This piece about pulse oximeters was updated on Nov. 11, 2022, with information about the latest FDA hearing.

Pulse oximeters are small medical devices that clip on the fingertips and estimate the amount of oxygen in the blood. They are ubiquitous in doctors’ offices and hospitals and became popular during the pandemic as a way for people battling COVID-19 to monitor their oxygen levels at home.

Developed in the 1970s, pulse oximetry has been integrated into the routine monitoring of hospitalized patients and has become a fundamental tool in diagnosis and treatment of patients, especially those with respiratory illnesses. The devices have taken an even more significant role in hospitals since the COVID-19 pandemic began.

“For COVID, we became so dependent on pulse oximeters for [patient] triage,” says Dr. Theodore Iwashyna, an intensive care unit physician and senior author of a recent study on pulse oximeters in The BMJ. In addition, the readings from devices became critical in helping doctors decide which hospital patients were eligible for COVID-19 medication like remdesivir.

But a series of recent studies have found that pulse oximeters are more likely to give inaccurate readings for people with darker skin, especially Black people, by overestimating their blood oxygen levels. This is particularly important for critically ill patients, where doctors constantly rely on pulse oximeter readings to decide how much oxygen to give patients.

Unrecognized low blood oxygen levels can damage organs, most importantly the brain and the kidneys. Some studies that include data from COVID-19 patients suggest that inaccurate readings by pulse oximeters may be associated with worse outcomes for Black and Hispanic patients.

This is not the first time researchers have brought up the issue. Problems with pulse oximeters have been recorded since the late 1980s but those problems resurfaced as the pandemic spurred more use of the device and highlighted existing racial disparities in health care.

Researchers say today’s pulse oximeters aren’t calibrated to account for darker skin, because they’re built on data from mostly light-skinned, healthy study populations whose diversity doesn’t reflect that of the overall U.S. population.

Some manufacturers of pulse oximeters have asserted that their devices are accurate. But if their data doesn’t show a problem, “then how do [they] explain why this problem keeps showing up in critically ill patients?” asks Iwashyna, professor of medicine and public health at Johns Hopkins University. “There’s a role for journalists to keep asking the companies to comment on this and explain it.”

Dr. Eric Gottlieb, lecturer at the Laboratory for Computational Physiology at MIT and lead author of another study on pulse oximetry, also encourages journalists “to spread the word and raise awareness about” disparities in pulse oximetry readings.

During his research, Gottlieb was asked frequently what patients and physicians should know about the findings and whether they should consider them in their medical decision making, he says.

“And my response has been yes, I want them to know about it and be aware, but I think it’s really difficult to put the onus on either the patient or the physicians,” says Gottlieb. “I think this really puts the onus on the manufacturers, institutions and the government to really ensure that these devices are used equitably.”

In a safety communication in February 2021, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration referenced a 2020 study and said the pulse oximeters’ accuracy may be affected by several factors including skin pigmentation. In June, the agency announced in June plans to convene a public meeting to discuss the available evidence on the accuracy of pulse oximeters. And in November, an expert panel urged the agency to improve its accuracy standards and the testing of the devices.

How pulse oximeters work

Blood oxygen levels are calculated in percentages. Generally, in healthy people, a blood oxygen level between 95% and 100% are considered normal, but the level varies for people who have chronic lung conditions such as asthma. In most people, blood oxygen levels below 88% require medical attention.

“Once you get below 88%, we start freaking out very quickly because it has a big impact on how much oxygen is getting to your tissues,” says Iwashyna.

There are two ways to measure the level of oxygen in the blood. The most accurate method is through a blood draw from an artery, usually in the wrist, which can be painful. The other method is pulse oximetry.

Medical professionals in hospitals depend on pulse oximeter readings because they are done in seconds, while it can take up to an hour for the results of an arterial blood sample to become available.

Pulse oximeters work by shining infrared and red lights through the skin. The devices then calculate the amount of light absorbed by hemoglobin — proteins inside red blood cells that carry oxygen from the lungs to tissues and organs.

“So it’s taking advantage of the fact that the light gets absorbed differently when the hemoglobin has oxygen on it versus when it doesn’t,” says Iwashyna.

Researchers haven’t exactly pinpointed why pulse oximeters are more likely to give inaccurate readings in people with darker skin, but one hypothesis is that some of the device’s light might be absorbed by melanin in the skin. Melanin is the substance that produces skin, eye and hair pigmentation. People with darker skin have more melanin.

Although skin tone is a predominant suspected factor affecting pulse oximetry readings, other factors may also play a role.

“I think it’s important to not make assumptions and really explore blood chemistry and other factors like differences by age and gender that can have effects as well,” said Gottlieb.

