Health misinformation is not a new phenomenon, but modern-day factors such as social media, in addition to politicization of health and science and the fast pace of scientific development during the pandemic have all made it easier for misinformation and disinformation to spread.

People who spread misinformation are not just fringe groups. Some politicians, public officials and a handful of physicians are now spreading misinformation. The growing trend highlights the increasingly important role of journalists in debunking misinformation, whether it’s presented at a press conference or as comments in an interview.

“In cases where public officials are spreading misinformation, the journalist’s responsibility is straightforward — either don’t report it; or report it while pointing out that it’s misinformation clearly, explicitly, and early, and telling people what the truth actually is,” Ed Yong, a Pulitzer Prize winning science journalist at The Atlantic, wrote in an email to The Journalist’s Resource. “I cannot stress enough that simply writing down what officials say is not journalism; you have to analyze, critique, and contextualize those comments, or you’re nothing more than an RSS feed with hands.”

The problem of misinformation has risen to a level that in November, the U.S. surgeon general issued a 22-page advisory titled “Confronting Health Misinformation,” dedicating a page to six tips for journalists and media organizations.

The report calls for training programs for journalists on how to recognize, correct and avoid amplifying misinformation. It also asks journalists to give more consideration to headlines and images they choose for their stories.

“If a headline is designed to fact-check a rumor, where possible, lead with the truth instead of simply repeating details of the rumor,” Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy recommends in the advisory. “Images are often shared on social media alongside headlines and can be easily manipulated and used out of context.”

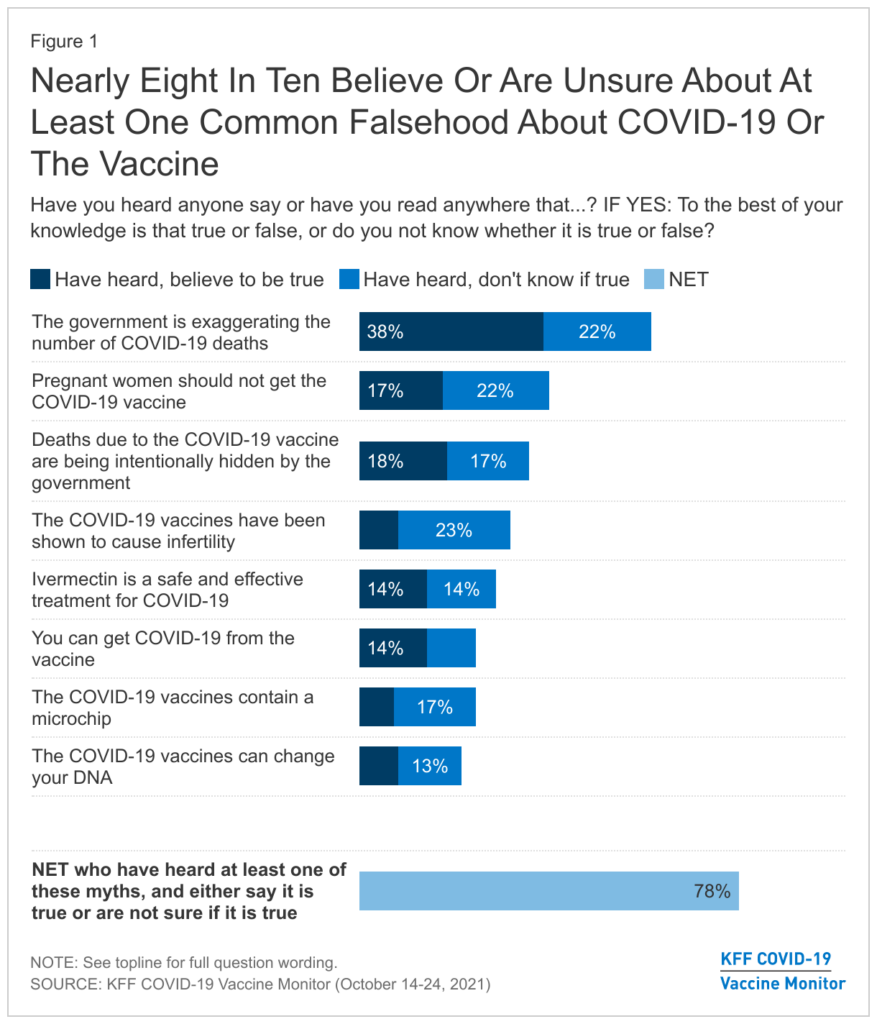

The Kaiser Family Foundation’s COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor report in November, focused on media and misinformation, shows how widespread is belief in pandemic-related misinformation. About 78% of the U.S. adults surveyed in October 2021 said they have heard at least one false statement about COVID-19 and that they believe it to be true or are unsure if it is true or false.

