For journalists getting their feet wet covering U.S. nonprofits, the landscape can be daunting. What is a Form 990 and what can it tell you? What other documentation do nonprofits have to report to federal and state authorities? How are the wealthiest Americans increasingly deciding to contribute to charities?

“Holding nonprofits accountable is a lot like holding government agencies and corporations accountable,” Sundra Hominik, a senior editor at the Chronicle of Philanthropy, told The Journalist’s Resource by email. “You have to follow the money and ask, ‘How does what they’re doing make a difference in people’s lives?’”

We answer some of those questions below, with insights from Hominik, Mississippi Today investigative reporter Anna Wolfe and Ray Madoff, a Boston College law professor who studies philanthropic policy.

What is a nonprofit?

A nonprofit is an organization that does not seek to turn a profit to benefit owners or shareholders. Profit-making organizations, like Walmart or Amazon or a local attorney’s office, sell goods or services with the goal of taking in more money than it costs to offer those goods or services.

Instead of disbursing profits to owners or shareholders, nonprofits reinvest their earnings, which usually come by way of donations or investment returns, toward staff salaries, overhead costs like office leases, and funding programs or initiatives that advance their mission. Many nonprofits work toward an altruistic societal goal, such as ending poverty or offering after-school programs for kids.

Crucially, nonprofits are exempt from paying federal and state income taxes in nearly every state, provided the IRS has approved their status. All entities that are eligible for IRS tax-exemption are nonprofits that have applied for and received nonprofit status in their home state, according to the Arizona State University Lodestar Center for Philanthropy and Nonprofit Innovation.

There are a huge variety of nonprofits in terms of yearly gross receipts, staff size, salaries and mission. Many nonprofits bring in less than $1 million yearly and focus on addressing issues in a particular state, municipality or neighborhood. One of the biggest nonprofits headquartered in the U.S. is United Way Worldwide, which brought in more than $263 million in 2020, according to that year’s filing to the IRS.

There are five types of IRS tax-exempt organizations:

- Charitable organizations pursue goals generally expected to foster societal benefits. They are also called 501(c)(3) organizations, after the U.S. code that grants them tax-exempt status. Charitable organizations cannot be organized for the financial gain of the founder or anyone else, aside from job-related compensation. A charitable organization cannot try to influence legislation “as a substantial part of its activities,” according to the IRS, and it also cannot “participate in any campaign activity for or against political candidates.”

- Churches and religious organizations do not have to apply for tax exemption or file an annual Form 990, though officially receiving approval from the IRS assures contributors that their donations are tax-deductible. (More about Form 990s below.) Churches and religious organizations also fall under 501(c)(3).

- Private foundations are 501 (c)(3) organizations that usually have one source of funding, such as a family gift, and usually make grants to charities, rather than run programs themselves.

- Political organizations may include political action committees, political parties and campaign committees for candidates at all levels of government. Their tax exempt status is governed by U.S. code section 527.

- Other not-for-profit organizations, which may include civic clubs, business leagues and labor organizations. These organizations’ tax exempt status based on a variety of U.S. codes, depending on what they do.

If you are investigating a nonprofit, learn which types of information it must report to federal and state governments to maintain its nonprofit status. Federal reporting requirements for each type of nonprofit are available via the links in the list above, while states have separate requirements.

The IRS offers a searchable database of tax-exempt organizations here — by name, tax number and geography. Anyone can sign up for the IRS’ “Exempt Organizations Update,” an occasional e-mail newsletter with tax policy and other information for exempt organizations. The IRS also offers a free ten-part course that can help journalists understand rules and requirements for small-to-mid-sized nonprofits.

What is a Form 990 and where can you find it?

Under federal law, most nonprofits each year have to submit an IRS document called Form 990, Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax, reporting income, payouts for programs and other expenses, executive salaries and other information.

A nonprofit’s 990 shows where its money comes from and how it spends that money. It is a good source of information for journalists in the early stages of investigating a nonprofit — comparing 990s across years can yield further insights.

Tip: Look for sudden budget spikes. Wolfe, the Mississippi Today investigative reporter, recalls a nonprofit, the Mississippi Community Education Center, whose budget jumped from around $2 million yearly to tens of millions. Wolfe has spent years reporting on millions in federal grants that flowed through that nonprofit to Pro Football Hall of Famer Brett Favre and a pharmaceutical company he invested in.