Errors in pulse oximeter readings can also be caused by motions such as shivering, interfering substances in the blood, misplacement, and low blood circulation. Even nail polish can affect the device’s readings.

“They mostly work,” says Iwashyna. “They just don’t work a lot and the times that they don’t work a lot happens more in Black patients.”

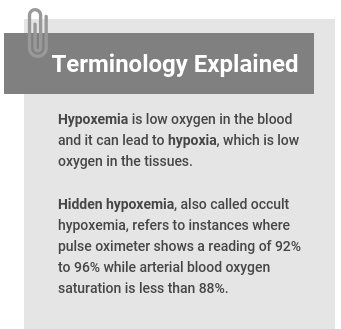

Below, we have gathered several studies that show the problem of racial bias in pulse oximetry. In most instances, researchers compare pulse oximetry readings with the results of arterial blood draw, usually done within 10 minutes of each other, to find out how accurate the devices’ readings are. And the most common condition they look for is hidden hypoxemia — also called occult hypoxemia — which is typically when a pulse oximeter shows a reading of 92% to 96% while arterial blood oxygen saturation is less than 88%.

Research roundup

Racial Bias and Reproducibility in Pulse Oximetry among Medical and Surgical Inpatients in General Care in the Veterans Health Administration 2013-19: Multicenter, Retrospective Cohort Study

Valeria S. M. Valbuena; et al. The BMJ, July 2022.

The study: Researchers tested the discrepancies between pulse oximetry readings and arterial blood draw results among hospital patients. Previous studies have shown pulse oximetry’s racial bias in patients in intensive care units. The authors of this study wanted to see if the bias extended to hospital patients not in intensive care. Specifically, researchers wanted to find out how often pulse oximetry misses low blood oxygen, or hypoxemia, in Black patients.

The study looked at 30,039 pairs of pulse oximeter readings and results from arterial draws done within 10 minutes of each other among patients at 100 hospitals in the U.S. Veterans Health Administration, from 2013 to 2019. Seventy-three percent of the patients were white, 21.6% were Black and 5.4% were Hispanic or Latino.

Key findings: The analysis showed that Black patients had higher odds of having low blood oxygen that was not detected by pulse oximetry compared with white patients. When the pulse ox showed the patient’s blood oxygen saturation at 92% or higher, which is considered fine, the arterial draw showed oxygen levels less than 88%, which is considered dangerous. The probability of undetected low blood oxygen using a pulse oximeter was 15.6% in white veterans, 19.6% in Black veterans and 16.2% in Hispanic or Latino veterans. “This difference could limit access to supplemental oxygen and other more intensive support and treatments for Black patients,” the authors write.

The analysis also shows that in patients who had two paired readings of pulse ox and blood samples, one pair done earlier in the day and one pair later, the readings were less likely to be consistent between morning and evening among Black patients compared with white patients, making pulse oximeters a less reliable source of estimating the patients’ blood oxygen saturation.

Key takeaways: The researchers estimate that 573,000 Black patients in the VA system might have had undetected hypoxemia during the study period — roughly 80,000 patients a year – which could have been detected if the devices worked as well as they do in white patients. “Large integrated health systems such as the Veterans Health Administration and NHS could have a role to purchase and use only pulse oximeters proven to provide equivalent accuracy in Black patients rather than devices of unproven equity,” they write.

Assessment of Racial and Ethnic Differences in Oxygen Supplementation Among Patients in the Intensive Care Unit

Eric Raphael Gottlieb; et al. JAMA Internal Medicine, July 2022.

The study: The researchers wanted to know if racial and ethnic disparities in the administration of supplemental oxygen in an intensive care unit in Boston were associated with discrepancies in pulse oximeter readings. The study included 3,069 patients admitted to the ICU for at least 12 hours before needing advanced respiratory support, from 2008 to 2019. Eighty seven percent of the patients were white, 6.7% Black, 3.6% Hispanic and 2.7% Asian.

The authors used data from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care critical care data set (MIMIC-IV), which includes patients admitted to the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. Instead of analyzing data from specific points in time, they averaged oxygenation levels and flow rates from nasal cannulas for up to 5 days from ICU admission or until the patients were intubated or received more advanced respiratory support.

Key findings: Asian, Black and Hispanic patients had higher pulse oximetry readings for a given oxygen saturation obtained from a blood sample and were given significantly less supplemental oxygen compared with white patients. When low levels of oxygen are undetected — hidden hypoxemia — patients are at a higher risk of worse outcomes, including higher death rates. These differences may contribute to racial and ethnic disparities in outcomes, including during the COVID-19 pandemic, the authors write.

