The 1994 Rwandan genocide represents one of the most tragic episodes of political violence in recent history. Estimates suggest that in just 100 days, conflict between the Hutu majority and Tutsi minority resulted in the killing of between 500,000 and 1 million citizens. In response to the genocide, the United Nations created a criminal tribunal for Rwanda, and 77,000 people have been prosecuted for being members or accomplices of armed militias that carried out attacks and 433,000 for engaging in localized violence.

The role of the media during the genocide received considerable attention from scholars and human-rights activists: Some Rwandan media organizations urged individuals to take part in the killings and increased levels of violence, while international media organizations often gave scant coverage of the events. Addressing the Symposium on the Media and the Rwanda Genocide in 2004, former Secretary General of the United Nations Kofi Annan said: “Western news media for the most part turned away, then muddled the story when they did pay attention. And hate media organs in Rwanda — through their journalists, broadcasters and media executives — played an instrumental role in laying the groundwork for genocide, then actively participated in the extermination campaign.”

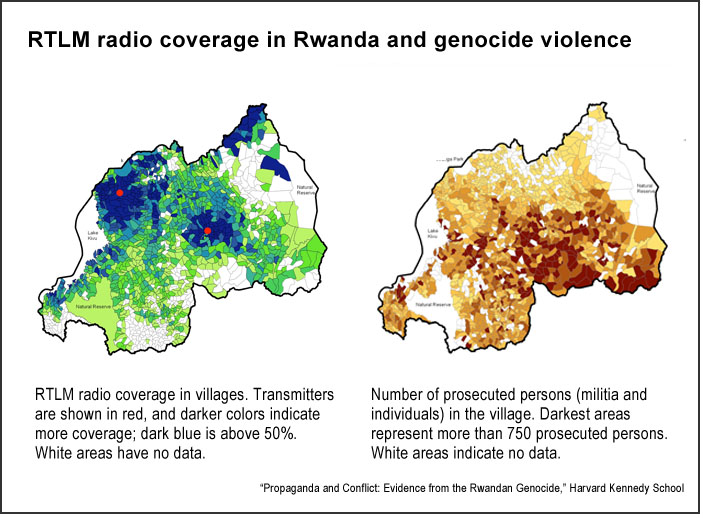

A 2014 paper published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, “Propaganda and Conflict: Evidence from the Rwandan Genocide,” looks at the impact of Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM), a key media outlet for the Hutu-led government, on violence and killings of the Tutsi minority. The study, by David Yanagizawa-Drott from the Harvard Kennedy School, analyzes how exposure to propaganda and inflammatory messages calling for the extermination of the Tutsis fueled violence by the Hutu population.

Using a village-level dataset, the author tests two hypotheses: The first examines the direct effect of exposure to RTLM broadcasts on violence levels in those villages, mainly through persuasion. The second analyzes the social interactions and spillover effects from RTLM listeners to non-listeners in nearby villages, through social interactions. Both militia-led violence and localized, individual violence were analyzed.

The paper represents a departure from previous qualitative studies, as it uses geographical tools (ArcGIS) to establish the difference in the levels of violence between a group of individuals that was within the reach of RTLM broadcasts and a control group that, because of the geographical features of Rwanda, was outside the station’s transmission area.

The study’s main findings are:

- Approximately 51,000 perpetrators (10% of overall participation in the Rwandan genocide) can be attributed to the station’s broadcasts, and almost one-third of the violence by militias and other armed groups.

- Full exposure to RTLM broadcasts increased the number of persons prosecuted for any type of violence (militia violence or individual violence) up to 69%. On average, a one standard deviation increase in radio coverage increased total violence participation as much as 13%. The estimated effects of RTLM reception were statistically significant at the 5% level.

- For low-level increases in radio coverage, there seems to have been no rise in the population’s participation in violence. However, when a critical threshold of coverage is reached, there is a significant rise in violence.

- Education levels and the relative proportions of the majority and minority populations played significant roles in the impact of RTLM broadcasts: “Propaganda encouraging violence against an ethnic minority appears to be more capable of inducing participation when the minority is relatively small and defenseless, and when the targeted audience lacks basic education.”

- Broadcasts effectively mixed exhortations to violence, threats and promises; and because they were endorsed by the government and armed forces, they had the weight of signaling official policy: “Taken together, these factors make it abundantly clear that Hutus listening to RTLM broadcasts had good reason to fundamentally revise their beliefs about the cost-benefit tradeoff of participation and non-participation.”

- For militia violence, spillover effects within 10 kilometers are statistically significant and substantially important: “A one standard deviation increase in the share of the population in nearby villages with radio reception increases participation in militia violence by 47.6%.”

- Direct effects and spillover effects may interact: “RTLM persuaded some militia members who listened to the radio to join the genocide [direct effect], and a consequence this led to higher mobilization among militia members in neighboring villages via peer influences [spillover effect].”

In conclusion, the author writes: “Allowing the station to broadcast had substantial human costs, with consequences detrimental for the targeted population. In addition, the violence may have had long-term impact on human capital formation, social capital, and political stability.”

Further readings: See more comments from Yanagizawa-Drott on his study and its implications for how we think about media and political violence:

A list of transcripts from all broadcasts by RTLM between July 1993 and July 1994 are available on the Rwanda File website. A 2013 paper published in the Annual Review of Law and Social Science, “The Justice Cascade: The Origins and Effectiveness of Prosecutions of Human Rights Violations,” present a cross-national view of trends in human rights prosecutions. The authors trace the origins of individual criminal accountability, the process by which this new norm has spread globally, and its impact on repression levels in those countries and regions where prosecutions have taken place.

Keywords: conflict, genocide, mass media, social interactions, propaganda, violence

Expert Commentary