Media coverage of the Boston Marathon bombings of April 15, 2013, displayed all of the growing pains of a still-evolving digital world that allows both for the virtues of hyper-connected speed and the perils of unconfirmed reports and social media’s raw, unfiltered broadcast capacity. Subsequent reporting has also been marred by false reports and information. The Nieman Journalism Lab has rounded up many of the significant pieces of media criticism published in the wake of the incident. The delicate interplay between speed and accuracy has always been a professional and ethical issue for journalists, but observers saw new dynamics emerging on April 15, with some on Twitter urging restraint and caution, and fighting against the instinct to retweet the latest rumor.

As reporting now shifts to the criminal justice phase of the incident, it is worth reviewing background on several aspects of this story relating to religion and ethnicity. For this, see “Stereotypes of Muslims and Support for the War on Terror”; and “Understanding the Chechen Conflict: Research Roundup and Reading List.”

A new paper from the Harvard Kennedy School, “Preliminary Thoughts and Observations on the Boston Marathon Bombings,” examines a number of lessons learned in terms of preparedness, safety, public and government responses, and leadership.

Some core principles can help guide coverage of disaster, terrorism and public health emergencies, beginning with the Society of Professional Journalists’ “Code of Ethics,” which states at the top that reporters should: “Test the accuracy of information from all sources and exercise care to avoid inadvertent error. Deliberate distortion is never permissible.” Advice more specific to the Boston Marathon attack is provided in detail at the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma. The Poynter Institute is also offering tips that should guide further coverage of the bombing.

Few journalists have as much experience aggressively covering chaotic situations through social media as Andy Carvin of NPR, who has used Twitter to report on unfolding events such as the Arab Spring. Carvin’s demonstrated preference is to directly engage those who post new information and ask for additional evidence and verification, although he notes the emerging professional divide about how to respond properly:

The philosophical split you are seeing here is people that think anything that is a rumor or not confirmed should be hidden in the deepest depths of the newsroom until it is verified, versus what I do, which is acknowledging that certain things are already out there being discussed by the public, and in many cases by the media, and I ask for additional sourcing. And some people don’t like that.

Many news organizations are now struggling to figure out if there should be uniform standards across platforms — if “live blogs” and reporters on Twitter should follow the precise standards guiding what would be said in a television broadcast or written in an article on the front page.

Jeremy Stahl, Slate‘s social media editor, offers further thoughts on Boston-related coverage and “tweeting during a crisis.” Hong Qu at Nieman Journalism Lab provides play-by-play analysis of breaking news and examines lessons learned as events unfolded on April 15.

Terrorism and domestic attacks

Below are background studies, reports and data relating to homeland security threats and attacks that may be useful to news organizations, as the issue of terrorism inevitably resurfaces. The Boston incident happened at a high-profile public event, and there will be questions about security and the state of vigilance among law enforcement. For deep background on these areas, see the Congressional Research Service report titled “Terrorism Information Sharing and the Nationwide Suspicious Activity Report Initiative.”

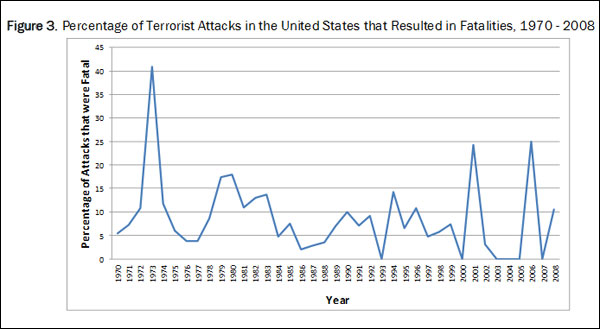

Because the attack’s motivation is not fully known, it is worth considering the spectrum of historical context relating to terrorism, broadly defined. In 2012, the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), at the University of Maryland, issued a report titled “Hot Spots of Terrorism and Other Crimes in the United States, 1970 to 2008.” It quantified the number of such acts on American soil using the following definition for terrorism: “the threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence by a non-state actor to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion, or intimidation.” The following START graphic reflects that definition:

The following material may be of interest to journalists covering these issues:

_______

Analysis

“Hot Spots of Terrorism and Other Crimes in the United States, 1970 to 2008”

Report from the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), University of Maryland, February 2012.

