Unlocked is a new series focused on explaining U.S. federal government systems, structures, and processes. This Medicaid explainer is part of that series, which is produced by The Journalist’s Resource and the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, where JR is housed.

In 2005, Missouri faced a budget crisis stemming from a national recession that had stretched through much of 2001. To address its budget crunch, the state decided to make sweeping cuts to Medicaid, a government program that provides health coverage for millions of low-income people.

The cuts were meant to help Missouri balance its budget, but instead, they disrupted health coverage for people in need and took a financial toll on providers who cared for them, according to a 2009 study published in the journal Health Affairs.

More than 100,000 people lost Medicaid coverage; 370,000 more who didn’t lose their coverage faced reduced benefits — they lost coverage for things like eye doctor visits, eyeglasses, wheelchairs and prosthetics.

The number of uninsured people grew. Medicaid revenue fell for community health centers that act as the safety net for low-income people.

“[T]he burden of uncompensated care on hospitals grew, and clinics were forced to seek additional sources of grant revenue and raise patient fees,” the study authors write.

Meanwhile, the state’s Medicaid spending growth slowed in the two years after the 2005 cuts, from 11% each year to less than 4%, but it did not fall, the study found.

Two decades later, talks about potential cuts to the Medicaid program are in the headlines, this time at a national level and at a much larger scale. In this research-based explainer, we focus on some of the Medicaid policies that may be subject to cuts and provide journalists with fact-based background information, resources and research to help with their reporting in the coming weeks and months.

- Medicaid basics

- Medicaid by the numbers

- How the federal-state match program works

- What happens if the 90% federal match rate for ACA Medicaid expansion is reduced?

- What are Medicaid provider taxes?

- How big of a problem are fraud, waste and abuse in Medicaid?

- What are Medicaid work requirements?

- What are block grants and per capita caps?

