From the latest economic and consumer surveys to polls about the current political leadership and overall trust in institutions, there are many ways of capturing the “mood” of Americans and measuring sentiment about where the country is headed over the long term. In recent years, many of these surveys have shown a general decline in the sunny optimism often associated with America’s cultural outlook. Part of this has been driven by growing income inequality across American society; the U.S. Census Bureau reported in August 2014 that the gap between higher- and lower-wealth households continues to widen.

One particularly revealing line of inquiry relates to the degree of confidence that parents have in the proposition that their children will have a better life than they do. It’s a deeply subjective question, of course, often worded slightly differently across polls; and it’s also true that during periods of economic distress, Americans reliably turn pessimistic. To discern any long-term shifts, it is worthwhile reviewing the aggregated data.

The latest major survey to ask a version of this question, an August 2014 Wall Street Journal/NBC poll, found that “76% of adults lack confidence that their children’s generation will have a better life than they do — an all-time high.” Asked whether or not “life for our children’s generation will be better than it has been for us,” just 21% of respondents said “yes.” This prompted some commentators to speculate about a collective “lost faith in the United States,” and polling experts to contemplate what it means for the country to settle into “an uncertainty about the future.” Yet it is worth noting that pessimism on this generational “quality of life” question has been expressed by a majority of Americans for more than two decades. (See historical responses on this Wall Street Journal/NBC poll question, going back to 1992.)

A 2013 Heartland Monitor Poll, run by National Journal and AllState, reported similar findings in a report titled “The American Dream: Under Threat.” Meanwhile, polling data from Gallup, among other sources, has revealed an interesting split between the sentiments of parents and their offspring. In a January 2013 survey of 5th- through 12th-graders, nearly all were optimistic: They were either “very likely (43%) or somewhat likely (52%) to have a better standard of living, better homes and a better education than their parents.” By contrast, Gallup found in a parallel poll of adults at that time that “Americans are evenly divided about whether it is likely (49%) or unlikely (50%) that the next generation of youth in the country will have a better life than their parents.” For historical context, Gallup notes that “views today remain depressed compared with 2008 through early 2010, when Gallup polls found solid majorities of Americans feeling optimistic that young people’s standard of living would eclipse their parents’. Prior to that, in polls conducted by other survey firms between 1998 and 2003, optimism on this question was also dominant. One has to go back to 1995 to find the public about evenly split, as it is today.”

A 2012 Pew Research Center report, “The Lost Decade of the Middle Class,” notes that about “43% of those in the middle class expect that their children’s standard of living will be better than their own, while 26% think it will be worse and 21% think it will be about the same.” Further, 85% of respondents said it is “more difficult” for “middle-class people to maintain their standard of living” compared with a decade ago. When asked if it was likewise “harder to get ahead today” than 10 years ago, 71% of middle-class respondents agreed.

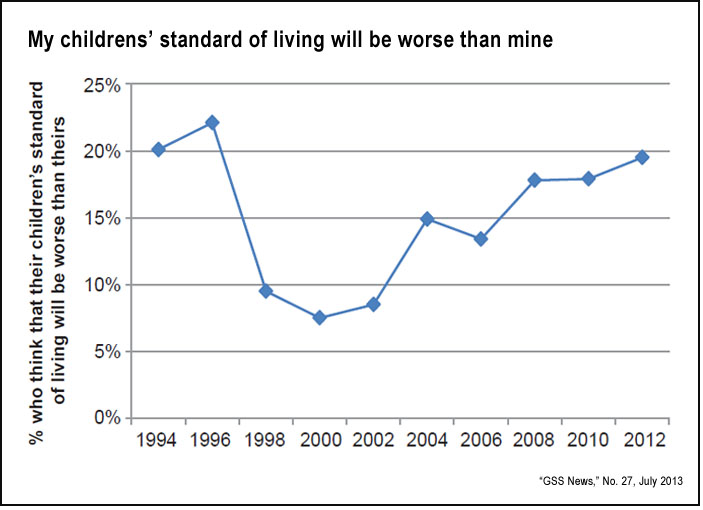

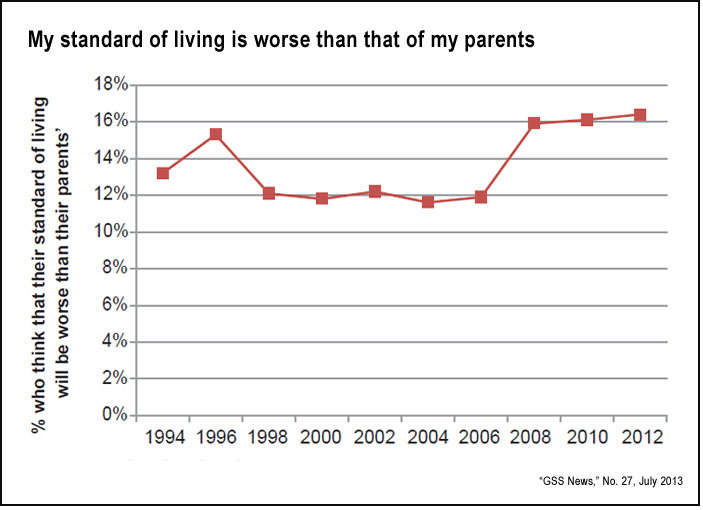

To discern truly valid trends, it is useful to look at long patterns of U.S. public sentiment. Another trusted source is the General Social Survey (GSS), run by the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) at the University of Chicago. The GSS has been conducted for more than four decades, since 1972. Scholars there issued a research brief in July 2013 with some insights into how the Great Recession may be affecting public attitudes. (Also see the wider 2013 report on economic well-being.) The report notes that the “percentages of those who identified as lower class, of those who said that they were worse-off financially than their parents, and of those who predicted that their children would be worse-off than they themselves either worsened or showed no improvement from 2010 to 2012.”

Below are two key GSS charts with long-term perspective on these generational perception issues:

Related research: A 2011 report by the Pew Charitable Trusts, “Downward Mobility from the Middle Class: Waking Up from the American Dream,” studies the factors that contribute to downward mobility and how these factors intersect with race and gender. Based on data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, the report compared the economic status of youths who lived in their parents’ homes in 1979 to their economic status in 2004 and 2006, at 39 to 44 years of age. Also of interest is “The Economic Impacts of Tax Expenditures: Evidence from Spatial Variation across the U.S.,” which looks at intergenerational income mobility — the chance of a child from the bottom fifth of income rising to the top fifth by the time he or she is an adult.

Keywords: public opinion, intergenerational mobility, poverty, children, surveys, polls

Expert Commentary