As a quick reminder, misinformation is information that is false, inaccurate or misleading according to the best available evidence at the time, regardless of intent to mislead. Disinformation is misinformation that is deliberately disseminated to mislead.

Brandy Zadrozny, a journalist and 2021-2022 research fellow at the Technology and Social Change Project at Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, who covers online extremism and disinformation, urges journalists to be brave and call disinformation what it is.

“I don’t think that we should sort of censor ourselves from facts because it’s a political issue and we don’t want to be seen as taking sides, when [in fact] there is one clear side,” she says.

In addition to Yong and Zadrozny, we spoke to several academics and researchers for advice on how to report on public officials and politicians who spread misinformation. Below are 7 tips gathered from those conversations.

Tip 1: Quickly correct the misinformation

If an official or politician is spreading misinformation, be quick to point it out. Instead of quoting them directly and amplifying it, provide the information that is correct, and report what the official has said is not grounded in evidence, advises Rebekah Nagler, a health communication researcher and an associate professor in the Hubbard School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Minnesota.

“I think that we can agree that the correction ought not to be buried way below the lead,” says Nagler. “Because that’s basically doing what we’ve seen in the social media space, where that information is allowed to sort of hang without immediate correction. And the longer that happens, we know those beliefs and perceptions can become more entrenched.”

You can also use the “truth sandwich” method: Start with the truth. Indicate the lie. Return to the truth. “Always repeat truths more than lies,” advises Roy Peter Clark of the Poynter Institute in a 2020 post.

Be quick to point out to your audiences when an official is speaking outside of the scientific consensus and contrary to proven data, advises Jessica Malaty Rivera, an infectious disease research fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital.

“There’s a responsibility here to say he said this and it’s wrong,” says Malaty Rivera.

Scientific consensus is when the majority of researchers and scientists in a field have reached an agreement based on the available scientific evidence. This tip sheet about scientific consensus has a list of resources to help you point your audience to documents that show scientific consensus.

I cannot stress enough that simply writing down what officials say is not journalism; you have to analyze, critique, and contextualize those comments, or you’re nothing more than an RSS feed with hands.

Ed Yong

This is how Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top infectious disease expert, responded to an unfounded claim made by a politician. In a recent interview, MSNBC host Joy Reid asked Fauci for comments about a false claim made by Republican Congressman Ronny Jackson, a physician from Texas, about the omicron variant.

“What do you say to somebody who is a doctor who is telling people publicly as a member of Congress that this is all made up, that this is all just an election strategy?” Reid asked.

Fauci replied: “I would just say without being pejorative against him that he is at odds in his feelings and his beliefs with virtually everybody who knows anything about virology, including the [World Health Organization] and all the other health ministers throughout the country and throughout the world.”

Be aware that sometimes, officials may not directly spread misinformation but raise questions about issues that are already backed by data and scientific consensus.

“Disinformation agents try to make a topic uncertain and debatable. … It may be settled science, such as measles vaccines,” says Dr. Wen-Ying Sylvia Chou, program director of the Health Communication and Informatics Research Branch at the National Cancer Institute. “But now it becomes debatable and that suddenly opens up the topic for all kinds of problems.”

Tip 2: Avoid false balance

Journalists often strive to be fair and objective, but in aiming to present both sides of an issues, they might end up creating “false balance” or “false equivalency,” which is “when one tries to treat two opposing positions as equally valid when they are simply not,” writes David Robert Grimes, a scientist and author, in his 2019 article “A dangerous balancing act,” published in EMBO Reports.

“If one position is supported by an abundance of evidence while another is entirely bereft of it, it is profoundly misguided to afford equal air‐time and coverage to both positions,” writes Grimes.

False balance is dangerous because it can amplify misinformation and lies and give them credibility. So even if the misinformation comes from a public official or politician, avoid giving it equal weight or credence. Instead, be quick to debunk the misinformation.

