As is the case in many U.S. cities, majority Black neighborhoods in Pittsburgh have a lower average life expectancy than majority white neighborhoods. New research links this disparity to property tax delinquency.

The study shows that in the city’s poor, predominantly Black neighborhoods, where life expectancy is lower, property tax delinquency is higher compared with poor, predominantly white neighborhoods.

This association has its roots in America’s history of racism and segregation that have had long-lasting impacts on communities of color, the researchers explain.

“[Tax delinquency] is capturing lack of investment in the neighborhood and lack of commercial or infrastructure vibrancy and, in general, long-term distress that the neighborhood has been experiencing, which can be tied to health outcomes,” says study co-author Anita Zuberi, an assistant professor in the Department of Sociology at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh.

Although the new research is specific to Pittsburgh and may not be generalizable, the findings are broadly relevant because many cities in the U.S. remain segregated by race and income, according to the authors of “Death and Taxes: Examining the Racial Inequality in Premature Death Across Neighborhoods,” published in the Journal of Community Psychology in July.

The study adds to a growing body of research showing that a neighborhood’s impact on its residents needs to be considered in a more nuanced way than just focusing on factors like their health status, income, employment rate or education level. Tax delinquency is an indicator of commercial properties or houses that have been left vacant or neglected.

The study underscores the argument that historical residential segregation of Black people in the U.S., such as redlining, is a fundamental determinant of health and the persistent racial inequality in health outcomes, write study authors, Zuberi and Samantha Teixeira.

“The fact that people’s life expectancy is tied to the neighborhood in which they live, and is dictated by historic legacies of racism that get under the skin to shape life outcomes, is an injustice of epic proportions,” they write.

Impact of tax delinquency on neighborhoods

In Zuberi and Teixeira’s study, tax delinquency captures the percent of each neighborhood’s homes and commercial properties where the taxes have not been paid for at least one year. Some, but not all, tax delinquent properties may be vacant or abandoned.

Tax delinquency may be an indication of new generations of residents abandoning poor neighborhoods for better opportunities or residents not paying taxes on properties in undesirable areas of the city, Zuberi and colleagues explain in a previous study.

The 2016 study “Neighborhoods, Race, and Health: Examining the Relationship Between Neighborhood Distress and Birth Outcomes in Pittsburgh,” published in the Journal and Urban Affairs, is one of the first studies to explore the relationship between a neighborhood’s tax delinquency and health outcomes, including preterm birth.

In that paper, Zuberi and her colleagues, Waverly Duck, Robert Gradeck and Richard Hopkinson, show that tax delinquency might reflect high levels of physical abandonment such as vacant housing and land, the proliferation of crime, and a general disinvestment in community services, all of which are associated with public health. They find that “high levels of tax delinquency may symbolize a loss of hope within the neighborhood, leading to increased stress and adverse behaviors among mothers that can affect birth outcomes.”

A few other researchers have also looked at the impact of other tax-related measures, such as home foreclosures on health outcomes.

In the 2019 study “Neighborhood Tax Foreclosures, Educational Attainment, and Preterm Birth among Urban African American Women,” published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Dawn Misra and Shawnita Sealy-Jefferson build on Zuberi’s 2016 study and explore the relationship between home foreclosures and birth outcomes among Black women in Detroit.

Overall, they don’t find a statistically significant association between the number of foreclosures in a neighborhood and the risk of preterm birth among Black women, but they find that women’s level of education does make a difference. For Black women with more than 12 years of education, the risk of preterm birth was significantly lower statistically, suggesting that education may have a buffering effect, partly because it shapes job prospects and is associated with more compliance with health recommendations during pregnancy, Misra and Sealy-Jefferson write.

“The important message is that a lot of times we try to look very broadly at these issues and we don’t realize that there are some subgroups where something might be particularly harmful [while] in other groups it doesn’t harm them as much,” says Misra, a professor and chair of the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at Michigan State University.

