Questions about how social media platforms may drive users into “filter bubbles” — increasingly like-minded communities whose views are reinforced and become more extreme — have been swirling for several years now. As the debate has developed in popular discourse, scholars and data scientists have continued to make insights on what is often referred to in the academic literature as online “homophily,” or colloquially as the “birds of a feather flock together” phenomenon.

In 2013, researchers at Carnegie Mellon University, Stanford and Microsoft Research analyzed anonymized browsing data from more than 1.2 million Web users and concluded that fears over an increasingly personalized Internet could be overblown: Only a “relatively small amount of online news consumption is driven by the more polarized channels, social and search, and opinion pieces — which are typically the focus of laboratory studies — constitute just 6% of consumption relating to world or national news…. [W]e find that individuals typically consume descriptive reporting, and do so by directly visiting a handful of their preferred news outlets.” Further, while social channels and search can lead to “higher segregation” and filter bubbles, those methods of news discovery can also be “associated with higher exposure to opposing perspectives, in contrast to filter-bubble fears.”

Meanwhile, a 2013 paper by a research team at Northeastern University looked at how Google personalized Web search results and found that, on average, “11.7% of search results show differences due to personalization.” According to research by the Pew Internet Project, political discussions on Twitter often show “polarized crowd” characteristics, whereby a liberal and conservative cluster are talking past one another on the same subject, largely relying on different information sources. Other large-scale research on Twitter, such as an analysis of 2012 data by Brown University and University of Toronto researchers, confirms that “groups are disproportionately exposed to like-minded information and that information reaches like-minded users more quickly than users of the opposing ideology.” Political talk on the microblogging platform is typically “highly partisan” and clustered around groups of likeminded users. But evidence that search or microblogging — in and of themselves — are driving further polarization is not easy to obtain.

The questions about polarization in the United States are salient because many of the largest studies and surveys — for example, a giant 2014 Pew Research Center survey report based on responses from more than 10,000 people — confirm that polarization has increased relative to levels seen in recent decades in America. At the same time, social platforms are mediating more of the news and information citizens are consuming. Still, even among top academics studying political polarization in the United States, there are few definitive conclusions, and most scholars point to a variety of explanatory factors that go well beyond Web platforms — and to diverse areas of human behavior.

The latest evidence in the social media polarization debate comes from Facebook data science researchers Eytan Bakshy, Solomon Messing and Lada Adamic (also affiliated with the University of Michigan,) who in May 2015 published a paper in the leading journal Science, “Exposure to Ideologically Diverse News and Opinion on Facebook.” They state that they examined de-identified data relating to 10.1 million users who self-report their ideological affiliation — a small fraction of users overall, and thus a potentially limiting factor — and who consumed news shared through the social network during 2014-2015. Much of what users see is algorithmically curated, and on this point the researchers state the following:

The media that individuals consume on Facebook depends not only on what their friends share, but also on how the News Feed ranking algorithm sorts these articles, and what individuals choose to read. The order in which users see stories in the News Feed depends on many factors, including how often the viewer visits Facebook, how much they interact with certain friends, and how often users have clicked on links to certain websites in News Feed in the past.

The term “cross cutting” refers to content with an ideological bent that is shared by, for example, a liberal, and then is consumed by a conservative, or vice versa.

The study’s findings include:

- Facebook’s algorithm appears to play a limited role in filtering politically tinged news, the researchers conclude: “After [algorithmic] ranking, there is on average slightly less cross-cutting content: conservatives see approximately 5% less cross-cutting content compared to what friends share, while liberals see about 8% less ideologically diverse content.”

- The signals that users give to the algorithm are more powerful than intrinsic choices by the filter: “Individual choice has a larger role in limiting exposure to ideologically cross cutting content: After adjusting for the effect of position (the click rate on a link is negatively correlated with its position in the News Feed), we estimate the factor decrease in the likelihood that an individual clicks on a cross-cutting article relative to the proportion available in News Feed to be 17% for conservatives and 6% for liberals, a pattern consistent with prior research.” Put another way: “Perhaps unsurprisingly, we show that the composition of our social networks is the most important factor limiting the mix of content encountered in social media.”

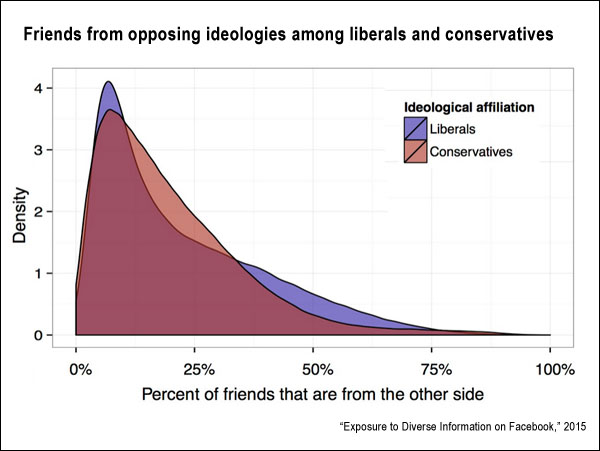

- Sharing is “not symmetric,” with liberals showing less diversity, ideologically speaking, in friendships: “Despite the slightly higher volume of conservatively aligned articles shared, liberals tend to be connected to fewer friends who share information from the other side, compared to their conservative counterparts: 24% of the hard content shared by liberals’ friends are cross-cutting, compared to 35% for conservatives.”

- Content with an ideological bent on hard-news issues is broadly available, but little of it is consumed, relatively speaking: “There is substantial room for individuals to consume more media from the other side: on average, viewers clicked on 7% of hard content available in their feeds.” Further, “While partisans tend to maintain relationships with like-minded contacts … on average more than 20 percent of an individual’s Facebook friends who report an ideological affiliation are from the opposing party, leaving substantial room for exposure to opposing viewpoints.”

The researchers conclude by noting certain limitations within the data: “Facebook’s users tend to be younger, more educated, and female, compared to the U.S. population as a whole. Other forms of social media, such as blogs or Twitter, have been shown to exhibit different patterns of homophily among politically interested users, largely because ties tend to form based primarily upon common topical interests and/or specific content, whereas Facebook ties primarily reflect many different offline social contexts: school, family, social activities, and work, which have been found to be fertile ground for fostering cross-cutting social ties.”

Related: In a commentary for Science on the study in question, David Lazer of Northeastern University/Harvard Kennedy School writes, “Facebook deserves great credit for building a talented research group and for conducting this research in a public way. But there is a broader need for scientists to study these systems in a manner that is independent of the Facebooks of the world. There will be a need at times to speak truth to power, for knowledgeable individuals with appropriate data and analytic skills to act as social critics of this new social order.” Further, Zeynep Tufekci of the University of North Carolina critiques various aspects of the study, while Eszter Hargittai of Northwestern suggests that the large sample used in the study masks some underlying methodological problems.

Keywords: Mark Zuckerberg, Eli Pariser, Fox News, Huffington Post, contagion, social sharing, Facebook, Twitter

Expert Commentary