I don’t think that we should censor ourselves from facts because it’s a political issue and we don’t want to be seen as taking sides, when [in fact] there is one clear side. It’s the factual side of the overwhelming scientific community. We just have to be a little braver in reporting facts.

Brandy Zadrozny

Thomas Patterson, Bradlee Professor of Government and the Press at Harvard Kennedy School and one of the founders of The Journalist’s Resource, gave the following advice in a 2019 article: If one side is making erroneous claims or twisting the facts, journalists should say so in their coverage. Make it clear when claims are demonstrably untrue. Patterson says that a failure to do so increases the likelihood that the public will accept such claims as true.

In a 2016 article for the Association of Health Care Journalists, Tara Haelle writes that journalists “should only report scientifically outlier positions if solid evidence supports it, not just because someone is shouting it from their own tiny molehill.”

Also, if you’re quoting an official who’s spreading misinformation — for instance, that vaccines may not be safe — don’t call the scientific community, which overwhelmingly agrees that vaccines are safe, “critics.”

“It’s not just critics who are saying that,” says Zadrozny. “It’s the whole of public health. It’s the whole of science. What you have to do there is to say that the whole of public health disagrees and find the stance dangerous.”

Tip 3: Pick your words carefully for headlines and leads

“We have to be so discerning with what we choose to have in our headlines and what we choose to have in our leads,” says Malaty Rivera. “Because what often happens is logical fallacies. People will read a headline and assume total comprehension of a topic based on a handful of words. And that is most often the case when it comes to things like treatments or vaccines or events that cause something.”

Ask yourself what the audience will take away from your piece if they were to read just the headline, a tweet, a short post on social media or just the first few paragraphs of the article. Is there a conclusion that you don’t want them to come up with? “If the answer is maybe or yes, then rewrite it or get some scientists to give you feedback,” advises Malaty Rivera.

In “5 Lessons for Reporting in an Age of Disinformation,” Claire Wardle of First Draft, a nonprofit organization aiming to protect communities from harmful misinformation, writes: “It doesn’t matter if the 850 word article provides all the context and explanation to debunk or explain why a narrative or claim is false, if the 80 character version of that context is misleading, it’s all for nothing.”

Tip 4: Be leery of charts

Just because an official uses a chart or graph, it doesn’t mean that it’s an accurate one. Ask for the data behind it.

“At this point now, snake oil salespeople and people with bad intentions know how to sound scientific. So, they just science it up,” says Malaty Rivera. “People are very, very persuaded by data visualization, even if it’s bullshit. If it looks like a fancy chart with fancy color schemes and legends, people automatically assume that somebody smart made that. But you can put any number into an Excel spreadsheet, turn it into a graph and publish it and people [would say], ‘Oh, man, look at this research.’”

Tip 5: Be aware of the small group of physicians who spread misinformation

“Science is a very collaborative and evolving process,” says Malaty Rivera. “Many times, people say, ‘Well, I heard from this one doctor.’ and I’m like, OK, so one doctor is saying this one thing, when you have so many others with data to back it up saying something else. Think critically about that outlier.”

The American Medical Association’s House of Delegates adopted a policy in November to combat public health disinformation disseminated by health professionals, in all forms of media, and address disinformation that undermines public health initiatives. The association is also going to research disinformation disseminated by health professionals and its impact on public health and develop a comprehensive strategy to address it.

“Physicians are among the most trusted sources of information and advice for patients and the public at large, which is why it’s so dangerous when a physician or other health care professional spreads disinformation,” said AMA Board Member Dr. Jesse Ehrenfeld, in a news release.

The Center for Countering Digital Hate, an international nonprofit organization, which seeks to disrupt online hate and misinformation, has compiled a list of 12 doctors known for spreading disinformation with examples of how they are doing it.

Tip 6: Dig deeper into why an official or doctor is spreading misinformation

“Look at motivations and tactics used for spreading misinformation,” says Chou. “[Are they] using a topic and politicizing it or weaponizing it for political purposes? Sometimes there are financial incentives, or stoking fear. Fear mongering itself can be a powerful communication tool.”

Dig deeper to find out if the person has a business making money off a product they’re trying to peddle as an alternative to proven treatments or vaccines.

Zadronzy, who has reported on fringe doctor groups that have spread misinformation about COVID-19 and vaccines, suggests explaining why an official or physician’s statement is known to be false — and then exploring the motives of the fringe belief. “For instance, is there a financial or political motive?” Zadronzy says. “Say where the lie comes from and why you’re seeing it.”