There are multiple dimensions of the neighborhood environment “and we still are probably at a pretty early stage trying to figure out what comes first and what problem is important,” says Misra.

Impact of neighborhood disadvantage

Concentrated poverty and socioeconomic disadvantage in racially segregated neighborhoods are a fundamental reason for poorer health outcomes, Zuberi and Teixeira write.

Research has shown that physical and social aspects of a neighborhood can influence residents’ behavior and stress levels.

In the 2012 study “Health Status, Neighborhood Socioeconomic Context, and Premature Mortality in the United States: The National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study,” published in the American Journal of Public Health, researchers find poor neighborhood socioeconomic conditions affect how long healthy people live — an impact beyond an individual’s demographics, education level or lifestyle.

Studies have also shown residential segregation is among the main drivers of racial health disparities.

In “Is Racism a Fundamental Cause of Inequalities in Health?” published in the Annual Review of Sociology in 2015, the authors conclude that “racial inequalities in health endure primarily because racism is a fundamental cause of racial differences in socioeconomic status and because socioeconomic status is a fundamental cause of health inequalities.”

Studies have also shown that giving people the opportunity to move to neighborhoods that have a lower poverty rate may improve their health.

Several studies on the Moving To Opportunity project, conducted by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development between 1994 and 1998, find a link between the ability to move from a high-poverty neighborhood to a low-poverty neighborhood and improvements in physical and mental health for families. High-poverty neighborhoods had 40% or more residents with incomes below the federal poverty line and low-poverty neighborhoods had 10% or fewer residents with incomes below the federal poverty level.

Moving to lower-poverty neighborhoods was also associated with improved college attendance rates and earnings for children who were younger than 13 years old when their families moved, researchers show.

A long-term follow up study on the Moving To Opportunity project found that moving to a neighborhood with a lower level of poverty was associated with “modest but potentially important” reductions in the prevalence of extreme obesity and diabetes among the participants in the project, even though the underlying mechanism was unclear.

“So it really allowed us to start thinking in a more nuanced way about what it is in the neighborhood in addition to poverty that matters for health,” says Zuberi.

Impact of neighborhood abandonment

Neighborhood abandonment has physical features, such as vacant buildings and lands, and social features, such as violent crime, low sale price of properties and failure to pay property taxes. Together, these factors may isolate residents in their homes, exacerbate crime and drug abuse and sales, which have a direct relationship with health and death of residents, the authors write.

In addition to Zuberi and Teixeira’s study, other studies have shown that physical and social abandonment in neighborhoods is linked to poorer health and early death of residents.

The 2003 study “Neighborhood Physical Conditions and Health,” published in the American Journal of Public Health, shows boarded-up housing may be related to risk of early death.

“Areas with boarded-up housing are usually considered dangerous and thus generate fear among residents and outsiders alike, thus contributing to social isolation,” the authors write. “Fewer commercial businesses may be conveniently accessible, either as a result of lower demand or because fearful business owners would prefer to locate elsewhere.”

As a result, residents of these neighborhoods are less likely to have access to nutritious food or outdoor exercise, the authors of the 2003 study write, finding that boarded-up housing was a predictor of premature death before age 65.

Research has shown that a thriving commercial district provides residents with social connections and a broader network of services, and in some cases, might mean the difference between life and death. The lack of such resources may mean that people are to deal with neighborhood and life stressors alone and may lead to premature death. It might also be that individuals left to live in abandoned neighborhoods already suffer from health issues, increasing their chances of dying young. More likely, it’s the combination of two, Zuberi and Teixeira write.

In his 2015 book Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago, Eric Klinenberg explores why some poor neighborhoods that were heavily Black had more deaths due a heat wave in July 1995. As Zuberi and colleagues point out in their study, Klinenberg writes the large number of vacant buildings and land, coupled with high levels of crime, contributed to “social isolation so great that many elderly individuals died alone in apartments where windows were shut and doors were locked.” In contrast, in majority Latino neighborhoods in Chicago at the time, there was more infrastructure, so people could come out of their homes, go into a store, cool down and be socially connected.