- A few research studies to help with your reporting

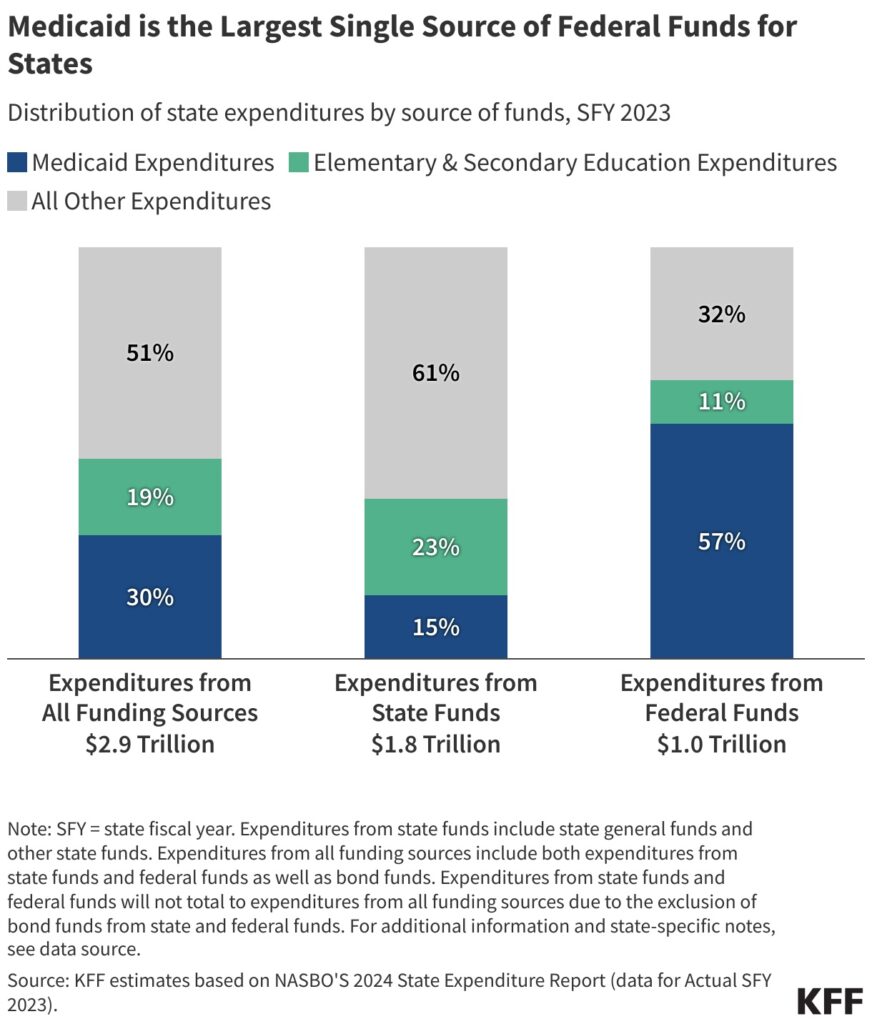

Medicaid is jointly funded by states and the federal government and provides health coverage to one in five Americans with low income, including adults, children, pregnant women, older adults and people with disabilities. It’s a major source of federal funding for states, and it makes up a large part of state budgets, after elementary and secondary education.

The budget framework passed by Congressional Republicans in both chambers in early April requires the House Committee on Energy and Commerce to cut at least $880 billion in federal spending over the next 10 years to help finance $4.5 trillion in tax cuts. Although the resolution doesn’t mandate cuts to Medicaid, the program makes up about 93% of non-Medicare funding that the committee oversees, making it the main target for cuts. The Energy and Commerce Committee has sole jurisdiction over Medicaid in the House. In the Senate, the Finance Committee oversees the program, according to KFF. (Medicare is a federal health insurance program for nearly 68.5 million people 65 or older and some people with disabilities. About 12.5 million are covered by both Medicare and Medicaid, also referred to as dual-eligibles. Medicare is overseen by the Ways and Means Committee and the Energy and Commerce Committee in the House. In the Senate, the Finance Committee oversees the program.)

Medicaid remains a popular program. The majority of Americans want to maintain or increase Medicaid funding, according to a March survey of 1,300 adults by the non-partisan health policy organization KFF. Only 17% said they supported a decrease in Medicaid funding.

At the time of publication of this piece, it’s unclear how Republican lawmakers are going to cut Medicaid, but some of the policy options that have been discussed include requiring adults to have jobs to get Medicaid coverage, capping Medicaid funding for states, restricting how much states can collect in provider taxes, reducing the amount of federal money states currently receive for expanding Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, and curbing fraud, waste and abuse.

Conservative policy think tanks like The Heritage Foundation say that after nearly 6 decades, the program needs reform. But other Medicaid experts say that the cuts, even if they target fraud and not coverage levels, are bound to squeeze state budgets and impact people.

The cuts at such a scale are “hugely consequential for the many vulnerable populations who rely on Medicaid for health care,” says Joan Alker, executive director of Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families and a prominent researcher on Medicaid policy, in an interview with The Journalist’s Resource.

According to a March analysis by KFF, if the $880 billion cuts over 10 years were allocated across the states evenly — $88 billion in cuts per year — Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan and Minnesota would each lose $2 billion in Medicaid funding per year. Florida would lose $4 billion and Texas $6 billion.

States would have to increase their share of Medicaid spending by 29%, cut their Medicaid programs, or they “would need to increase state revenue or taxes per person by about 6% or decrease education spending per pupil by nearly one-fifth,” said Robin Rudowitz, vice president and director for Program on Medicaid and Uninsured during a March 23 online briefing. “These are hard decisions that states would be faced with, with limited ability to use federal dollars.”

House and Senate committees have indicated that they plan to draft final legislation and get it to the president by Memorial Day. The House Energy and Commerce Committee is planning on meeting on May 7, The Hill reported on April 29.

Now is a good time for local journalists to reach out to their governors and state lawmakers to find out what they think of proposed cuts to Medicaid, advised Alice Miranda Ollstein, a senior health care reporter for POLITICO, during an online briefing hosted by USC Center of Health Journalism on April 23.

“Are they reaching out to their federal counterparts and if so, what are they telling them?” she asked. “I think reporters should be really drilling down on what exactly [state governors] would and wouldn’t be OK with,” in the context of Medicaid cuts.

Ollstein also encouraged journalists to reach out to hospitals and hospital associations, which are very concerned about how Medicaid cuts could affect their bottom lines.