Vet the people you talk to. It can be something as quick and simple as looking them up on Google or looking at their social media posts, advises Zadrozny.

Tip 7: Explain how misinformation and disinformation can lead to harm

“Misinformation damages society in a number of ways,” according to The Debunking Handbook 2020, written by a team of 22 scholars of misinformation, representing the current consensus on the science of debunking. “If parents withhold vaccinations from their children based on mistaken beliefs, public health suffers. If people fall for conspiracy theories surrounding COVID-19, they are less likely to comply with government guidelines to manage the pandemic, thereby imperiling all of us.”

Explain how people get COVID or are dying from it because they’ve come to believe that vaccines cause harm, or are turning to dangerous treatments, Zadrozny says.

“Don’t make the bad guys the centerpiece but [instead] people who are harmed,” she advises.

Additional reading

- Expert Tips for Digging Out the Roots of Disinformation. Maurice Oniang’o. Global Investigative Journalism Network, November 2021.

- It’s Not Misinformation. It’s Amplified Propaganda. Renée DiResta. The Atlantic, October 2021.

- 9 Ways to Know if Health Info Is Actually Junk Science. Timothy Caulfield. Men’s Health, October 2021.

- Five tactics used to spread vaccine misinformation in the wellness community, and why they work. Allyson Chiu and Razzan Nakhlawi. The Washington Post, October 2021.

- Misinformation online is bad in English. But it’s far worse in Spanish. Stephanie Valencia. The Washington Post, October 2021.

- The Swiss cheese model for mitigating online misinformation. Leticia Bode and Emily Vraga. Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, May 2021.

- Five rules for evidence communication. Michael Blastland; et al. Nature, November 2020

- 5 Lessons for Reporting in an Age of Disinformation. Claire Wardle. First Draft, December 2018.

- Covering scientific consensus: What to avoid and how to get it right. Denise-Marie Ordway. The Journalist’s Resource, November 2021

- Covering scientific consensus: What to avoid and how to get it right. Denise-Marie Ordway. The Journalist’s Resource. November 2021.

Resources

- The Debunking Handbook 2020 summarizes the current state of the science of misinformation and strategies for debunking it. It was written by a team of 22 scholars of misinformation and it represents the current consensus on the science of debunking for citizens, policymakers, journalists and other practitioners.

- First Draft is a nonprofit organization aiming to protect communities from harmful misinformation. Its Misinformation Monitor keeps track of the latest and most important misinformation narratives.

- Center for Countering Digital Hate, an international nonprofit organization, with offices in London and Washington, D.C., seeks to disrupt online hate and misinformation. One of the center’s recent reports is “Pandemic Profiteers: The business of anti-vaxx.”

- Harvard Kennedy School’s Misinformation Review is a peer-reviewed publication with content produced by misinformation scientists and scholars and geared toward real-world implications.

- The Media Manipulation Casebook is a digital research platform and a resource for researchers, journalists, educators and others who want to learn about detecting, documenting, describing and debunking misinformation, disinformation and media manipulation.

Our interview sources

- Dr. Wen-Ying Sylvia Chou, program director of the Health Communication and Informatics Research Branch at the National Cancer Institute.

- Jessica Malaty Rivera; infectious disease research fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital. Malaty Rivera has a strong following on social media, where she answers questions via her Instagram stories and helps dispel misinformation.

- Rebekah Nagler, a health communication researcher and Beverly and Richard Fink Professor in Liberal Arts and an associate professor at the Hubbard School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Minnesota, and co-author of the 2020 study “The Emergence of COVID-19 in the US: A Public Health and Political Communication Crisis,” published in the Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law.

- Sarah Gollust, associate professor at the Division of Health Policy and Management at the University of Minnesota and co-author of 2020 study “The Emergence of COVID-19 in the US: A Public Health and Political Communication Crisis.”

- Jennifer Nilsen, a research fellow at the Technology and Social Change Project at the Shorenstein Center, who researches misinformation and has worked on the Media Manipulation Casebook. Her latest publication is “Ebola and the U.S. Border: Spreading Virus Rumors to Build the Wall.”

- Brandy Zadrozny, a journalist and 2021-2022 research fellow at the Technology and Social Change Project at the Shorenstein Center.

- Ed Yong, a Pulitzer Prize-winning science journalist at The Atlantic.

Expert Commentary