Excerpt: “START and the Global Terrorism Database, on which the Report is based, defines terrorism and terrorist attacks as ‘the threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence by a non-state actor to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion, or intimidation’…. We ask whether certain U.S. counties act as hot spots for terrorist attacks. More than 2,600 terrorist events occurred in the United States between 1970 and 2008. Following past criminological practice, we define hot spots of terrorist attacks as areas experiencing more than the average number of events. While there is evidence of the geographic concentration of terrorist attacks in particular counties (hot spots of terrorist attacks), the data also show that terrorism is widely dispersed, occurring in every state in the country. In total, 65 counties (out of a total of 3,143 U.S. counties) were identified as hot spots of terrorist attacks. While many of these were large, urban city centers (Manhattan, Los Angeles, Miami Dade, San Francisco, Washington DC), terrorist events also cluster in small, more rural counties as well (e.g., Maricopa County, AZ; Middlesex County, MA; Dakota County, NE; Harris County, TX). While the overall percentage of terrorist attacks that result in fatalities is low, the geographic distribution of these events remained similar with large urban centers predominating and yet a good deal of activity in smaller areas as well….

We also ask whether certain counties are prone to a particular type of terrorist attacks (e.g., extreme left-wing, extreme right-wing, ethno-nationalist/separatist, etc.). Ideological motivation could be coded for 1,674 terrorist attacks (64% of all terrorist events from 1970 to 2008) occurring in 475 U.S. counties. Looking at five ideological categories, 88 counties experienced extreme right-wing terrorism (44 counties were identified as hot spots), 120 counties experienced extreme left-wing terrorism (24 counties were identified as hot spots), 26 experienced religiously motivated terrorist acts (3 counties were identified as hot spots), 56 experienced ethno-nationalist/separatist terrorism (6 counties were identified as hot spots), and 185 experienced single issue events (43 counties were identified as hot spots).”

“The State of Global Jihad Online”

Zelin, Aaron. New America Foundation report, January 2013.

Findings: “Comparatively, the jihadi forum ecosystem is not as large as it once was. From 2004 to 2009, there were five to eight popular and functioning global jihadi forums. In the past year, there have been three to five. There are three possible reasons for this decline: (1) global jihadism no longer has the same appeal as in the past; (2) social media platforms are more popular with the younger generation and jihadis have moved their activism to those fronts; and (3) the cyber attacks against the forums over the past six years have degraded online capacity and deterred individuals from joining new forums.”

“Zachary Chesser: A Case Study in Online Islamist Radicalization and Its Meaning for the Threat of Homegrown Terrorism”

Report from the Majority and Minority Staff, Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, February 2012.

Excerpt: “Between September 11, 2001 and February 2012, there were more than 53 cases of homegrown Islamist extremists planning and/or carrying out acts of terrorism against the United States. In the past 12 months alone, there have been 11 homegrown cases including: the arrest of two men who planned to attack a military processing center in Seattle in June 2011; a plot to attack a restaurant frequented by military personnel near Fort Hood, Texas in July 2011and a plan to attack the U.S. Capitol and Pentagon in September 2011.”

“A Comparative Analysis of Suicide Terrorists and Rampage, Workplace, and School Shooters in the United States From 1990 to 2010”

Homicide Studies, October 2012.

Excerpt: “Findings suggest that in the United States from 1990 to 2010, the differences between [suicide terrorists and rampage, workplace, and school shooters] (N = 81) were largely superficial. Prior to their attacks, they struggled with many of the same personal problems, including social marginalization, family problems, work or school problems, and precipitating crisis events.”

“Analyzing the Islamic Extremist Phenomenon in the United States: A Study of Recent Activity”

James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy at Rice University, 2012.