“Are they mobilizing? Are they lobbying? Are they putting pressure on the folks in power?” Ollstein asked.

Journalists should also explain how critical Medicaid coverage is to individuals and how complex it is for people to navigate, said Celia Valdez, health outreach and navigation director with Maternal and Child Health Access, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit, during the Center for Health Journalism’s April 23 webinar.

Medicaid basics

Medicaid was signed into law in 1965 as a health insurance program for low-income people. As of November 2024, nearly 72 million people were enrolled in Medicaid in the 50 states and the District of Columbia, according to medicaid.gov.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in the Department of Health and Human Services administers Medicaid and oversees state programs.

The Children’s Health Insurance Program, or CHIP, is an affiliated Medicaid program that covers children in families with incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid, but too low to afford private insurance. CHIP was signed into law in 1997. As of November 2024, 7.3 million children were enrolled in CHIP. It’s not clear whether cuts to CHIP are also on the table.

Medicaid is jointly financed by states and the federal government. The federal government sets broad rules for the program, but each state administers its own Medicaid program, with some flexibility to decide what populations and services to cover, how to deliver care and how much to reimburse providers, according to KFF.

In exchange for receiving federal funds, states must meet minimum federal standards for care. States also must cover Medicaid’s core population of low-income pregnant women, children, people with disabilities and low-income people 65 years and older without waiting lists or limits to the number of enrollees.

States can obtain what’s called Section 1115 waivers to test and implement approaches different from what’s required by federal statute. The Health and Human Services Secretary determines if the waiver would promote the objectives of Medicaid, according to KFF. Almost all states have at least one active Section 1115 waiver. For instance, several states have a waiver that provides limited health services, such as case management and wellness exams, for people leaving incarceration. Work requirements are another example.

Resources

- See this KFF page for state-by-state Medicaid fact sheets.

- KFF has a comprehensive primer on Medicaid, including how Medicaid is financed, who is covered by Medicaid and how much Medicaid spends on what.

- The National Conference of State Legislatures also has a comprehensive Medicaid Toolkit.

- KFF has a Section 1115 waiver tracker by state.

- Watch this April 2025 webinar on Medicaid’s effects on mental and physical health and financial well-being, hosted by Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families.

Medicaid by the numbers

Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid are the three biggest entitlement programs in the U.S. Together, they make up 41% of the money the U.S. government spends each year. Medicaid and CHIP are the smallest of the three in terms of federal spending, but the program covers more people than Medicare or Social Security, according to KFF.

Medicaid accounts for about $1 out of every $5 spent on health care in the U.S. Medicaid spending was about $880 billion in 2023. The federal government paid 69% of that total and states paid 31%.

For states, Medicaid is both a spending item and a major source of federal funding. In 2023, 57% of all the federal funds sent to states went toward paying for Medicaid, while 15% of all state funding went toward Medicaid, highlighting the importance of federal funding for the program. In states, elementary and secondary education are the largest source of spending at 23%, according to KFF.

Medicaid is “probably the cheapest form of health insurance we have in the United States,” said Timothy Layton, associate professor of public policy and economics at the University of Virginia, during a March 13 online briefing hosted by SciLine. “Medicaid pays much lower rates to providers than anyone else.”

Medicaid is the single largest payer for births, mental health services and long-term services, said Megan Cole, associate professor of health law, policy and management at the Boston University School of Public Health, during the SciLine briefing.

In 2023, Medicaid covered 39% of children up to 18 years; 80% of children in poverty; 16.5% of adults between 19 and 64 years; and 60% of adults under 65 who lived in poverty, according to KFF, which also provides state-level data.

Medicaid also provides health coverage to 44% of non-elderly adults with disabilities who are not in a hospital or long-term facility.

Medicaid spending is driven by factors such as the number and mix of enrollees, their use of services, the price of Medicaid services and state Medicaid benefits and provider payment rates, according to KFF.

Low-income adults 65 years and older and people with disabilities make up about a quarter of Medicaid enrollees but account for more than half of total Medicaid spending, because of high health needs. Children account for a third of enrollees, but only 14% of spending. Low-income adults, and those eligible under the ACA Medicaid expansion, account for 43% of enrollees and 34% of spending, according to KFF.

