of the specialists as kind of a mentor: someone who’s been down that road and is now walking along with someone newer in their addiction recovery journey.

“And it’s only been billable to Medicaid for a few years, but the program’s been exploding,” he says.

Medicaid is a joint federal and state program in the U.S. that provides health coverage primarily to eligible low-income adults, children, pregnant people, older adults and people with disabilities. Providers can bill Medicaid for a variety of services, including substance use treatment.

Through meticulous analysis of billing records, whistleblower accounts and insider documents, the KARE investigative team found alarming fraudulent practices at several recovery centers, including overbilling Medicaid for services never rendered and misrepresenting patient care.

The stories

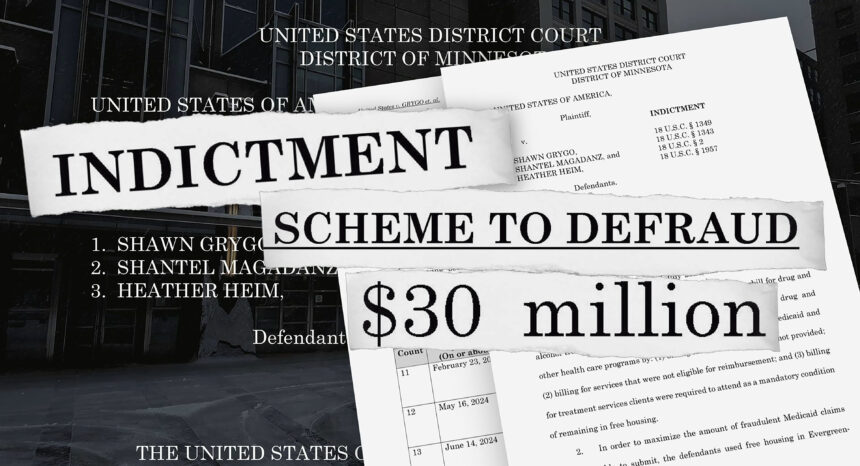

Led by Lagoe and investigative executive producer Steve Eckert, the KARE 11 Investigates team aired more than two dozen stories on the issue. Their work led to FBI investigations, resignations and criminal indictments.

The KARE investigations also prompted state-level legislative action, with bipartisan reforms aimed at preventing future abuses. Among the reforms passed:

- Increased peer supervision in addiction recovery centers. The new legislation requires peers have their work supervised by licensed alcohol and drug councilors or a mental health professional. Peers need to meet with their supervisors face-to-face at least once per month, review the recovery plans they have for clients and discuss ethical considerations, Lagoe explains.

- Enhanced bill auditing to ensure medical necessity of treatment.

- A ban on nonprofits with conflicting self-interests, to prevent the types of ties between nonprofit Refocus Recovery and the for-profit Kyros, which KARE investigation exposed.

- A requirement that addiction peer specialists be classified as employees, not as independent contractors.

KARE also successfully challenged an unconstitutional gag order placed on the station by a county judge, which Lagoe reported on.

The investigations focused on three Minnesota recovery centers: Kyros and Refocus Recovery, which were linked, and Evergreen Recovery.

KARE’s investigation revealed that the nonprofit Refocus Recovery billed Medicaid for peer recovery services and then funneled a substantial portion of those funds — over 96% of its revenue — to the for-profit Kyros, effectively channeling taxpayer dollars into the for-profit sector. Both the nonprofit and for-profit organizations were founded by the same person. In the wake of the investigation, the Minnesota Department of Human Services cited “a credible allegation of fraud” and halted payments to Refocus Recovery on September 6, 2024. Subsequently, Kyros ceased operations.

The team’s investigation into Evergreen Recovery unveiled extensive evidence of Medicaid fraud and unethical practices within the addiction treatment facility. The owners of the company used more than $10 million of the company’s funds for personal luxury expenses, including private jet charters. In a single month, the owners charged $440,742 to Louis Vuitton on the company’s credit line. Following the news station’s reports, the FBI raided the addiction treatment facility. Several top executives were indicted on fraud charges in December 2024.

The investigation also linked these systemic failures to real-world consequences, including a double murder where the perpetrator was falsely documented as receiving treatment at the time of committing the crime.

We spoke with Lagoe and Eckert about their investigative process. They shared 16 tips for reporting and producing an investigative series.

1. Vet tips with data and documents.

The KARE journalists didn’t take the initial tip at face value; instead, they sought Medicaid billing data.

“Our first step was to file open records requests with the state for billing data that we could then analyze,” Lagoe says.

“That quickly showed us that at least the basis of the tip — that this one new organization was drastically out-billing everybody else — was true,” he adds.