Completed nonprofit tax forms are subject to public inspection, per federal law. Many journalists use Guidestar to access 990s submitted to the IRS. There is usually a lag of a year or more — the IRS notes it is still processing paper 990s filed in 2021 and later. Guidestar is free to use to pull up 990s, but requires registration and charges for advanced analytics.

Nonprofits will sometimes share more recent 990s with Guidestar than what is available through the IRS. For example, you can find United Way Worldwide’s 990 from 2020 via Guidestar; but their most recent 990 available from the IRS is from 2019.

ProPublica’s Nonprofit Explorer is another useful tool for finding and reviewing 990s. You can also go to nonprofits directly and ask for their most recent submitted 990. “If they won’t share it, that’s a sign,” says Wolfe.

As an example of what you can find in a 990, United Way Worldwide’s 2020 filing shows each of its top executives earned more than $250,000 in yearly salary, with the president and CEO earning more than $1.2 million in salary and other compensation.

Much of that organization’s top leadership has since turned over — a reminder that it’s important to verify that executives listed on the most recently available tax forms are still at the nonprofit.

Tip: Compare executive pay at one nonprofit to executive pay at other nonprofits with a similar size, structure and mission statement. Does executive pay at the nonprofit you’re investigating seem to be in line with or counter to the norm?

IRS reporting requirements for smaller nonprofits are a little different. Nonprofits that bring in less than $200,000 in a year and have less than $500,000 in total assets can use IRS Form 990-EZ, which is shorter and requires less detail than the full 990. Most nonprofits with yearly receipts under $50,000 can submit Form 990-N, which is entirely electronic and even shorter than the EZ form.

If a nonprofit makes over $1,000 yearly in business income unrelated to the charitable or educational reasons it received federal tax-exempt status, it has to pay federal taxes on that income — and submit an additional form, Form 990-T, to the IRS.

What can a Form 990 tell you?

Not everything, but a lot. They are a “good start,” according to Hominik, “but be prepared to do lots more legwork.” If an executive tells a journalist that their nonprofit is mostly privately funded but 990s show majority government funding, that’s a red flag, Wolfe says.

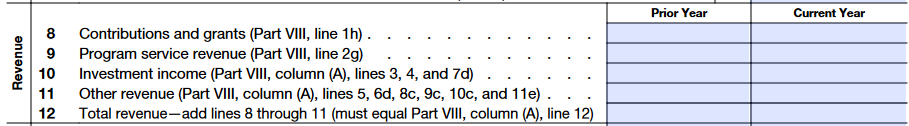

To find who is funding the nonprofit you’re covering, look at the “Revenue” rows of Part I:

Then, go to Part VIII to find more detail about the organization’s revenue:

You can also compare how much money is going toward administrative versus programmatic expenses. For example, a nonprofit that seeks to enhance career prospects for people with low income might fund and conduct programmatic expenses, such as resume building classes, as well as cover administrative expenses, such as staff salaries. Note that there may be valid reasons a nonprofit offers competitive executive salaries, particularly if those executives are adept at bringing in additional funding.

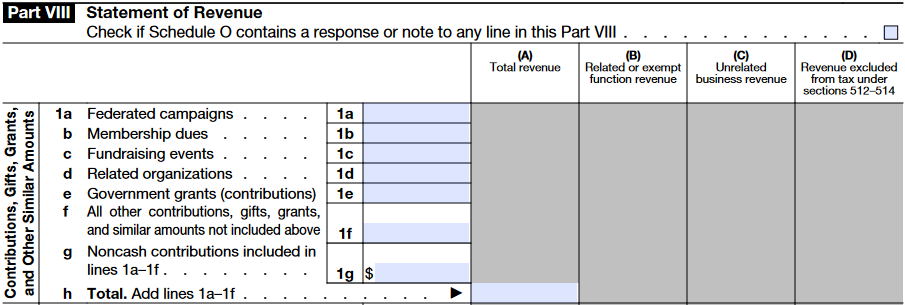

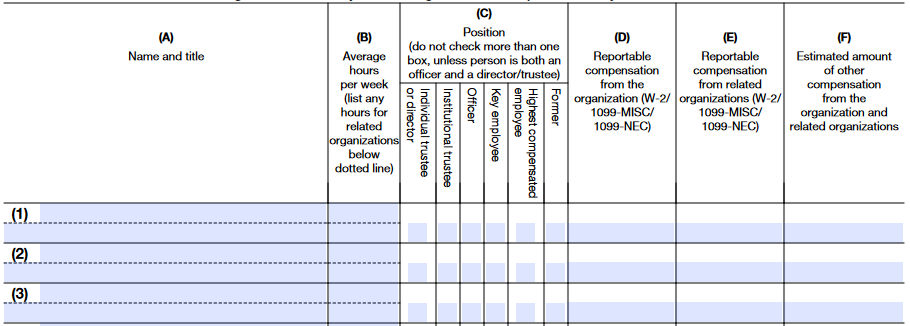

See the “Expenses” rows of Part I, then Part IX for details on administrative and programmatic expenses:

That said, there are nonprofits and other tax exempt organizations that don’t execute programs — private foundations, for example, usually fund other charities. As a rule of thumb, about 15% to 20% of a nonprofit’s income should go toward administrative expenses, Wolfe says.