Medicaid and CHIP enrollees are more racially diverse compared with the U.S. population.

In 2023, 39.5% of Medicaid enrollees under age 65 were white; 18.5% were Black; 29.9% were Hispanic; 4.7% were Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander; 1% were American Indian or Alaska Native; and 6.5% were of multiple races, according to KFF. This means about 60% of Medicaid enrollees are from racial and ethnic minority groups, and potential cuts to Medicaid can disproportionately impact them and widen existing health disparities.

In rural communities, residents and hospitals disproportionately rely on Medicaid.

Medicaid covers nearly 20% of adults and 40% of children in rural areas, according to the National Rural Health Association. Nearly half of rural hospitals operate with negative margins and cuts to Medicaid could force them to reduce essential services, delay upgrades, or close their doors altogether.

Resources

- KFF tracks state-level Medicaid and CHIP enrollment data.

- CMS’s Medicaid Enrollment Snapshot has the latest available Medicaid data.

- Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families has several useful datasets, including Medicaid and CHIP coverage by congressional district, Medicaid coverage in metro and small towns and rural counties and state-by-state Medicaid snapshot.

- Watch SciLine’s media briefing on the potential impacts of proposed Medicaid cuts.

- Watch the April 23 webinar about the future of Medicaid hosted by USC Annenberg’s Center for Health Journalism.

- Read this January 2025 report on Medicaid’s role in small towns and rural areas by Georgetown University Center for Children and Families.

- Learn five key facts about Medicaid and hospitals with this March 2025 report by KFF.

- And this March 2025 report by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation on hospital revenue losses if Medicaid funding is cut.

- KFF provides a look at variation in Medicaid spending per enrollee across states.

- Read this May 2025 explainer by the Commonwealth Fund on how Medicaid benefits states.

How does the federal-state match program work?

Medicaid is jointly funded by states and the federal government through a federal match program known as the federal medical assistance percentage, or FMAP. The percentage of Medicaid costs that the federal government pays varies by state, based on the states’ per capita income relative to the national average. The federal government provides a match rate of at least 50% to states. This rate goes up for states with lower per capita income, according to KFF. For the 2026 federal fiscal year, Mississippi received the highest match rate of 77%.

FMAP cannot be lower than 50% or exceed 83%.

Certain Medicaid services receive enhanced FMAP rates. For instance, CHIP and coverage provided through the ACA Medicaid expansion have higher federal match rates, according to an April 2025 report by the Congressional Research Service. The federal government pays states that have expanded Medicaid a 90% match rate for the cost of expansion, while the states pay 10%.

Also, temporary adjustments to FMAP have been enacted during economic downturns or public health emergencies to provide states with increased federal support.

FMAP significantly influences state budgets, as Medicaid is a major expenditure for states, according to the Congressional Research Service’s report. A higher FMAP means more federal funds and less state spending, allowing states to allocate resources to other areas. Conversely, a lower FMAP increases the financial burden on states.

States determine how to finance the non-federal share of the state Medicaid payments. States appropriate their general funds directly to Medicaid. They also use funding from local governments or revenue from provider taxes and fees, according to KFF.

Resources

- KFF has a Medicaid financing primer.

- The U.S. Government Accountability Office has a primer on Medicaid financing.

- This Congressional Research Services report explains FMAP in detail.

- This KFF list shows the FMAP rates by state.

What happens if the 90% federal match rate for ACA Medicaid expansion is reduced?

In 2010, the Affordable Care Act expanded Medicaid to almost all adults under age 65 with income up to 138% of the federal poverty guidelines, or $21,597 yearly income for one person in 2025. So far, 41 states have expanded Medicaid. ACA Medicaid expansion currently covers more than 20 million people, according to KFF. A Supreme Court ruling in 2012 made expansion optional for states.

States that have expanded Medicaid coverage receive a 90% federal match rate, meaning that the federal government pays 90% of the costs of enrollees. The match rate was established to incentivize states to expand Medicaid coverage to more low-income people.

Republican lawmakers have indicated they are considering reducing the 90% FMAP for states that have expanded Medicaid. This would shift more of the cost to states. Ideally, no one would lose coverage if states had the budget to step in to fill the gap, but that’s unlikely, according to experts.