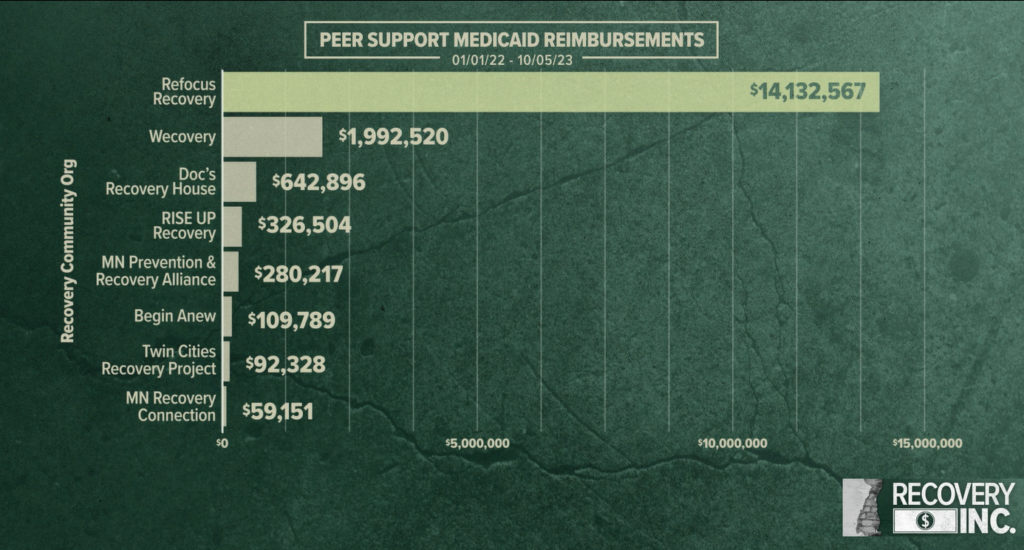

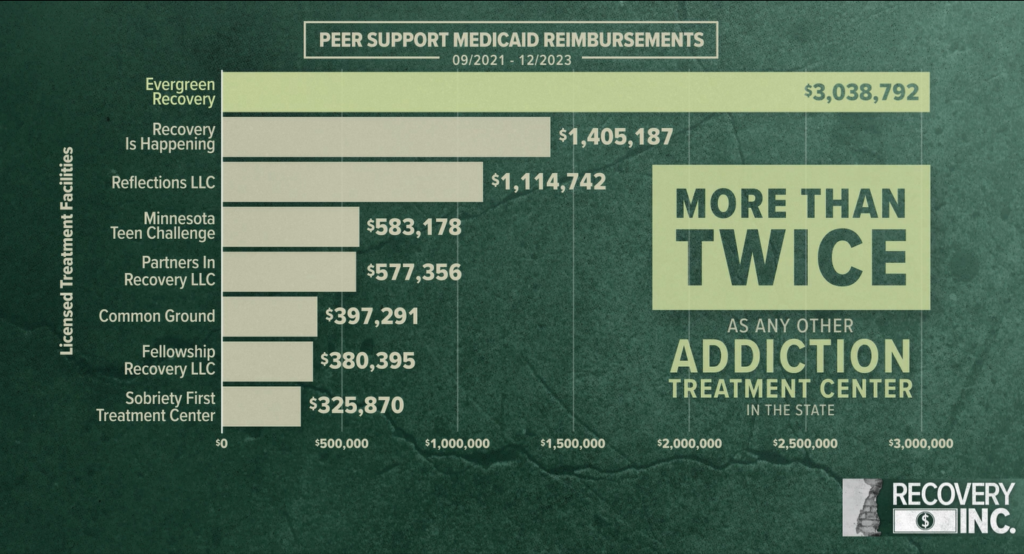

More specifically, they found that among the nonprofits that billed Medicaid for peer recovery services, Refocus Recovery far outbilled all others combined. Among licensed addiction treatment centers, Evergreen Recovery was billing more than twice any other center in the state.

2. Ask people in charge of the data for help crafting your open records request.

Every state has an agency that manages Medicaid. In Minnesota, it’s the Department of Human Services. At first, Lagoe reached out to the communications department to ask for the data.

“There was a lot of back and forth to get down to exactly what data we wanted and in a usable way,” Lagoe says. “We were just dealing with their PR staff and were not getting what we wanted.”

Eventually, KARE asked to speak with the people who handled the Medicaid data.

“It helped us craft our request and helped them respond and get us the data we were actually looking for in a way that we could analyze it,” Lagoe says.

Lagoe asked for all statewide Medicaid billing data for addiction services by billing code with a data key to explain the codes. The state website on billing peer services provides the codes for that subset of billing, Lagoe says.