Excerpt: “The study of terrorism strives to identify logic and patterns in a phenomenon that is in constant flux. Weapons, tactics, recruitment, financing, and other elements are fluid as they evolve and adapt to current conditions and the environment. Successful policy requires remaining abreast of the ever-evolving threat and responding accordingly…. Outside of the broad classification assessment that approximately two-thirds of those involved in extremist activities are men under the age of 34, no one, all-encompassing profile can be made of the individuals in the analysis group. Consequently, the data calls for the examination of subgroups and the safeguarding against the development of incorrect stereotypes that might hamper threat detection.”

“Muslim-American Terrorism: Declining Further”

Triangle Center on Terrorism and Homeland Security, University of Chapel Hill, February 2013.

Excerpt: “Fourteen Muslim-Americans were indicted for violent terrorist plots in 2012, down from 21 the year before, bringing the total since 9/11 to 209, or just under 20 per year. The number of plots also dropped from 18 in 2011 to 9 in 2012. For the second year in a row, there were no fatalities or injuries from Muslim-American terrorism. Meanwhile, the United States suffered approximately 14,000 murders in 2012.”

“Estimating the Duration of Jihadi Terror Plots in the United States”

Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, Vol. 35, Issue 12, 2012.

Excerpt: “The estimated mean [terror] plot duration equals 270 days (standard error of mean 40 days), while 95 percent of all plots are estimated to fall between 33 and 750 days. These estimates suggest that on average, approximately three ongoing terror plots have been active in the United States at any point since 11 September 2001.”

“Generating Terrorism Event Databases: Results from the Global Terrorism Database, 1970 to 2008”

Evidence-Based Counterterrorism Policy, Vol. 3, 2012.

Excerpt: “While social and behavioral research on terrorism has expanded dramatically in recent years, theoretical perspectives that incorporate terrorism and the collection of valid data on terrorism have lagged behind other criminological specializations. Despite the enormous resources devoted to countering terrorism, we have surprisingly little empirical information about which strategies are most effective.”

“Homegrown Terrorism; the Known Unknown”

University of Essex, United Kingdom, September 2012.

Excerpt: “Homegrown terrorism is a separate strain of domestic terrorism due to ideological character of political Islam, yet differing from international terrorism in targeting patterns. The implications of the study are that counterterrorism efforts for homegrown terrorism should resemble those of domestic terrorism rather than international terrorism.”

Forecasting, preparedness

“Forecasting Terrorism: The Need for a More Systematic Approach”

Journal of Strategic Security, Vol. 5, 2012.

Excerpt: “In general, the track record of forecasting terrorism has not been good. This is particularly true for major changes in the modus operandi of terrorism, the attacks on 9/11 being a case in point. The analyses of the future of terrorism shows an absence of methodologies, and the lack of theoretical foundations, which lead to limited insights about the causes of changes in terrorism. Most forecasts seem to say more about the present state of terrorism than about the future.”

“Identifying Terrorists using Banking Data”

B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, December 2012.

Excerpt: “The fight against terrorism requires identifying potential terrorists before they have the opportunity to act. In this paper, we investigate the extent to which retail banking data — which as far as we know are not currently used by anti-terror intelligence agencies in any systematic manner — are a useful tool in identifying terrorists.”

“The Organizational Correlates of Terrorism Response Preparedness in Local Police Departments”

Criminal Justice Policy Review, Vol. 23, No. 3, September 2012.

Excerpt: “Community policing efforts are positively correlated with terrorism preparedness efforts. Results also show that a number of organizational factors including organization size, budget per capita, and functional differentiation were positively correlated with terrorism preparedness, whereas formalization and spatial differentiation were negatively correlated.”

Media

“Does Watching the News Affect Fear of Terrorism? The Importance of Media Exposure on Terrorism Fear”

Crime & Deliquency, Vol. 58, No. 5, September 2012.

Excerpt: “Research suggests that fear of crime is related to the overall amount of media consumption, resonance of news reports, how much attention the individual pays to the news, and how credible he or she believes it to be. The present study examines whether the same applies for terrorism. We use telephone survey data (N = 532) of New Yorkers and Washingtonians to test whether perceived risk and fear of terrorism are associated with several media-related variables. We find that exposure to terrorism-related news is positively associated with perceived risk of terrorism to self and others and with fear for others, but not for self.”

Tags: research roundup, terrorism, crime, Twitter, policing

Expert Commentary