“That would end the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion as we know it, ending coverage for millions of people,” says Alker of Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families.

Eliminating the enhanced federal match rate could reduce Medicaid spending by $1.9 trillion over 10 years, but many would lose their Medicaid coverage, according to a February 2025 KFF analysis.

The analysis offers two potential scenarios resulting from reduced match rates.

In one scenario, if all states that have expanded Medicaid pick up the new costs, that would mean an additional $626 billion in state spending over a 10-year period across all states.

To offset the loss of federal funding, states would have to increase general taxes or reduce spending on other services, such as education, which is the largest source of spending from state funds. States could also decrease Medicaid coverage for some groups, eliminate optional Medicaid benefits such as prescription drugs, or reduce payment rates to providers.

In another scenario, if the states that have expanded Medicaid dropped expansion altogether, there would be $186 billion cut to state Medicaid spending across all states, including non-expansion states. In total, federal and state Medicaid spending would decrease by $1.9 trillion over 10 years. However, nearly 20 million would lose their Medicaid coverage, according to KFF.

Under the last scenario, some people who lose expansion coverage could qualify for Medicaid through other pathways, such as disability, or become eligible for coverage through the ACA marketplace, but many could become uninsured, according to the analysis.

Resources

- This RWJF June 2025 analysis calculates the impact on states if FMAP floor of 50% is reduced.

- KFF provides a list of key facts about the uninsured U.S. population.

- Read KFF’s five key facts about Medicaid expansion.

- A list of studies about the effects of Medicaid expansion.

- KFF’s state-by-state estimates if the federal Medicaid expansion match rate is eliminated.

- See this May 2020 Commonwealth Fund report on the impact of Medicaid expansion on states’ budgets.

- See Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families’ November 2024 report on how covering adults through Medicaid expansion helps children.

What are Medicaid provider taxes?

Provider taxes are fees or taxes that states charge hospitals, nursing homes, facilities that care for people with developmental disabilities and others, including ambulatory care and home care providers. The maximum allowable amount of provider tax is 6% of a provider’s net patient revenue. Most states finance a portion of their Medicaid spending through taxes on health care providers. All states, except for Alaska, have provider taxes.

Since the early 1990s, a set of statutory and regulatory provisions has allowed the states to use provider taxes as one source of revenue to pay their share of Medicaid, explained Andy Schneider, a research professor at the Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Health, during the April 23 briefing hosted by Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families.

One option under Congress’ consideration for Medicaid cuts is to limit or eliminate the use of provider taxes on providers. If provider taxes were eliminated, federal spending would decrease $612 billion over 10 years, according to a 2024 analysis by the Congressional Budget Office.

Proponents of cutting provider taxes, including the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, say that states use the provider tax revenue “to remit payments back to providers, reporting the payments to the federal government in the process to collect matching funds,” hence inflating the state’s Medicaid match.

But other policy experts disagree. Reducing state provider taxes doesn’t directly affect the federal match rate for Medicaid. Rather, “it’s really about changing what states can do to raise their share of the cost of Medicaid,” said Edwin Park, a research professor at Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families, during the April 23 briefing.

Reducing provider tax revenue for states can reduce federal spending “because they assume states won’t be able to replace these revenues,” Park said. As a result of a reduction in revenues, the states might change their behavior, such as dropping Medicaid expansion, which is optional for states, or cut payments to providers.

“I describe it like a balloon pushing,” said Robin Rudowitz, vice president and director for the Program on Medicaid and Uninsured during the briefing. “If you’re cutting something here, you’re going to push part of the balloon and need to finance it some other way, or the services or access is going to go away.”

Both proponents and detractors agree that there’s limited data about provider taxes, which makes it difficult to “assess states’ reliance on them as a funding source and to understand how they affect net payments to providers,” according to a March report by KFF.

Resources

- Get in the weeds of provider taxes with this webinar hosted by Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families.

- See this helpful explainer about Medicaid provider taxes by Georgetown University’s Center for Children’s and Families.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office has a primer on state Medicaid financing.

- KFF’s five key facts about Medicaid and provider taxes is a detailed overview of the issue.

federal funds. (Source: GAO 2020 report, “Medicaid: Primer on Financing Arrangements.”)