3. Get to know the statutes and rules that govern what you’re investigating.

The statutes that govern peer services in Minnesota had a few requirements, Lagoe says. For instance, the laws say that peer support services had to be done one-on-one and not in a group setting. The peer had to have been a person in recovery for at least a year. For the phone calls to be billed to Medicaid, they had to have been scheduled ahead of time.

“Knowing these four or five key areas really let us become the experts to recognize when there was over-billing and false billing,” Lagoe says.

4. Get that first story out and keep pulling the string.

After seven months of dogged reporting, the KARE team aired its first story about Kyros, even though they knew their investigation wasn’t finished.

That story opened the floodgates, leading to more tips, information and documents. Whistleblowers contacted the team about potential false Medicaid billing at another facility, Evergreen Recovery.

The team eventually aired 14 reports on Kyros and Refocus Recovery, and 17 reports on Evergreen Recovery. They also created two specials, one on Kyros and Refocus Recovery, and another on Evergreen Recovery.

“In today’s fragmented media market, you can’t expect everyone to see a single report or two reports, but being on air or publishing on the web, story after story,” the public will eventually see it, Lagoe says.

Following the story over time also shows the power of being local journalists, Lagoe says.

“We’re not going away and we can keep chipping away as we find new details, and keep reporting on it and keep it in front of the public and the lawmakers to really drive reform,” he says.

5. Footnote everything.

The KARE investigative team is rigorous in adding a footnote to every statement of fact in the story script. They do so by simply adding an indented paragraph under each fact, and include reference documents, bios and websites. (In the TV and radio lingo, a script is the story or report journalists write.)

It helps the team “to not only make sure we’ve got the information right, but it serves as a valuable resource down the road if there are challenges to our reporting,” Eckert says.

6. Ask for documentation from sources to verify their claims.

The KARE team was meticulous in asking sources to provide documents to back up their claims.

In one case, a client told Lagoe that he was billed for treatments on days that he was delivering newspapers.

“And one of the ways he supported that claim was he had a paper route at the time, and he had saved Snapchat pictures of the route, date stamped,” Eckert says. Those dates matched the billing dates.

When a mom said she was at her son’s wedding on a day she was billed for a four-hour treatment session, she provided photos of that time and day dancing with her son during the reception.

“It’s requesting of your sources, ‘What documentation do you have? What information do you have that can support this claim?’” Eckert says.

Other helpful documents were text messages between employees and supervisors, and the patients’ medical and billing records.

“Our key findings in this investigation came down to clients being willing to get their treatment and billing records, which under law, the centers have to provide them,” Lagoe says.

7. Screen grab online information in case it disappears.

“Goodness gracious, screen grab darn near everything in terms of their websites and posts,” says Eckert, referring to people and companies you’re investigating.

For instance, one of the companies had instructions on their website for peer service providers, saying that they could bill for any call over eight minutes, while the state regulations said the exact opposite. There were two categories of phone calls the centers could legally bill for: emergency situations and pre-scheduled sessions.

“The day after we ran that story, they scrubbed their website,” Eckert says. “But we had screen grabs.”

The KARE team also had screen grabbed photos of key employees, which also disappeared from company websites after the stories began to air.

8. Document every interaction.

Lagoe keeps track of all his interactions and interviews in a spreadsheet. The name, email address, phone number, what the conversation was about, and any other information that might be useful.

It enables you “to go back and remember that two years ago I talked to this person who told me something at the time that didn’t make sense, and now is critically important,” Lagoe says.

9. Be transparent with sources to build trust.

Be patient when interviewing vulnerable people, many of whom have never had an interaction with journalists. Also, be upfront about expectations and promises, letting sources know that their story might never air.

“Explain the journalistic concepts and phrases that we use,” Lagoe advises. “Define how the information they share will be used, what’s on-the-record, what’s off-the-record, what’s on background, really talking it through with them.”

Explain why you’re asking for documents to back up the sources’ claims.

Lagoe asks his sources, “How do we bulletproof your story?” Or, “I’m helping you bulletproof your story, the facts you’re telling me, how can we do that?”

Lagoe talked with many clients whose stories didn’t air because he wasn’t able to fully document their claims.

“And we would tell them up front, ‘You have an important story here, but we need to be able to prove it. We need to be able to document this. We’re not just putting it out,’” he says.

“And I think taking the time and telling them that their story isn’t going to run until we have it bulletproof gave many of them a level of trust,” he says. It lets them know that “we weren’t looking to just quickly exploit them and move on.”

10. Hold off on interviewing sources on camera until you have all the documents.

Lagoe and the KARE investigative team arranged many coffee shop meetings and phone calls for background conversation with their sources, many times waiting for documents, before they turned on the camera.