990s are also good for understanding the organizational structure of a nonprofit and identifying members of its board of directors or governing board. Board members are usually responsible for ensuring the organization is operating in a financially responsible way. If you reach out to board members and they say they’re not getting regular financial reports, or meeting regularly, that’s another red flag, Wolfe says.

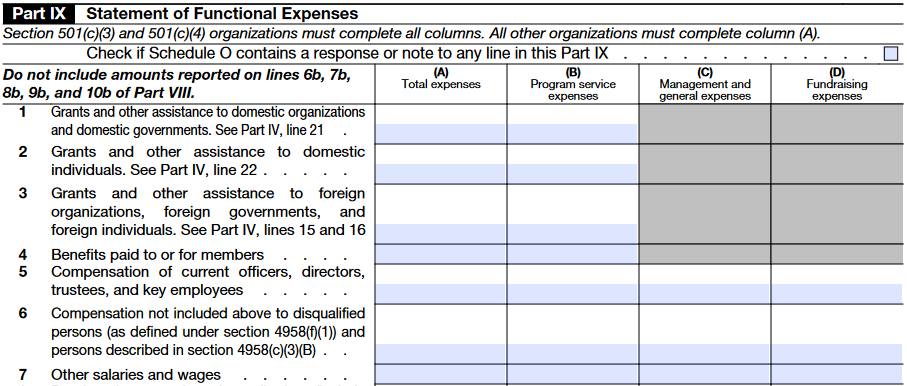

See part VII of a nonprofit’s 990 to find information on top officers and board members, including their names, titles, compensation and average weekly hours worked.

Where should journalists look beyond the 990?

If a nonprofit receives government grants of any type, “the state agency or granting body should have documentation, like invoices and expenditure reports, which I think is very exciting reporting but I don’t think a lot of people are doing it,” Wolfe says.

Tip: Note the type of grant a nonprofit receives — some grants may be more apt to be abused than others.

Reimbursements pay for work the nonprofit has already completed. Cash grants are upfront advances — intended to pay for programs down the road, and may indicate money being “pushed out of the door unchecked,” Wolfe says. Depending on the agency offering the grant, grant forms may have checkboxes indicating whether they are upfront advances or reimbursements, Wolfe says.

Federal and state government grants usually require that nonprofits send periodic progress reports to the granting agency that include details on how the money has been used and how people have been helped. If a nonprofit says they have seen positive outcomes from their programs, see if their reports to the government tell same story.

“As reporters, we can really only go on documentation,” Wolfe says.

What should journalists know about charitable contributions?

While government grants have reporting requirements that are publicly accessible, specific charitable contributions generally don’t — and it’s worth journalists’ time to understand how they have changed in recent years.

Tip: Be aware of charitable intermediaries, such as private foundations and donor advised funds, and how they operate.

Private foundations are nonprofits usually funded by a single family with the intention of using some of that money to provide charitable grants. Private foundations in the U.S. currently hold more than $1.3 trillion.

A donor advised fund is another type of 501(c)(3) nonprofit. Individuals or families establish accounts with these funds to dole out donations from cash or property contributions. Funds are managed by what the IRS calls a “sponsoring organization,” such as Fidelity Charitable, that is typically associated with a commercial financial institution. Account holders can use cash donations to a donor advised fund to write-off a large share of regular income taxes, with further tax benefits on interest the fund earns.

“In addition, [donor advised funds] afford donors anonymity that other forms of charitable giving may not permit,” write Madoff and co-author James Andreoni in a 2020 National Bureau of Economic Research working paper. “Donor advised funds are advantageous to DAF sponsors because sponsors receive management fees for the management of DAF assets. These fees can provide financial benefits for the financial institutions associated with commercial DAF sponsors and can play a significant role in supporting the work of community foundations and other mission driven DAF sponsors.”