How big of a problem are fraud, waste and abuse in Medicaid?

Another option that Congressional Republicans have suggested for cutting Medicaid is targeting fraud, waste and abuse in the program.

There’s no reliable measure for the amount of fraud in Medicaid. While a new report by the conservative think tank Paragon Health Institute estimates that Medicaid made nearly $1.1 trillion in improper payments in the past 10 years, other policy experts have disputed the findings, saying that the numbers used in the Paragon report are improper payments to providers, most of which are not fraud.

To be sure, fraud, waste and abuse are not unique to Medicaid and affect other parts of the health care system, including other forms of health coverage, such as Medicare and private insurance. And the terms, although often conflated, have different meanings.

“Fraud is all about intent,” said Timothy Hill, senior vice president of health at the American Institute for Research, during a briefing about Medicaid fraud hosted by KFF on April 24. “It’s when someone knowingly takes a false action or creates a deception to gain unauthorized benefits.”

It’s billing for services that aren’t provided or charging for medical services and equipment that were never delivered, said Christi Grimm, former inspector general at HHS, during the KFF briefing.

Medicaid fraud is considered a criminal act.

The financial impact of fraud is challenging to detect, “because it is an act of deception,” Grimm said. “We don’t have a terrific estimate, but we know from our Medicaid Fraud Control Units that operate in each state and some territories, it is at least a billion dollars annually.”

Abuse is “sort of on the road to fraud,” Hill explained. “It’s not as clear-cut. There’s no intent. It’s someone taking advantage of perhaps unclear billing rules or confusing guidance to maximize payment or revenue.”

Hill said he thinks of waste “as a policy issue, as opposed to an issue that affects individual transactions. It’s about the misuse of resources at the program level. It’s not criminal, it’s not intentional, but it does cause unnecessary expenses in the program.”

Improper payments are payments that shouldn’t have been made or were made in the wrong amount, according to a 2023 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office. They’re not a measure of fraud.

“About 5% of total Medicaid payments can be found in error,” Hill said. And about 75% of these improper payments involve documentation issues. For instance, doctors didn’t appropriately document why they wrote a certain medical code for a visit. Because Medicaid is a large program, that 5% was about $31 billion in 2024, according to a 2024 report by CMS.

Improper payments don’t mean that the service wasn’t provided, Hill said. “It doesn’t mean that somebody didn’t get care. What it does mean is that the rules that the agencies established for getting payment weren’t followed. All those errors could be corrected,” he said.

Resources

- Dig deeper into understanding fraud and abuse in Medicaid with this KFF online briefing.

- Read KFF’s five key facts about fraud, waste, abuse and improper payments in Medicaid.

- Look at the latest annual report by the Medicaid Fraud Control Units.

- Check out the latest CMS improper payment fact sheet.

- Read GAO’s reports on fraud and improper payments, waste and abuse in federal programs. The office also has a 2024 report on examples of steps taken by CMS to reduce improper payments in Medicare and Medicaid, and actions still needed by CMS and Congress.

- Dig even deeper and see examples in this 2023 HHS report on health care fraud and abuse.

What are Medicaid work requirements?

Medicaid eligibility is mainly based on income. Work requirements, also known as “community engagement” requirements, add new criteria for eligibility: To qualify for Medicaid, low-income adults ages 18 to 64 also have to be working, volunteering or engaging in educational activities for 20 hours a week or 80 hours a month.

Thirteen states proposed and received approval for work requirement programs through Section 1115 waivers between 2017 and 2021, although most were never implemented. Only Arkansas and Georgia implemented the program. The Biden administration rescinded approved proposals in 2021, and some states withdrew them, except for Georgia, which is the only state that still has work requirements in place, according to KFF.

Congressional Republicans may require a federal work requirement for Medicaid as a way to reduce Medicaid spending. A 2023 report by the Congressional Budget Office estimates that the federal government would save $100 billion over a decade with a federal Medicaid work requirement.

But research shows that in the real world, work requirements have large administrative costs and create more barriers for low-income adults to maintain their Medicaid coverage. In addition, most people covered by Medicaid are already working, studies find.