11. Follow the money: when covering nonprofits, look for Form 990.

The Form 990 is a tax document that tax-exempt organizations, including nonprofits, must file annually with the Internal Revenue Service. It provides financial information about the organization’s revenue, expenses, assets, liabilities and compensation of key personnel.

Through the Form 990, the KARE team was able to show that the nonprofit Refocus Recovery billed Medicaid for peer recovery services and then funneled a substantial portion of these funds — over 96% of its revenue — to the for-profit Kyros.

The forms also documented that the for-profit and non-profit were founded by the same person, who also sat on the boards of both organizations.

“So there was a clear conflict, and we were able to document that through the 990s,” Eckert says.

ProPublica’s Nonprofit Explorer is a good source for nonprofits’ Form 990s.

12. Be ready for legal battles

In 2021, the KARE team had produced an investigative series about gaps in Minnesota’s criminal and mental health systems. As part of that series, they reported on a high-profile double-murder by a man named Joseph Sandoval, who had a history of severe mental illness. He was committed to the care of the state but then was released and sent to an outpatient treatment facility, where he killed two people.

That treatment facility was Evergreen Recovery, which Lagoe was now investigating for defrauding Medicaid by billing for services that were not provided.

Lagoe had a gut feeling that the double-murder case was somehow tied to the Medicaid billing irregularities at Evergreen. It would take months, but he would eventually connect the dots.

“It was like two of our big investigations had a baby,” Lagoe says.

But first came unexpected legal challenges.

Sandoval’s sentencing was in July 2024 and his defense attorney had filed a sentencing memorandum detailing significant lapses in mental health treatment leading up to the murders, information that was crucial to Lagoe’s reporting. Lagoe obtained the document from the court’s website.

The memo “documented a lot of what we were already looking into tied to Evergreen,” Lagoe says.

But then the county judge issued a gag order, barring Lagoe from reporting on the document. The judge said the memo was filed publicly in error.

The news station immediately filed an appeal, challenging the order as an unconstitutional prior restraint, a form of censorship where the government prevents the press from publishing information. The Minnesota Court of Appeals ultimately overturned the gag order.

“It was a case where the station was willing to take legal action to protect our right to report on a once publicly filed document,” Eckert says.

By November, using internal records from Evergreen, Lagoe was able to show that at the time Sandoval was six miles away committing the murders, the recovery center claimed that he was in a group treatment session and “appeared to participate in group.”

13. “Prime the pump” by proactively engaging with lawmakers and other key stakeholders before publishing.

“We don’t expect lawmakers to necessarily see our story on TV or read it,” Lagoe says.

So, he often meets with them on background shortly before the investigations air.

“[We tell them] we think there’s some stuff here that you guys could really work on fixing, and that gives them a little bit of ownership of the problem and makes it an issue to go fix,” Lagoe says.

“I call it ‘priming the pump,’ by giving a little heads up that this is what we’re going to do,” he says.

He then follows up with those lawmakers — Republican and Democrat — after the story runs, for an on-air response.

Given the limited on-air time for TV reports, it’s not possible to include all voices, including the lawmakers’, in every story. So instead, Lagoe uses those interviews to create follow-up stories and keep the issue on the front burner, he explains.

The reform to the peer recovery services was one of the only legislative actions during the last legislative session in Minnesota, Lagoe says.

14. Find reporting gaps with this simple question.

At various points throughout any of their investigations, the KARE team turns to this question: If we had to tell the story today, how would we tell it?

“That helps us identify videos that we’ll need, extra interviews and extra documentation that we don’t have yet,” Eckert says.

15. Advice for producers: Get involved early.

Eckert’s aim is to challenge the reporters to identify the weaknesses of a project.

“My theory is that killing bad stories quickly lets you spend more time on the really important and good stories, so we put a lot of emphasis on challenging reporters, initial tips, identifying questions we still need to answer early,” he says.

In a news station, a producer plays a central role in creating and coordinating news programs, shaping the broadcast’s content and structure.

In the context of KARE’s investigative unit, a producer acts as an off-air journalist who helps research and develop stories. They do data analysis, file FOIAs and conduct background research in advance of interviews. KARE’s executive producer does fact-checking and verification of the reports to ensure accuracy and fairness, Lagoe explains.

16. Advice for reporters: Keep your producer in the loop.

“Steve knows everything I’m working on and doing,” Lagoe says of Eckert. “It helps a lot that there are no surprises and at the end, he’s not reading a draft report and having all sorts of questions.”

Watch the reports

- The landing page for all the Recovery Inc. investigations.

- This 30-minute package, “Recovery, Inc.: The Rise and Fall of Kyros,” brings together KARE’s reporting on Kyros.

- The 30-minute package, “Recovery Inc.: The Evergreen Files,” brings together KARE’s reporting on Evergreen Recovery.

Expert Commentary