From the moment the baby-boom generation took its first steps in 1946, its members have had an enormous impact on the United States. They powered the suburbanization of America in the 1950s, youth rebellion in the 1960s and the “Me Decade” of the 1970s. And now as they approach retirement, their sheer numbers will continue to drive societal change.

A May 2014 report from the Census Bureau shows that by 2050 the number of U.S. residents over 65 will nearly double compared to 2012 levels — 83.7 million versus 43.1 million. Because of improvements in health care, declines in smoking rates and other factors, retirees’ life expectancy is increasing as well: In 1972, someone aged 65 would on average live another 15 years; by 2010, the figure rose to 19 years.

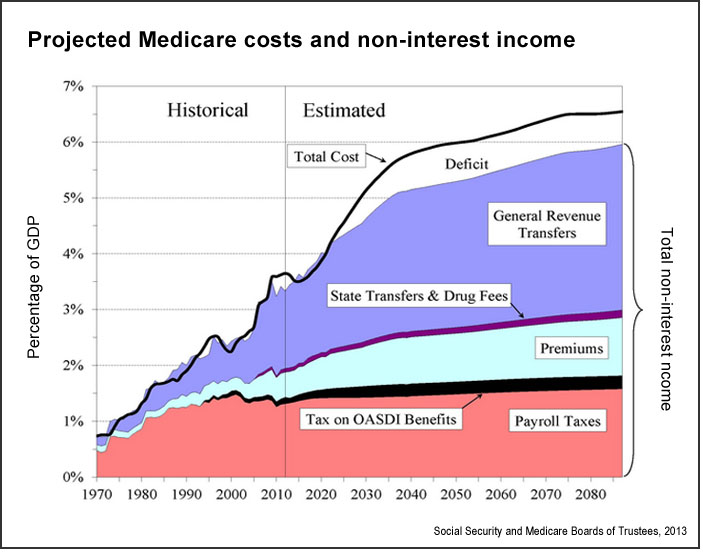

Those extra years don’t come without costs: Retirees continue to draw Social Security and receive medical benefits, even as the proportion of U.S. residents working falls. The Social Security and Medicare Trustees have reported that Social Security costs will exceed income starting in 2021, and assets will be potentially exhausted in 2033. The Disability Insurance trust fund is in significantly worse shape: It will run out of assets by 2016. The date of asset exhaustion for the Medicare Hospitalization Insurance trust fund is 2024. State and local governments feel the pinch as well, as pensions promised during economic flush times often prove difficult to honor as costs rise and payrolls shrink.

A 2014 study published in the Annual Review of Political Science, “State and Local Government Finance: The New Fiscal Ice Age,” looks at the broader impacts of the aging of the country’s population. The researchers — D. Roderick Kiewiet of the California Institute of Technology and Mathew D. McCubbins of Duke University — review academic literature and look at the impact of the Great Recession and demographic shifts on state and local finance. They note that as Medicaid and retirement costs increase, governments will have “less to spend on transportation, parks and recreation, education, public safety, and all the other services.”

The study’s findings include:

- Medicaid is a joint federal/state program and isn’t financed by a tax-supported trust fund. Thus as costs rise, the bite comes out of general funds: “Total state spending on Medicaid started at low levels — $2.3 billion in 1970 — but grew rapidly. State Medicaid expenditures reached $11.2 billion in 1980, $31.3 billion in 1990, $89.2 billion in 2000, and $131.7 billion in 2010. Medicaid now accounts for about 17% of state general budget expenditures and is the second largest category of spending after elementary and secondary education.”

- For the past 20 years, state and local government employees have been retiring at a faster pace than the general population, 3.75% annually versus less than 1%. In 2013 there were approximately 9 million people receiving state and local government retirement benefits, and the number will increase to 18 million by 2030. Contributions to many pension plans have been inadequate, however, and returns on investments were hit hard by the recession. By the 2013 fiscal year, the unfunded pension liabilities of state and local governments were estimated to be $2.8 trillion.

- Some state and local governments have addressed pension shortfalls through the issuance of long-term bonds, called pension-obligation bonds (POBs) — about $64 billion of such bonds were outstanding in 2013. The practice is not just risky, but also has a range of drawbacks: Interest rates paid are higher; the obligations (pensions) don’t pay large, long-term economic benefits, unlike the infrastructure that bonds generally fund; and if the investment results disappoint, governments find themselves in even worse situations.

- The Great Recession had an even larger negative effect on state and local tax receipts than it did on real GDP. “As in previous recessions, sales tax revenues were the first to decline, but income tax revenues soon followed and fell more sharply. In the second quarter of 2009, personal income tax revenue had fallen by 27% from the previous year, contributing to an overall 17% decline in total state tax collections.”

- Property tax receipts remained low even after sales and income tax receipts began to recover in 2010: “Three years after the economy had bottomed out, property tax revenues were 1% lower than at the trough of the recession. This far into the recovery from previous recessions, property tax receipts were on average 10% higher.”

- While the last resort of municipal bankruptcy is an “unappealing choice,” it can serve a useful purpose, allowing governments to maintain essential services while reorganizing their finances. However, many troubled cities are doing everything possible to avoid bankruptcy: “Streets go unpaved; parks and schools are closed. Street lights are extinguished or removed entirely…. As the record of those cities that have recently declared bankruptcy attests, draconian cuts to basic municipal services produce precisely the death spiral that Chapter 9 bankruptcy was designed to prevent.”

- Prudent fiscal adaptation to the coming demographic shift is mandatory, be it through decreasing costs, increasing revenues, or well-structured public-private partnerships. However, voters “have repeatedly chosen to put into power those who favor denial, delay, and expediency over adaptation. Every day that fiscal adjustments are delayed makes the adjustments all the more wrenching when they do occur, which they inevitably must.”

The researchers emphasize that the ongoing changes are not the result of a crisis — a brief episode that eventually passes — but the beginnings of an enduring change: “The United States is in the throes of a long-term shift from the favorable demographic and economic conditions of the past to the far less favorable conditions of the future…. The fiscal [situation] confronting state and local governments will not improve during the lifetime of anyone reading this article. Indeed, in most places, fiscal conditions will become increasingly harsh.”

Related research: A December 2013 Federal Reserve working paper, “Walking a Tightrope: Are U.S. State and Local Governments on a Fiscally Sustainable Path?” The authors, Bo Zhao of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston and David Coyne of U.C. San Diego, measure the “trend gap” between actuarially required contributions (ARCs) to pension and other post-employment benefits (OPEB). “The nationwide per-capita trend gap without pension or OPEB ARCs was already above zero during most of the 2000s. The full trend gap … reached over $1,000 per capita in 2010.” Without pension liabilities, the gap ranged between $700 and $1,000 per capita.

Keywords: fiscal crisis, budget crisis, demographics, balanced budget, budget cuts, public-private partnership, aging, elderly issues

Expert Commentary