Arkansas implemented the policy in 2018, requiring adults aged 30 to 49 to work 20 hours a week. By 2019, 18,000 had lost their Medicaid coverage.

Studies led by Dr. Benjamin Sommers, a professor of health care economics at Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, find that work requirements didn’t increase employment. Half of the people who lost Medicaid coverage reported serious problems paying off medical debt. Others delayed care and their medications because of the cost. Misinformation and confusion were also major barriers to implementing work requirements.

“It’s a lot of red tape,” said Sommers during a Medicaid webinar hosted by the Chan School on April 17. “They had to report monthly to the state. They had to go through an online portal. Many of the folks didn’t even understand that. They hadn’t heard of the policy, so they didn’t know that they were supposed to be doing anything at all.”

“We found that over 95% already had jobs or should have otherwise met an exemption for the policy, including disability, caretaking, etc.,” said Sommers during the webinar.

Implementation of the work requirement policy cost an estimated $26.1 million, 17% of which was paid for by the state and 83% paid for by the federal government, according to the study, published in the journal Health Affairs in 2020.

Georgia’s experiment with work requirements hasn’t been successful either. Rather than expanding Medicaid, the state opted to experiment with a work requirement program to extend coverage to low-income adults. The program was supposed to cover about 100,000 people.

Instead, about 7,000 people have gained coverage so far, according to the latest state numbers. Implementation of the program cost taxpayers more than $86 million, according to an investigation by ProPublica, published in February.

“I think those are two states that ought to be a real red flag for Congress,” said Sommers during the Chan School’s webinar. “If those two states are telling you their original approach wasn’t successful, we shouldn’t be doubling down and then adopting that as a kind of national standard or we’re going to see more spending on administrative costs and less spending on actual coverage and fewer people enrolled in the program.”

A report released on May 1 by the Commonwealth Fund and the George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health projects that with federal work requirements, up to 5.2 million adults could lose Medicaid coverage in 2026. The policy could also drain state economies by as much as $59 billion and eliminate up to 449,000 jobs. The report also provides state-by-state projections.

Resources

- Read the studies led by Sommers about Arkansas, published in 2019 and 2020.

- Dig deeper with this 2021 paper on public attitudes about Medicaid beneficiaries and work requirements.

- Read KFF’s five key facts about work requirements.

- Read this May 2025 RWJF report, which finds that more than 6 million people could lose Medicaid coverage under a federal work requirement.

- Read ProPublica’s investigation into Georgia’s work requirement program.

- Read the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s state-by-state estimates of Medicaid expansion coverage loss under the federal work requirement.

- Read our May 2023 research roundup on the expanding role of Medicaid in health care.

What are block grants and per capita caps?

As explained above, Medicaid is jointly funded by states and the federal government through a federal match program known as FMAP. This rate varies by state.

Currently, all Medicaid-eligible individuals are entitled to coverage, and states are guaranteed federal matching dollars without a set limit.

Per capita caps and block grants are two other potential ways that Congress could reduce Medicaid spending. Both approaches limit federal dollars given to states, leading to savings, but they could also have negative consequences for people and providers, because the policies shift the Medicaid costs to states.

To make up the difference, states could cut spending in other areas like education, they could cut Medicaid eligibility criteria, cut services, or reduce reimbursement to providers, according to KFF.

With block grants, the federal government would give each state a fixed amount of money each year for Medicaid. The amount won’t increase if the state costs go up, for instance, if enrollment increases due to factors such as an economic downturn.

Under per-capita caps, the federal government caps federal funding per Medicaid enrollee. The caps could be based on all enrollees or separate caps could be calculated based on groups, such as children, adults, older adults and people with disabilities, according to KFF. This approach adjusts for the number of enrollees but doesn’t change if health care costs increase.

“The caps are to cap growth rather than level,” said Layton during the March SciLine briefing. “So, they’ll basically say, like, we’re only going to let the federal contributions go up at a rate slower than the expected Medicaid cost growth. And if that happens, depending on how strict they are, this can decrease [federal] spending significantly.”

But per capita caps could increase states’ Medicaid spending by 7% or $246 billion over a decade if the states were to continue ACA Medicaid expansion coverage, according to an April analysis by KFF, which provides state-by-state estimates.

