During much of the second half of the 20th century, Americans got their news and civic information primarily through a few dominant sources, usually a newspaper that had a relative monopoly on local information and one of three major television networks. With the rise of the Web, there was a sense that things were changing, and many hoped that citizens would be better informed by a broader, richer and more representative and democratic array of media streams. The number of “filters” would vastly expand.

The advent of social media and peer-to-peer technologies offers the possibility of driving the full democratization of news and information, undercutting the agenda-setting of large media outlets and their relative control of news and information flows. We are now about 10 years into the era of the “social Web.” Yet, despite a pervasive sense that “everything is different,” the current data do not suggest a radical shift or a totally linear march toward a diffused, distributed and “flattened” environment. Rather, a hybrid media ecosystem has emerged. What, precisely, are its contours?

A 2014 paper for the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School, “The Challenges of Democratizing News and Information: Examining Data on Social Media, Viral Patterns and Digital Influence,” consolidates media industry data and perspective — from NPR, the Boston Globe and the Wall Street Journal — and synthesizes a growing body of social science and computational research produced by universities and firms such as Microsoft Research and the Facebook data science team, as well as survey findings from the Pew Research Center.

The paper first analyzes patterns of news content sharing on social media, then explores research about the behavior of social networks at the technical level and implications for media. The study, by John Wihbey of the Shorenstein Center, is based on interviews with leading social media practitioners and media scholars, as well as internal social media data from NPR and the Boston Globe. Interviewees include Clay Shirky of New York University, Duncan Watts of Microsoft Research, James Fowler of UCSD, Talia Stroud of UT Austin, Sarah Marshall of the Wall Street Journal, Patrick Cooper of NPR and Joel Abrams of the Boston Globe.

The paper’s findings include:

Audience habits

- The ingrained habits of average people seeking and engaging with news and information have not changed as dramatically as some might have expected. Surveys from Gallup, the Pew Research Center, the Reuters Institute and the American Press Institute suggest that while social media are playing a bigger role in news consumption and people are finding more news this way, direct streams from mainstream media organizations still dominate the news and information space across the U.S. population.

- Computational analysis of the browsing habits of news consumers indicates that direct access to large news sites continues to characterize even the majority of online news consumption (and most people circle back to one or two sites.) A small fraction of news is accessed through social media and personalized networks. It is an analytical mistake to extrapolate from the habits of “information elites” and heavy users of Twitter, Reddit and the like, who still represent only a small fraction of news consumers.

- It is true that production of news and information has been substantially democratized, but the delivery, or “last mile,” necessary to reach broad audiences has not. A “power law” still characterizes the distribution of public attention to news and information.

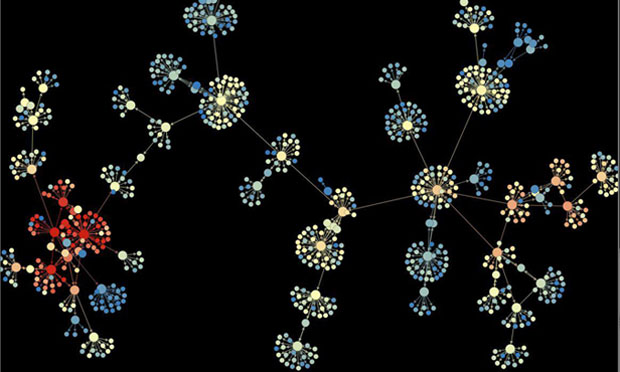

- Most news does not spread “virally,” through infectious, “epidemic” patterns. A 2014 study from Stanford University and Microsoft Research found that most content shared online reaches just a few people, and most sharing cascades on networks are short and shallow. Truly viral events, featuring large swells of “bottom up” peer-to-peer sharing by crowds, are exceedingly rare — they occur at a rate of perhaps one in a million across content shared online, including news. When content achieves significant audience reach, it is almost always explained by a large, one-to-many broadcast from an established outlet.

Case studies in social media data

- Some news organizations are seeing significant sharing and peer-to-peer behavior around their content, though the degree to which this is true varies widely. For example: According to internal analytics data from NPR, among the 55 million visits (first-time and returning visitors together) to NPR.org in February 2014, 43.2% — 23.8 million — came through social media. Of those, about 12.7 million — roughly 23% of traffic overall — during that time were the result of peer-to-peer social sharing through Facebook, Twitter, Reddit or StumbleUpon. About 45% of NPR’s Facebook traffic was the result of genuine peer-to-peer effects during that period (as opposed to receiving it directly through the NPR Facebook page feed). This suggests that, even for a highly successful digital news organization, only 1 in 5 visitors comes as a result of a truly viral, or peer-to-peer, phenomenon.

- According to internal data from the Boston Globe, 18.9% of traffic for BostonGlobe.com in March 2014 came from social media, while 32.9% came directly to the site and 27.2% from search. In March 2014, the 50 stories with the most social media referrals saw 50% or more of their views come from social channels, and the content varied widely — a story about the death of firefighters; a Sunday feature about learning in old age; a New England Patriots controversy. A snapshot of that metro daily’s social media referral patterns reveals real diversity in terms of its social audience’s consumption preferences.

Social network dynamics

- There is an emerging skepticism about the degree to which social media can lead to deep or consistent engagement with news content. Scholars and media practitioners are only in the early stages of understanding why people share content and how to facilitate “thicker” engagement.

- Although the conventional wisdom is that social networking technologies extend the power and reach of information almost infinitely — and create an entirely new ecosystem — careful social science research and empirical evidence reveals a tighter relationship between offline and online worlds than many believe. The world of digital networks is more constrained by traditional human habits than meets the eye. The size of people’s core social networks has remained roughly the same over time; having a real-world relationship with someone, in addition to an online one, remains a key predictor of how and whether information will be shared, consumed, absorbed and acted upon.

- Social networks such as Facebook enable the development of more casual acquaintances, or “weak ties,” but it is unclear what this means in terms of wider exposure to news and information, as our “strong ties” are much more likely to influence our information habits, even online. Evidence is still being gathered, of course, and scholars and analysts are still debating whether fundamental changes in human social behavior are at hand (and thus new dynamics around the facilitation of information broadcasts and diffusion).

- Two pioneering 2014 studies from Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society and MIT’s Center for Civic Media using the Media Cloud platform attempted to map the entire life-cycle of stories passing through the online ecosystem — one on the SOPA/PIPA legislative controversy and one on the Trayvon Martin story. The studies arrived at slightly differing conclusions. In the case of SOPA/PIPA, a more distributed media system, with many empowered smaller voices, helped build attention for the story, while in the Martin case, smaller voices also mattered, but traditional broadcast media played a decisive role at moments when the story might otherwise have lost mass attention. (Also see a similar Media Cloud-driven analysis of the “net neutrality” campaign.)

“Whether the information ecosystem will tip toward more gatekeepers or grassroots in terms of agenda-setting is a largely abstract question — perhaps the networked media world is now too big and diverse to expect a single answer, and it will vary from issue to issue, story to story,” the paper concludes. “What is increasingly clear, however, is that a hybrid system has begun to evolve, one that can be at times just as unequal in terms of voice, power and attention, despite all of technology’s promise.”

Related research: The Shorenstein Center paper is also based in part on a multiyear effort to track and synthesize the latest research on social and digital media, the findings of which are regularly published in a column for Nieman Journalism Lab.

Keywords: Facebook, Twitter, news

Expert Commentary