Nearly one-third of charitable giving went through intermediaries in 2019, up from 18% in 2007, according to the Initiative to Accelerate Charitable Giving, which advocates for reform in the charitable giving industry. Madoff, the Boston College law professor, is a member of the initiative, along with nearly four dozen nonprofits, foundations and other philanthropic leaders.

“The problem is that there’s currently no requirement at all of any of these funds to be distributed to charity,” Madoff says. “Private foundations are required to spend 5% of their assets each year. If you have a $10 million foundation, it’s required to spend $500,000 a year. You can fully meet that $500,000 by paying salaries to your kids or having an annual trip to any favorite location and writing it off — or, giving to a donor-advised fund, which are not subject to any payout rules.”

Tip: Be skeptical of information financial intermediaries show the public. Donor advised funds, for example, often report overall payout rates across the accounts they manage. “That has nothing to do with individual accounts,” or how much money they manage or how much that money has grown over time, Madoff says. A small number of accounts may actually be distributing money to charitable causes, and making up most of the overall payout rate. The bulk of a fund’s accounts may not be making contributions.

“In practice, generally, funds remain in the [donor advised fund] account unless and until the donor recommends a grant,” write the authors of a March 2022 paper, featured below, which explores ethical issues related to donor advised funds. “The donor is under no obligation to make such recommendations.”

Recent research

Donor Advised Funds: Ethical Issues on the New Frontier of Philanthropy

James Biagi and Mark Hefter. Journal of Philanthropy and Marketing, March 2022.

The authors write: “It is widely alleged that DAF distributions are being used to pay the personal pledges of donor advisors, purchase gala tickets for donor advisors and their families, pay for private school tuition of donor advisors’ descendants, or donor advisor grant kickbacks, and the like. These uses are thought to be illegal as well as unethical, and critics cite such practices as a widespread abuse of DAFs.”

Board Chair-CEO Relationship, Board Chair Characteristics, and Nonprofit Executive Compensation

Nancy Chun Feng, Xiaoting Hao and Daniel Neely. Journal of Public and Nonprofit Affairs, February 2022.

The authors write: “Organizations with large boards and more revenues (and unrestricted cash) and those whose board chair and CEO have a cozy relationship should be diligent in ensuring that their CEO compensation-setting practices are well documented and reasonable and that they can be defended upon scrutiny.”

Analysis Suggests Government and Nonprofit Hospitals’ Charity Care Is Not Aligned With Their Favorable Tax Treatment

Ge Bai, et. al. Health Affairs, April 2021.

The authors write: “Using 2018 Medicare Hospital Cost Reports, we compared charity care provision across 1,024 government, 2,709 nonprofit, and 930 for-profit hospitals. In aggregate, nonprofit hospitals spent $2.3 of every $100 in total expenses incurred on charity care, which was less than government ($4.1) or for-profit ($3.8) hospitals.”

The Roots of the Gender Pay Gap for Nonprofit CEOs

Young-Joo Lee and Chang Kil Lee. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, March 2021.

The authors write: “Although women account for at least a half of the top leadership positions in the U.S. nonprofit sector, women CEOs are overrepresented in smaller, low budget organizations, and underrepresented in larger, high-budget organizations. The findings of this study reveal that this contrasting gender representation based on organizational size is at the root of the sector-wide gender pay gap for top executives.”

Calculating [Donor Advised Fund] Payout and What We Learn When We Do It Correctly

James Andreoni and Ray Madoff. National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, October 2020.

The authors write: “In the absence of account level reporting, the debate has focused on the average payout rates of DAF sponsoring organizations, which have been reported by the DAF industry to exceed 20%. We show that the industry-preferred method for calculating payout rate overstates the correct payout by more than 50%.”

Further reading

Former Gov. Phil Bryant Helped Brett Favre Secure Welfare Funding for USM Volleyball Stadium, Texts Reveal

Anna Wolfe. Mississippi Today, September 2022.

Whistleblowers Allege Embezzlement, Fraud at Tahlequah Nonprofit That Championed Indigenous Women

Whitney Bryen and Hannah France. Oklahoma Watch and KGOU public radio, August 2022.

Right-Wing Think Tank Family Research Council Is Now a Church in Eyes of the IRS

Andrea Suozzo. ProPublica, July 2022.

‘You Stuck Your Neck Out For Me’: Brett Favre used Fame and Favors to Pull Welfare Dollars

Anna Wolfe. Mississippi Today, April 2022.

The Conversation’s Coverage of Philanthropy and Nonprofits

Multiple authors, since November 2016.

Expert Commentary