It began with a story about the handling of a 911 call in Wichita, Kansas.

In June 2019, the medical director of emergency medical services in Sedgwick County had gone to the apartment of a man with a self-inflicted gunshot wound and decided that he should be left to die, even though the man had a pulse and labored breathing. At The Wichita Eagle, Chance Swaim and Michael Stavola reported the story in March 2021, shortly after the state investigation records were released, two years after the incident.

“After we reported that [first story] it was immediately like the floodgates opened on the EMS employees who had been waiting to speak up and speak out for two years,” says Swaim, the lead reporter of the series. “I don’t know if they thought we weren’t interested in the story or what, but once that story broke, many of them talked to us and told us what was going on in their department.”

By July, Swaim, an investigative reporter, and Stavola, a breaking news reporter, had a three-part series exposing a broken EMS system with staffing shortages and dangerously slow response times. The series was followed by more stories and developments that are still unfolding. About a week after the series ran, the Sedgwick County EMS Medical Director, Dr. John Gallagher, resigned.

I reached out to the reporters to learn more about how they did the investigation, how the series affected them and how they used academic research to vet the false claims of a powerful public figure.

“People under political pressure or other things may have an incentive to downplay the seriousness of a situation — or give misinformation or allow misinformation to stay out there if it benefits them,” Swaim says. “But there’s a lot of impartial research out there that gives you the facts outside of the political realm.”

Swaim spoke with me via phone and answered the bulk of my questions. Stavola answered additional questions via email. The interviews have been edited for clarity and length.

Naseem Miller: Chance, how did you get into journalism?

Chance Swaim: I was born and raised here in Wichita, Kansas. The Wichita Eagle is my hometown paper. I finished my undergraduate degree in English literature at Wichita State University and had been working construction full time through school. And once I got my degree, I was like, I think I can do something and with my brain now and walked into The Wichita Eagle office and said, “Hey, I want to be a reporter.”

They introduced me to one of their interns who was the editor of The Sunflower, [the independent, student-run publication at Wichita State]. I was also starting graduate school in creative writing.

As soon as I finished my MFA in Creative Writing, I got hired on at The Eagle as a breaking news and cops reporter in 2018, and within a year I was able to move up to investigative reporter.

NM: I’m curious, was there anything you learned in construction that could apply to journalism?

CS: Yes, definitely. I was a commercial HVAC [Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning] and plumbing insulator, so I would work on chilled water systems. And they have to be really tightly sealed and completely airtight or as soon as you turn on the system, the pipes are going to start sweating and you’ll cause hundreds of thousands of dollars in damage. So, it’s really high stakes. That was the biggest takeaway for me: Make sure you do your due diligence on the front end and you won’t have to run corrections and be completely embarrassed later.

And I learned about hard work. I mean, my construction job was really physically demanding work. And I did it for five years full time while I took the slow track on my undergrad degree. And it just taught me the value of hard work and made me really appreciate being able to work in a role that I feel like is a public service and helps the community to be informed.

NM: How about you, Michael? What was your path into journalism?

Michael Stavola: I always enjoyed telling stories. I was trying to pick a major in college and kept going back and forth between business and journalism. I have an uncle who used to be on the business side at the Ann Arbor News. He got me a summer internship at a paper out there in Michigan. I really only wrote one story of any substance that summer, but that experience and that story got me hooked.

I finished undergrad in 2013 and earned my MBA in 2020. I just kept seeing cuts in journalism and wanted to be able to have something to fall back on. I really just love learning though. I read stuff that is pretty mind-numbing to most people (and sometimes myself) but I just like learning new things. The MBA has helped in a few stories. I mostly cover breaking news, so it doesn’t come into play too often.

NM: Let’s talk about your series, particularly the first story of the series. How did it come about?

CS: This story was kind of two years in the making when we wrote it. We’d gotten some tips early on when the new director of Sedgwick County EMS, John Gallagher, was named. The employees were not happy with that selection. We didn’t exactly know why. So we kind of kept our ear out.

We also knew the handling of a death that was controversial, so in late March last year, the Kansas Board of EMS took some enforcement action against several first responders who were involved in that 2019 call.