Key takeaway: The authors note that the study doesn’t show the causal association of disparities in outcomes and differences in oxygen supplementation, but “the finding that race and ethnicity could affect how much oxygen a patient receives is notable and concerning,” they write. “Our findings present a unique and compelling opportunity to improve equity through device reengineering and by reevaluating how data are interpreted. However, this should be done with caution, as some past attempts to correct for race and ethnicity in algorithms have exacerbated disparities and are subject to ethical concerns.”

In an accompanying editorial, Drs. Eric Ward and Mitchell Katz write: “Health care systems, including academic centers, are large-scale purchasers of pulse oximeters. If they make a commitment to buy only devices that function across skin tones, manufacturers would respond.”

Racial and Ethnic Discrepancy in Pulse Oximetry and Delayed Identification of Treatment Eligibility Among Patients With COVID-19

Ashraf Fawzy; et al. JAMA Internal Medicine, May 2022.

The study: The researchers wanted to find out if there are racial and ethnic biases in pulse oximetry among COVID-19 patients and whether there is an association between those potential biases and unrecognized or delayed oxygen administration. They analyzed data for 7,126 COVID-19 patients from five hospitals in the Johns Hopkins Health System. About 38% of the patients were white, 39.3% were Black, 17.7% were Hispanic and 5.2% were Asian.

Compared with white patients, pulse oximeters overestimated oxygen levels by an average of 1.7% in Asian patients, 1.2% in Black patients and 1.1% in Hispanic patients, they found.

In a subgroup of 1,903 patients, Black patients were 29% less likely than white patients to have their eligibility for oxygen treatment recognized by the pulse oximeters. For about a quarter of patients in this subgroup, the device never recognized their eligibility for oxygen treatment. More than half of those patients were Black.

Key findings: The overestimation of blood oxygen by pulse oximeters was associated with “a systematic failure to identify Black and Hispanic patients who were qualified to receive COVID-19 therapy and a statistically significant delay in recognizing the guideline-recommended threshold for initiation of therapy,” the researchers write.

Key takeaway: Inaccuracies in pulse oximetry readings among racial and ethnic minority patients should be examined as a potential explanation for disparities in COVID-19 outcomes, the authors write.

In an accompanying editorial, Drs. Valeria Valbuena, Raina Merchant and Catherine Hough write: “The economics associated with ignoring the issue cannot be excluded from this discussion. Hospitals and practitioners continue to buy and use these devices despite their inaccuracy for non-White patients. The observation that designing a new device and exchanging millions of machines in hospitals and clinics across the country may be deemed unpopular could suggest that racial equity in patient care is not something these institutions are willing to pay for — or at least not enough of a priority to insist on devices that work equitably.”

Analysis of Discrepancies between Pulse Oximetry and Arterial Oxygen Saturation Measurements by Race and Ethnicity and Association with Organ Dysfunction and Mortality

An-Kwok Ian Wong; et al. JAMA Network Open, November 2021.

The study: The researchers investigated whether pulse oximetry readings, hidden low blood oxygen (occult hypoxemia) and clinical outcomes differed among racial and ethnic groups. They used five databases with a total of 87,971 patients from 215 hospitals and 382 intensive care units in the U.S.

Key findings: Discrepancies in pulse oximetry accuracy among racial and ethnic minorities were associated with higher rates of hidden hypoxemia, death and organ dysfunction. Although pulse oximeter readings missed low blood oxygen levels in all racial and ethnic groups, the incidence was highest in Black patients (6.9%) and Hispanic patients (6%), compared with Asian patients (4.9%) and white patients (4.9%). Patients with hidden hypoxemia were more likely to experience organ dysfunction or die in the hospital.

Key takeaway: “The important message is that health care devices, like predictive algorithms and medications, must be designed more inclusively to achieve comparable measurement accuracy irrespective of race and ethnicity,” the authors write. “It is important to be cognizant of the patient population in which pulse oximeters used in critical care are validated. There is a need for more transparency in the labeling of all patient care devices, including the detailed characteristics of groups on which they were evaluated. To further achieve more equitable health outcomes, we call for reinforced testing and recalibration of health care devices — across all target patient populations.”

Also read this opinion piece, “The accuracy of pulse oximeters shouldn’t depend on a person’s skin color,” by the study’s lead author, Dr. A. Ian Wong, published in STAT in July 2022.

Racial Bias in Pulse Oximetry Measurement

Michael W. Sjoding; et al. The New England Journal of Medicine, December 2020.

The study: Published during the early months of the pandemic, the authors investigated the clinical significance of potential racial bias in pulse oximetry measurement. The study involved 1,333 white patients and 276 Black patients at the University of Michigan Hospital from January to July 2020, and 7,342 white patients and 1,050 Black patients in intensive care units at 178 hospitals from 2014 through 2015. Researchers compared pulse oximetry readings and oxygen levels from arterial blood samples, done within 10 minutes of each other. They analyzed the results for hidden hypoxemia, which occurs when arterial oxygen saturation is less than 88% even though a pulse oximeter shows 92% to 96% saturation.

