In a 2014 report, the U.S. State Department reveals dire human-rights abuses in nations around the globe, from Egypt to Russia, Syria to Cuba, China to South Sudan. Research has demonstrated the importance of membership of international organizations to prevent future violations and promoting human rights norms, and the role of a free press. However, debate continues about whether the most direct way of holding human rights abusers accountable — putting them on trial — has a deterrent effect, or if it can prolong conflicts and even lead to more abuses.

The concept of holding individuals criminally accountable for human rights violations first emerged with the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials after World War II. Prosecution efforts continued on a domestic level in Greece and Portugal in the 1970s and Latin America in the 1980s, and in the 1990s international criminal tribunals were established for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda. The creation of a permanent International Criminal Court in 2002 put the spotlight on prosecuting human rights abusers, but several controversial cases have led to questions about the effectiveness of the ICC.

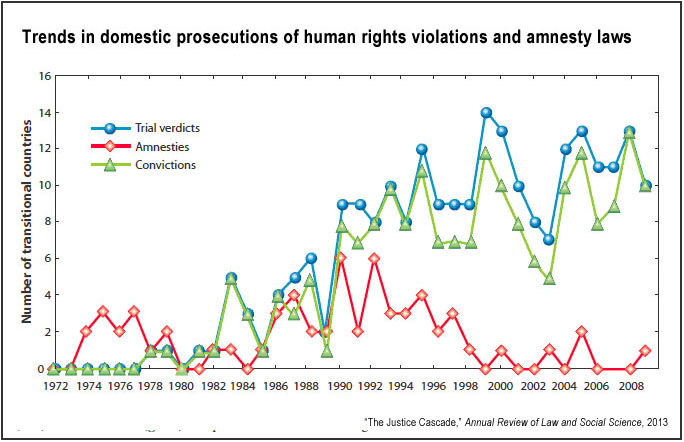

The fragmented nature of human rights prosecutions has made it difficult to understand the scale of the move toward holding individuals accountable. A 2013 paper published in the Annual Review of Law and Social Science, “The Justice Cascade: The Origins and Effectiveness of Prosecutions of Human Rights Violations,” uses new data to present a cross-national view of trends in human rights prosecutions. The authors — Kathryn Sikkink, now of the Harvard Kennedy School, and Hun Joon Kim of Griffith University, Australia — trace the origins of individual criminal accountability, the process by which this new norm has spread globally, and its impact on repression levels in those countries and regions where prosecutions have taken place.

The study’s findings include:

- Prosecutions for human rights violations have a strong and statistically significant downward impact on levels of repression, even when controlling for other factors such as democracy, civil war, economic conditions and past levels of repression.

- The number of prosecutions in a given year and the length of time a country has been prosecuting human rights violations further reduce a country’s repression score. If a country were to move from the minimum (0) to the maximum possible number of prosecution years (20) this would bring approximately a 3.8% decrease in the repression scale.

- From the 1990s on, there was an increase in human rights prosecutions and verdicts. At the same time, while fewer countries were adopting new amnesty laws, a large number of countries still have such laws in place. Thus, increasing prosecutions are not replacing amnesty laws but taking place alongside them.

- Latin America and Central and Eastern Europe have seen the greatest trend toward domestic human rights prosecutions. However, Latin America has had no international prosecutions; instead, Europe and Africa are heavily represented because of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda.

- Countries that do not prosecute human rights violations appear to benefit from a regional deterrence effect, as measured by future levels of repression, if four or more of their neighbors do prosecute violations.

- The entire prosecution process is associated with improvements in human rights situations, but prosecutions that result in convictions appear to have a greater effect than those that do not. However, in cases of torture, even prosecutions that do not result in conviction appear to have a deterrence effect.

- While previous research has shown that civil war leads to increased human rights violations, the authors found no evidence that prosecuting such violations worsened repression in those countries.

The authors conclude that while prosecutions “are not a panacea for human rights problems; they appear to be one form of sanction that can contribute to the institutional and political changes necessary to limit repression.” The paper closes with a brief discussion of research that has shown prosecutions may be more effective when combined with amnesties. One explanation offered is that amnesties stop perpetrators from forming a united front by splitting them between those who would benefit from an amnesty and those who would not.

Keywords: human rights violations, prosecutions, truth and reconciliation commissions, deterrence effect

Expert Commentary