The way our Kansas Board of Emergency Medical Services is structured here is their meetings are in Topeka [more than 130 miles away from Wichita]. They don’t post a lot of information online. What is posted does not have the department involved or the name of the employees on any other meeting minutes, so we could have foreseeably missed this story. But the Sedgwick County [EMS] put out a news release defending their employees, saying we’re aware of this action taken by the Kansas Board of EMS, and we’re prepared to defend our employees.

I immediately got on the phone and started making calls. And we ended up getting the investigative summary, which outlined the broken protocols and the horrific narrative behind this controversial call that has caused division in the department. And so, we reported that, and after we reported that it was immediately like the floodgates opened on the EMS employees who had been waiting to speak up and speak out for two years. I don’t know if they thought we weren’t interested in the story or what, but once that story broke, they all had to talk to us and tell us what was going on in their department.

And we just heard horror stories about the slow response times, the low morale, the number of really experienced paramedics who had left. And they were clear to us that this is not just a workforce issue. This is not like there’s a bunch of workers who are upset, but this is putting everyone’s life at risk in your community.

We dove right in, and I was just solely dedicated to this story for about three months, researching, getting documents, crunching data, building a database of our own and then interviewing as many EMS employees as possible. So, it all came together fairly quickly for as big of a story as it was, but we couldn’t have done it without those employees really stepping up and saying, “Enough is enough. We’re gonna to tell our hometown newspaper what’s going on in this department and in this community.”

NM: What was endangering people’s lives were slow EMS response times. You’ve quoted Gallagher in your story saying that there’s little evidence to tie response times to survival from heart attacks. But that’s untrue. How did you go about disproving his claim?

CS: I looked at old newspaper stories that looked at response times and kind of looked at how they did it. And some of the stronger pieces I saw were citing a medical journal study that I think may have been from 1996. Then I started looking at the American Heart Association and any EMS trade publications, and found a really recent study in the Journal of the American Heart Association, and it was conclusive that that the quicker an ambulance gets there, the better your chances of surviving when you have a cardiac arrest event or something else that’s really time sensitive.

I read 30 years’ worth of everything I could find that mentioned response times and outcomes. And it’s been long understood that for response times, the better they are, the better your outcomes for the patients.

As investigative reporters we’re really good researchers, but there are people who dedicate their lives to certain topics that we’re kind of parachuting in on.

And it’s not just medical stuff, but really any topic where you have experts, or alleged experts or officials saying one thing — and I mean, we saw a lot of that with the pandemic — people under political pressure or other things may have an incentive to downplay the seriousness of a situation or give misinformation or allow misinformation to stay out there if it benefits them. But there’s a lot of impartial research out there that gives you the facts outside of the political realm.

NM: What other documents did you use for your stories?

CS: Lots and lots of emails between county officials. Those were a really big part of the story because they showed in real time how county officials were responding to the crisis or not responding or pushing back against people who did have some questions and concerns. And we were able to show how county management’s response time was slow. For two years. They knew this for two years. They knew about this, but for two years they were in denial until they were confronted with this news story.

We also requested the EMS response time data from 2017 to 2021, both from 911 and the internal database maintained by Sedgwick County EMS, where they have a specific column titled “response time.” We were able to cross reference those two, build our own database and come up with the true response time that people could expect to wait for an ambulance. That was a lot of work.

Another thing we found out later was that when the EMS system is running low on ambulances, they put out a status advisory. We found out they were tracking how often they fell into critical status. They tracked and captured it in this system called MARVLIS [Mobile Area Routing and Vehicle Location Information System, pronounced “marvelous”]. We requested that data and it was really eye opening and jarring, because you could see how often they were just so under-covered here with ambulances. And to see that they were also aware of it because they were tracking it and still letting it get out of hand was really shocking.

But there was one part I wish we could have gotten. We were unable to find a good way to show how outcomes have changed [due to slow response times.] There doesn’t seem to be a good department-level or city- or county- or state-level or federal-level tracking of outcomes for 911 calls.