The findings: The analysis shows that in the University of Michigan cohort, 11.7% of Black patients had hidden hypoxemia compared with 3.6% of white patients. In the multicenter cohort, 17% of Black patients had hidden hypoxemia compared with 6.2% of white patients. “Thus, in two large cohorts, Black patients had nearly three times the frequency of occult hypoxemia that was not detected by pulse oximetry as white patients,” the authors write.

Key takeaway: “Our results suggest that reliance on pulse oximetry to triage patients and adjust supplemental oxygen levels may place Black patients at increased risk for hypoxemia. It is important to note that not all Black patients who had a pulse oximetry value of 92% to 96% had occult hypoxemia,” the authors write. “Our findings highlight an ongoing need to understand and correct racial bias in pulse oximetry and other forms of medical technology.”

Additional studies

- “Reliability of Pulse Oximetry in Titrating Supplemental Oxygen Therapy in Ventilator-Dependent Patients,” published in CHEST in June 1990, is among the first studies showing that pulse oximetry readings were less reliable in Black patients compared with white patients.

- “Racial Bias in Pulse Oximetry Measurement Among Patients About to Undergo Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in 2019-2020: A Retrospective Cohort Study,” published in CHEST in April 2022, finds that the rate of hidden hypoxemia was 21.5% in Black patients and 8.6% in Hispanic patients, compared with 10.2% in white patients and 9.2% in Asian patients, all of whom had had their oxygen reading 6 hours before they were given extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO, which is a life support machine.

- “Pulse Oximeter Measurements Vary across Ethnic Groups: An Observational Study in Patients with COVID-19,” published in the European Respiratory Journal in April 2022, shows that false readings by pulse oximeters were nearly 6.9% higher than the levels obtained from an arterial blood samples in patients of mixed ethnicity with COVID-19, compared with 5.4% in Black patients, 5.1% in Asian patients and 3.2% in white patients.

- “Pulse Oximetry for Monitoring Patients with Covid-19 at Home — A Pragmatic, Randomized Trial,” published in the New England Journal of Medicine in May 2022, finds that compared with remotely monitoring patients’ shortness of breath with automated check-ins, the addition of pulse oximetry did not save more lives or keep more people out of the hospital.

- “Self-reported Race/Ethnicity and Intraoperative Occult Hypoxemia: A Retrospective Cohort Study,” published in Anesthesiology in May 2022, finds prevalence of hidden hypoxemia was significantly higher in Black patients (2.1%) and Hispanic patients (1.8%), compared with white patients (1.1%). Also read the study’s accompanying editorial.

- “Racial Disparities in Occult Hypoxemia and Clinically Based Mitigation Strategies to Apply in Advance of Technological Advancements,” published in Respiratory Care in June 2022, finds the frequency of hidden hypoxemia was 7.9% in Black patients compared with 2.9% in white patients.

- “Critical Care Trainees Call for Pulse Oximetry Reform,” published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine in March 2021, calls on regulatory bodies in the U.S., U.K. and Europe to “to conduct an immediate review of the accuracy of pulse oximeters in patients of color and to only approve oximeters that are proven to perform equivalently in White patients and patients of color in the clinically relevant range of 88% – 96%.”

- “Racial Discrepancy in Pulse Oximeter Accuracy in Preterm Infants,” published in the Journal of Perinatology in October 2021, finds a modest but consistent difference in pulse oximetry reading errors between Black and white infants, with increased incidence of hidden hypoxemia in Black infants.

More on pulse oximeters

- “How a Popular Medical Device Encodes Racial Bias,” published in Boston Review in August 2020 by Amy Moran-Thomas, an associate professor of anthropology at MIT, delves deep into the history of pulse oximeters and explores the current research and conversations on racial bias in pulse oximetry results. Moran-Thomas wrote another in-depth article, “Oximeters Used to Be Designed for Equity. What Happened?” in Wired in June 2021.

- “Pulse Oximetry: Understanding its Basic Principles Facilitates Appreciation of its Limitations,” published in Respiratory Medicine in June 2013, is an in-depth technical paper on how the device works.

- “When it comes to darker skin, pulse oximeters fall short,” by Craig Lemoult of WGBH News, offers a series of solutions in the works to address the shortfalls of current pulse oximeters. Researchers are experimenting with devices that use polarized light, which isn’t absorbed by skin pigmentation, or measure the person’s skin tone, he reports.

Expert Commentary