Methodology and detailed findings of the “Death and Taxes” study

Zuberi and Teixeira set out to explore the intersection of neighborhood race and premature death and examine the importance of neighborhood abandonment in this relationship.

This new paper builds on their previous work that examines the relationship between neighborhood distress and birth outcomes in Pittsburgh.

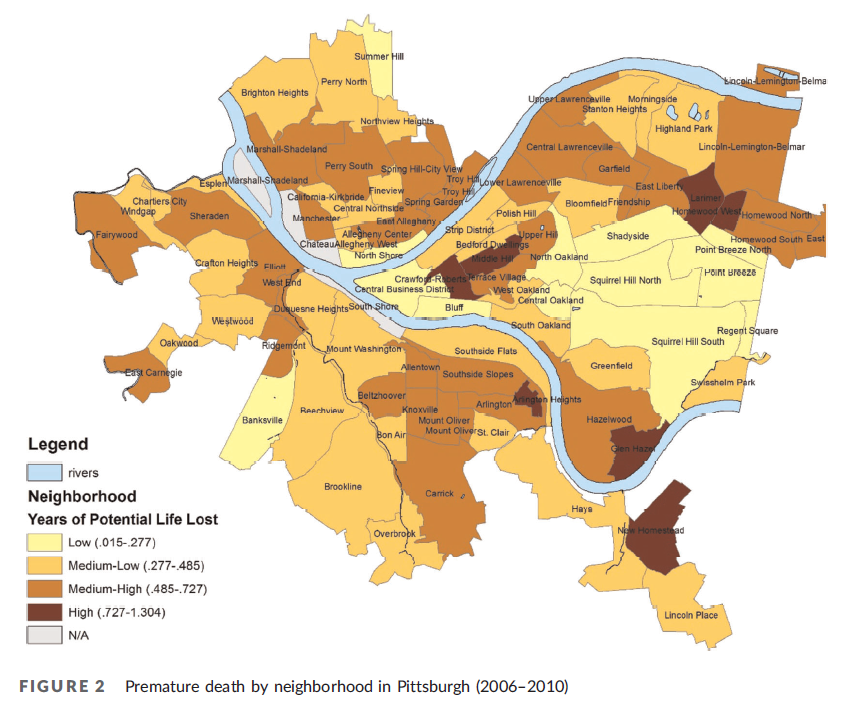

They chose Pittsburgh because the city’s population has declined substantially since the 1950s and has a long history of residential segregation by race. The city has 90 distinct neighborhoods, which allowed researchers to explore variations across the city. In 25 neighborhoods 50% or more of residents identified as Black. In 62, less than 50% identified as Black.

Researchers combined the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey data collected from 2005 to 2009 with data from the city of Pittsburgh to examine differences in premature death in 87 neighborhoods.

They excluded three neighborhoods either because the populations were too small or they lacked data on housing conditions.

The researchers chose to focus on the years 2005 to 2009 because census tract boundaries in Pittsburgh changed between 2009 and 2010 and no longer matched the city’s neighborhood boundaries, making it more challenging to analyze the data.

For their analysis, Zuberi and Teixeira used common measures of socioeconomic disadvantage, such as the poverty rate, percentage of unemployed residents and average adult education levels. They also included less studied neighborhood features such as vacancy, property tax delinquency and property sales and conditions. They calculated tax delinquency as the percent of all taxable parcels that are delinquent on city and school district taxes for at least one year.

“I think it’s a very creative way of looking to find out more than just what the median income is in the neighborhood or the crime rate is in neighborhood,” says Misra. “It’s really looking at the actual conditions of housing.”

Not all poor individuals live in poor neighborhoods, the authors note. But Black residents — poor or not — are far more likely to live in high-poverty neighborhoods. (The authors define high-poverty neighborhoods as where more than 30% of the residents live below the federal poverty line.)

In Pittsburgh, more than 1 in 4 people who are poor and Black live in high-poverty neighborhoods compared with 1 in 13 of their white counterparts, the authors write.