With reduced federal dollars, states might have to cut Medicaid costs, experts say. They may look to enroll more healthy people and fewer sicker people. States may cut optional Medicaid benefits, such as dental benefits. And they might reduce provider payment rates, which could lead to decreased access to care for beneficiaries, because fewer providers would want to participate in the program.

Resources

- Read KFF’s five key questions about Medicaid block grants and per capita caps.

- KFF also has a recent analysis of the impact of a per capita cap on states.

- The American Hospital Association has a fact sheet on how per capita caps on the Medicaid expansion population could affect the hospitals in each state.

A few research studies to help with your reporting

There are hundreds of research studies about Medicaid, particularly on the impact of Medicaid expansion. Google Scholar is a good place to start looking for the studies. We have curated a list of studies below to inform your reporting.

- Closing Gaps or Holding Steady? The Affordable Care Act, Medicaid Expansion, and Racial Disparities in Coverage, 2010-2021

Benjamin D. Sommers, Rebecca Brooks Smith and Jose F. Figueroa. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, April 2025. - Large Cuts to Medicaid and Other New Policies May Create Untenable Choices for Clinicians in the U.S. (opinion)

Joan Alker. The BMJ, April 2025. - Why Some Nonelderly Adult Medicaid Enrollees Appear Ineligible Based on Their Annual Income

Geena Kim, Alexandra Minicozzi and Chapin White. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, December 2024. - Multigenerational Impacts of Childhood Access to the Safety Net: Early Life Exposure to Medicaid and the Next Generation’s Health

Chloe N. East, Sarah Miller, Marianne Page and Laura R. Wherry. American Economic Review, January 2023. - Exploring the Effects of Medicaid During Childhood on the Economy and the Budget: Working Paper 2023-07

Working paper by the Congressional Budget Office, November 2023. - Preliminary Data on “Unwinding” Continuous Medicaid Coverage

Adrianna McIntyre, Gabriella Aboulafia, and Benjamin D. Sommers. The New England Journal of Medicine, November 2023. - The US Medicaid Program: Coverage, Financing, Reforms, and Implications for Health Equity

Julie M. Donohue; et al. JAMA, September 2022. - The ACA Medicaid Expansion And Perinatal Insurance, Health Care Use, And Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review

Meghan Bellerose, Lauren Collin, and Jamie R. Daw. Health Affairs, January 2022. - Medicaid and Mortality: New Evidence From Linked Survey and Administrative Data

Sarah Miller, Norman Johnson and Laura R. Wherry. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, August 2021. - Lingering Legacies: Public Attitudes about Medicaid Beneficiaries and Work Requirements

Simon F. Haeder, Steven M. Sylvester and Timothy Callaghan. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, April 2021. - Medicaid Expansion and Health: Assessing the Evidence After 5 Years

Heidi Allen and Benjamin D. Sommers. JAMA, September 2019. - Medicaid Work Requirements — Results from the First Year in Arkansas

Benjamin D. Sommers; et al. The New England Journal of Medicine, June 2019 - Association of Medicaid Expansion With 1-Year Mortality Among Patients With End-Stage Renal Disease

Shailender Swaminathan; et al. JAMA, December 2018. - The Effects Of Medicaid Expansion Under The ACA: A Systematic Review

Olena Mazurenko; et al. Health Affairs, June 2018. - Childhood Medicaid Coverage and Later-Life Health Care Utilization

Laura R. Wherry, Sarah Miller, Robert Kaestner and Bruce D. Meyer. The Review of Economics and Statistics, May 2018. - Changes in Mortality After Massachusetts Health Care Reform: A Quasi-experimental Study

Benjamin D. Sommers, Sharon K. Long and Katherine Baicker. Annals of Internal Medicine, May 2014. - Federal Funding Insulated State Budgets From Increased Spending Related To Medicaid Expansion

Benjamin D. Sommers and Jonathan Gruber. Health Affairs, May 2017. - Mortality and Access to Care among Adults after State Medicaid Expansions

Benjamin D. Sommers, Katherine Baicker and Arnold M. Epstein. The New England Journal of Medicine, September 2012. - Also see our two research roundups on Medicaid, here and here.

Expert Commentary