NM: You mentioned a database of response times from 911 calls and another from the Sedgwick County EMS. How did you match the two databases?

CS: Initially, we had timestamps. We were able to cross reference dates and times.

And then after I crunched all the numbers, we went to the county’s data guy who maintains this database and he eventually confirmed that my findings were indeed correct.

But an interesting development after we wrote this: In December, we checked back in and requested the same dataset for the entire year of 2021. The county is now redacting all of the dates and times claiming the HIPAA privacy rule.

NM: I wanted to go back to what you said earlier about the emails. You obtained thousands of emails. Sometimes government entities tack on a large price tag for big records requests. Did you have to pay for the documents?

CS: The way we were able to avoid a hefty price tag on this was we went straight to the record holder rather than going through the typical records custodian. So, say an elected official has all of these emails. You can go through their county legal [department] and file requests. But state law just requires you to submit it in written form. And the record holder, in my mind, is also a records custodian, so we went straight to the record holders and asked them for the documents in a written form. And we were able to receive them that way quickly — and probably not as heavily redacted.

NM: Did the elected officials try to resist your records requests?

CS: They did not. Even the ones who were kind of angry about us doing the story and had somewhat participated in the crisis and the events leading up to the crisis were still pretty open. When I would ask them for something, when they would make a statement or a claim, and I would say, “I need you to prove that to me,” they would shoot me over the emails that were related.

For some others, we had to go through the legal department, like Gallagher’s emails. He sent one email in particular that we actually received from a source. There was Gallagher basically warning the medical society that there was a story coming out and asking them not to pay any attention to it, because it’s just the same two reporters who were writing about him earlier. And he assured them that this too shall pass. That was the email that let me know that, OK, there’s no contrition here. There’s no regret, no remorse, just covering his ass.

NM: You feature two families in your first story. How did you find them?

CS: We asked some of the sources we built during this investigation, “What days were the worst?” That was when we tapped into that MARVLIS system. We requested all the 911 calls during the peak of the really bad times and listened to those and went and checked other records to see what the outcome was. Once we identified time and place, we could go find names, obituaries, things like that.

We were able to find two families. There were 11,000 calls but we were able to find these two that really I think show the problem and why [the situation] was so dangerous.

There was a lot of backgrounding and false leads. We took any and all information we could find and tried to triangulate them. We were successful in two cases and unsuccessful on dozens more that could have been equally horrific.

NM: Michael, you did a lot of the door-knocking to get the families to talk to you. What was that like?

MS: I had some EMS officials tell me about this call where an infant died. Those officials thought a better response time could have saved the child’s life. They were able to get a pulse from the 7-month-old but he later died. I knew we needed this for our story.

I think it was every Saturday (and a couple Fridays) for a month that I knocked on the door. I spoke with a couple of neighbors and left notes on the door each time. My notes were always gone when I came back so I knew they were receiving them. They live on a dead-end road. One Saturday, I left a note and went and turned around. As I passed back by the home, I saw the note wasn’t in the door anymore, so I knew they were home. I got out again and knocked. The father, in his 20s, started to cry and told me what happened.

I think you approach this by just by having empathy. I was convinced that if I could get in front of the family and tell them how important it was for me to tell their story, they would be willing to speak to me.

NM: So what happened to Dr. Gallagher?

CS: He’s no longer with the county. He accepted a settlement to resign which was less than what he was owed under the contract. And he’s no longer working at the local hospital. But he’s still in town. We’re keeping an eye on where he ends up. It does seem like someone will always hire a doctor.

NM: How quickly was he removed from his post after your stories ran?

CS: I think after the third story went into print, he was placed on administrative leave. And on the following Wednesday’s commission meeting, he accepted the resignation agreement settlement.

NM: That was quick!

CS: Yeah, but, the thing is, it felt like so long. We did write some more stories that week, after the three-part series ran. There was a timeline of the county’s mishandling of the EMS crisis. I wrote a reaction story from the local officials who said they’re really concerned. We ran a story on one family trying to raise enough money for a headstone. At least two more paramedics quit that week, because the county was taking so long to get rid of Gallagher after our stories ran. They wanted immediate action and they didn’t get it, so they quit. So, it was really fast looking back, but at the time it was like, “What are they doing? How can you read this and not do anything?”

