News of another mass shooting at Ford Hood, Texas, follows other recent high-profile mass killings, such as the murder of 12 people at the Washington Navy Yard on Sept. 16, 2013. As the investigation continues to unfold — and more is learned about the perpetrator and the experience of victims — it is worth considering some relevant data and academic findings that may help contextualize these events.

In March 2013, the Congressional Research Service issued a report, “Public Mass Shootings in the United States,” that defines such events as follows: “These are incidents occurring in relatively public places, involving four or more deaths — not including the shooter(s) — and gunmen who select victims somewhat indiscriminately. The violence in these cases is not a means to an end — the gunmen do not pursue criminal profit or kill in the name of terrorist ideologies, for example.” The researchers conclude:

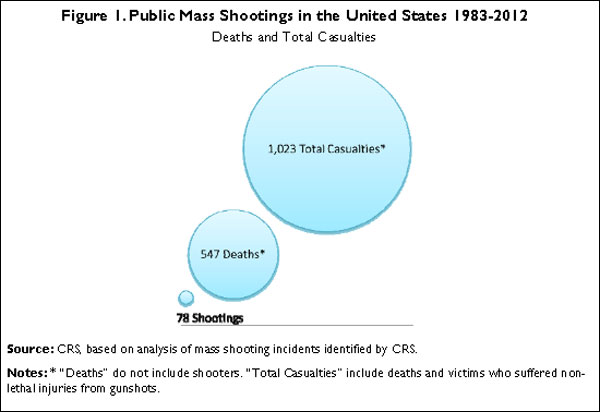

Applying this understanding of the issue, the Congressional Research Service (CRS) has identified 78 public mass shootings that have occurred in the United States since 1983. This suggests the scale of this threat and is intended as a thorough review of the phenomenon but should not be characterized as exhaustive or definitive. According to CRS estimates, over the last three decades public mass shootings have claimed 547 lives and led to an additional 476 injured victims. Significantly, while tragic and shocking, public mass shootings account for few of the murders or non-negligent homicides related to firearms that occur annually in the United States.

Among the 78 mass shootings between 1983 and 2012, 26 happened at the workplace of the shooter. Although experts agree that detailing potential shooter profiles remains problematic, the report’s authors note that “there are some observations that can be made regarding public mass shooters. For instance, among the public mass shooting incidents reviewed by CRS, the gunmen generally acted alone, were usually white and male, and often died during the shooting incident. The average age of the shooters in the incidents identified by CRS was 33.5 years.”

Statistics relating to mass shootings can be parsed in many ways, leading to different counts and conclusions. Brad Plumer at the Washington Post‘s “WonkBlog” summarizes findings from a coalition of mayors — an advocacy group committed to gun control — who issued their own report. That 2013 report also finds that, overall, mass shootings account for relatively few murders as compared with those resulting from more “routine” gun violence. Using a more expansive definition of “mass shooting,” the report found that there had been “56 mass shootings — more than one per month — that occurred in 30 states” between January 2009 and January 2013. The group finds that “less than one percent of gun murder victims recorded by the FBI in 2010 were killed in incidents with four or more victims.”

The Post also furnishes a graphic featuring the 12 deadliest shooting incidents in U.S. history. It is worth noting that half — incidents at Virginia Tech, Aurora, Sandy Hook, Binghamton, Fort Hood and now the Washington Navy Yard — have taken place since 2007.

A Texas State University report issued in 2013 found that, between 2001 and 2010, “active shooter events” occurred 84 times; the median number of deaths is two, while the median figure for those shot is four. The researchers define such incidents as an event involving “one or more persons engaged in killing or attempting to kill multiple people in an area (or areas) occupied by multiple unrelated individuals.” They conclude: “The frequency of ASEs appears to be increasing…. Business locations were the most frequently attacked (37%), followed by schools (34%), and public (outdoor) venues (17%).”

For a sense of the research around establishing potential profiles of perpetrators of mass shootings, see this review of the scholarship on “rampage violence.” Still, academic theory around these particular kinds of events is not well settled. In a 2012 American Journal of Public Health article, “Rampage Violence Requires a New Type of Research,” John M. Harris Jr and Robin B. Harris of the University of Arizona cast doubt on the adequacy of existing scholarship:

Rampage violence seems to lead to repeated cycles of anguish, investigation, recrimination and heated debate, with little real progress in prevention. It is time to acknowledge the futility of this approach. Either rampage violence is unpredictable and unsolvable or our current approaches to predicting and preventing it are not working. If we accept the possibility of progress, then we should also accept that our current violence research methods may need adjustment.

Of course, although such violence continues to be shocking, many trends relating to overall levels of gun violence continue to suggest positive shifts in American society. A May 2013 Pew Research Center report titled “Gun Homicide Rate Down 49% Since 1993 Peak; Public Unaware” has more on the disjunction between public perception and reality.

Expert Commentary