Many poor white individuals “don’t have the double disadvantage that many poor Black families are facing,” of being poor and living in a high-poverty neighborhood, says Zuberi.

In their analysis, Zuberi and Teixeira also find that the percentage of Black people living in a neighborhood is associated with the premature death rate. More specifically, they show that race is more strongly tied to the level of premature death in Pittsburgh neighborhoods than socioeconomic disadvantage measures such as poverty rate.

Researchers define “premature death” as dying before age 75, the average age of death in the U.S and most developed countries.

However, they note that race is a fundamental predictor of health and death “not because of differences in biology but due to social experiences including racism and segregation.”

Their research shows that majority Black neighborhoods had significantly higher levels of every variable examined. Poverty levels were twice as high in majority Black neighborhoods compared with majority white neighborhoods, so were the rates of violent crime. Also, the share of housing units in poor condition were 1.8 times as high, the share of vacant land was 2.5 times as high and the share of vacant housing units was 1.7 as high. The average property sale price was nearly $64,000 lower.

The share of land parcels that were tax delinquent was three times higher in majority Black neighborhoods than white neighborhoods — 41% versus 15.1%. Meanwhile, years of potential life lost among residents in majority Black neighborhoods was 36% higher than in white neighborhoods.

“In addition to visual symbols of urban decay, latent features of abandonment like tax delinquency that represent divestment in predominantly Black neighborhoods exist and still exert their effects decades after we have formally ended segregation,” the authors write.

Possible solutions

The study has potential policy implications.

“A lot of places in Pittsburgh where we see the highest levels of tax delinquency were once neighborhoods that were very vibrant communities, but over time have really shifted and have lost populations,” says Zuberi. “One of the things that the tax delinquency suggests is that it’s not just about addressing the health downstream but also thinking upstream about what we can do to help support and improve the health of these neighborhoods to become more vibrant places over time.”

Zuberi and Teixeira point to a growing body of research that suggests engaging residents in vacant-lot greening and reclamation might reduce gun crimes and serious violence in the surrounding area.

“Understanding what factors, in addition to poverty, play a role in the relationship between premature death and neighborhood race helps to inform the design of programs and policies to reduce spatial inequality by improving the environments in which people live,” they write.

They also call for more research.

Other cities could pool their administrative records to examine features related to abandonment — especially tax delinquency — to see how they relate to race and premature death.

Analyzing data on the social infrastructure in the neighborhood, such as commercial properties and libraries and the neighborhood’s level of tax delinquency could help unpack the relationship between death and taxes. It also would be helpful to examine the causes of death in a neighborhood and make comparisons across neighborhoods by race, the authors write.

The study’s limitations

The authors obtained most of their data from local administrative records rather than national sources such as the U.S. Census Bureau. Because the data apply only to certain neighborhoods in Pittsburgh, the results may not be generalizable to other parts of the U.S.

The data also doesn’t separate the impact of individual-level health characteristics from the impact of the neighborhood on premature death.

In addition, the authors’ measure of potential years of life lost in terms of premature death doesn’t specify the causes of death, so the authors can’t say with certainty the mechanisms that explain how the percentage of tax delinquent parcels is tied to premature death.

Additional reading

Stuck in Place: Urban Neighborhoods and the End of Progress Toward Racial Equality Patrick Sharkey, April 2013.

Neighborhood and Health Ana V. Diez Roux and Christina Mair, Annals of The New York Academy of Science, February 2010.

Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, Maggie R. Jones, Sonya R. Porter, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, December 2019.

The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America Richard Rothstein, May 2017.

Places For the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life Eric Klinenberg, Sept. 2019.

More about taxes and abandoned buildings from The Journalist’s Resource

Property Taxes 101: A primer for journalists

U.S. property taxes: Comparing residential and commercial rates

How racial and ethnic biases are baked into the U.S. tax system

Zombie property: What research says about abandoned buildings

Expert Commentary