NM: Have things improved at the county EMS since last July?

CS: Just from talking to EMS employees, morale is improving quite a bit. They now have an interim director who’s really well respected by the rank-and-file EMS workers.

Their response times have slightly improved. The rate with which paramedics are fleeing the county has stopped. I mean, that’s really stopped, and a couple paramedics have actually come back to work for the county after our reporting.

And two more big things have happened since our report. The Kansas Board of EMS has opened a departmental investigation of Sedgwick County EMS to see if they participated in any sort of malfeasance or cover up of the 2019 death. And the largest emergency room in the state, at Wesley Healthcare, has dropped their contract with the county and hired American Medical Response to do transports between its facilities. It’s several million dollars a year the county was getting from the hospital. The county is trying to challenge it. We don’t know what’s going to end up happening. But that’s several million dollars on the line that could further imperil the department from rebuilding.

Also, since our reporting, paramedics all received bonuses and COVID pay as essential workers. They started the signing bonus program, and they began paying for the education for EMTs to go to school to become paramedics and I believe they were able to do that because of the problems we were able to point out in our reporting.

NM: Michael, while working on the stories, what stood out to you the most?

MS: The amount of support we were getting from EMS employees. The county doesn’t allow them to speak with us, but they did anyway out of desperation. They tried to warn county officials about Dr. John Gallagher before they put him in charge of the department in 2019. They didn’t listen. They tried to tell county commissioners how bad things were getting. They also didn’t listen. County management also downplayed problems to the commissioners and the public. EMS employees love what they do and were willing to help us in any way they could, even at the cost of their job.

NM: What were the some of the biggest challenges of this project?

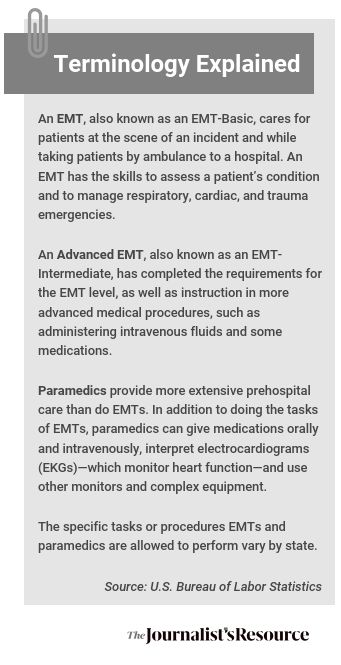

CS: We had a really steep learning curve on response times and the jargon, like what’s the difference between an EMT and a paramedic. They changed the configuration of the ambulances where they went from two paramedics per ambulance to one, and kind of by design. They designed it to lose a bunch of paramedics and backfill with much cheaper EMTs and each one of those people is qualified and trained in a different way. So just learning as much as we could about this was tough because it is kind of a specialty profession.

Another hurdle was just the way our local governments function here. All of their employees are instructed and directed to run any meeting requests or any interview requests or questions through the Strategic Communications Department. So, there’s just the chilling effect on employees that makes them not want to talk to us. Or, we would only get the scripted line if we go through Strategic Communications. But on this story, we were able to break through that and these employees were to a point with their employer, that it was more important for them to speak out than to avoid having a miserable experience at their job because they were already desperate. They were already ready to leave.

That’s a lot of pressure and we know how serious it is, because every day more paramedics were quitting and we can hear the call-outs over the police scanner where they’re saying we’re at ‘status zero’ or ‘status one’, meaning there’s zero ambulances or there’s one ambulance available for the entire county. And we knew we had to get this story out. But you also have to do the story right. So that was a constant stressor. And I challenged myself that if the EMS workers are putting in 12- and 14-hour days, I’m gonna put in 16-hour days. I worked some 16-hour, 20-hour days. This just became my life for three months. Around the clock, every waking second I was pretty much working on this.

One of the most stressful parts was that we came to really know some of these sources within the department, and we kept in good contact with them, and they would be extremely frustrated. A Saturday night or Friday night around here would just turn into pure chaos for them with the number of calls and the staffing shortages, and they would send us some text messages or call us really frustrated saying, “I really hope you guys are working hard on this. We just we put in 12-hour a day or a 14-hour day. Things just keep getting worse.” So that took a toll.

MS: [Another] challenge was the amount of information. We had 10-plus hours of interviews and secret records leaked to us, documents, emails and roughly 500,000 calls to filter through.

How did the story affect you? As a reader, I kept wondering why the local officials weren’t as worried about the EMS situation as you guys were as reporters.

CS: That crossed my mind several times. Like, why are we the only ones doing anything about it? And it makes you doubt yourself quite a bit. It makes you doubt all kinds of stuff. And then also the gaslighting from public officials makes you question your sanity, and just kind of the tunnel vision effect where you start getting into a story and you don’t see what else is happening because you’re just completely into the story. So yeah, it affected me greatly. Lots of stress, lots of anxiety of just wanting to get it right and making sure I wasn’t just wrong.

The director is the local expert, who you would usually turn to questions on EMS-related stuff, and he’s sitting here telling me that response times don’t matter and appropriate care was given, and all these things that are just so wildly out of step with common sense. It was kind of rough.

Luckily, Michael and I are both fairly young and we’re in good shape. We didn’t have any medical emergencies during this. But some readers and people we were in contact with had to call an ambulance or they have a family member who would get sick or would have something happen. And they would talk to us while we were reporting it, and say, “So I know you’re looking into this ambulance situation. If my loved one has a heart attack, should I just drive them to the hospital myself?” And I had to say, “Absolutely.” It was really sad.

I was also more keenly aware of ambulances around town. If I was driving to work, and I would see one, I would wonder if they’re running late right now. And then we have the police scanner going in our newsroom and you would hear “status one, status zero,” and your blood pressure would kind of go up and you’d hope there wouldn’t be some sort of a mass casualty event or a car wreck on the highway or something where people can’t get the help they need in time.

MS: It has reinvigorated my passion for journalism. I work the breaking news beat, which means there are a lot of loathsome news releases. I like people, I want to make a difference and that’s why I became a journalist. Knowing that our story has helped response times, which I am confident has and continues to save lives, warms my soul. I think about it often as I sit in the office and listen to the police scanner and hear calls for help.

NM: What’s your advice for reporters, especially local reporters?

CS: Don’t give up. Don’t get discouraged and keep fighting for answers until you get to the bottom of things. We are in a really closed system [in Kansas], and I assume it’s like this in a lot of midsize and smaller cities and even larger cities where the hometown newspaper is maybe the last line of defense from serious government neglect or malfeasance or public health crisis. It’s important to take that job seriously and to try to hold accountable everyone in local government.

A lot of people don’t pay much attention to what happens in city hall or the county courthouse or with some of our local leaders, but man, it sure is important if you call 911 and an ambulance doesn’t show up until after your loved one’s already dead. You know that the attention needs to be there, and local news could be the only way to get the attention on these important issues.

MS: Keep chipping away. Your work matters. It’s important. It can save lives. Look at the daily stories as a necessary part of being able to tell those bigger stories. Some of those daily stories you may not want to do, but you never know how that feel-good feature or covering the tragic death of a loved one could lead to an important source that helps you in the future.

Read the stories

- You can read the entire series here. Some of the stories are behind a paywall.

- Unresponsive: Crisis at Sedgwick County EMS leaves many waiting for life-saving care

- County EMS workers disillusioned, say relationship with leaders too broken to fix

- Sedgwick County leaders disregarded warnings by EMS workers from the beginning

- Video: Timeline of the EMS crisis

- With removal of Sedgwick County EMS director John Gallagher, manager Stolz seeks changes

- EMS Director Dr. John Gallagher resigns; Sedgwick County to pay him $85,000

- Kansas state board opens investigation into Sedgwick County EMS handling of patient

- State board asks for probe of EMS leader after man left to die in Wichita apartment

Expert Commentary