Update 1: On Sept. 19, 2022, this research roundup about mpox was updated with a new study added under the “Additional research” subhead.

Update 2: On Aug. 14, 2024, this article was updated with more research studies and the CDC’s latest alert to health care providers, and WHO’s declaration of a global emergency.

Human mpox, an infectious disease caused by the mpox virus, was first discovered 70 years ago. The virus has been present in parts of Central and West Africa, as a result of animal-to-human and human-to-human transmission.

In recent years, a handful of researchers who study the virus tried to notify the international community about a brewing problem, but their reports went mostly unnoticed until an outbreak in the United Kingdom in May 2022, which was the beginning of an outbreak in several countries, including the U.S. By September 2022, the outbreak had spread to more than 90 countries.

The number of mpox infections declined in the following months, and so did news stories. But almost two years later, the threat of mpox has returned with a deadlier version of the disease, which has spread from the Democratic Republic of Congo to other African nations. This version of mpox has not been reported outside of central and eastern Africa as of summer 2024, but in August the CDC issued an alert to health providers to be on the lookout for suspected cases of mpox among their patients, especially those who have traveled to the affected regions. African health officials declared a public health emergency, days before the World Health Organization declared mpox a global health emergency on August 14, 2024. This is the second time in two years WHO has declared a global health emergency for mpox.

Meanwhile, a recent survey by the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania finds that knowledge about mpox has declined, following an increase between July and August 2022, and so has the fear of the disease.

To help journalists with their continued reporting, we’ve gathered several key facts and peer-reviewed studies on mpox. As you will see in the collection of studies below, scientists have been sounding the alarm for years leading up to the 2022 outbreak, calling for more research and better surveillance. We’ll update this piece regularly as new information and research come to light.

First, let’s begin with the basics.

The name: The virus and the infection were called monkeypox until November 2022, when the World Health Organization changed the name to mpox, phasing out the term monkeypox.

WHO renamed the virus after calls by many groups, including a letter signed by 22 scientists in June 2022 calling for an “urgent need for non-discriminatory and non-stigmatizing nomenclature.”

“The prevailing perception in the international media and scientific literature is that MPXV [mpox virus] is endemic in people in some African countries,” the group wrote at the time. “However, it is well established that nearly all MPXV outbreaks in Africa prior to the 2022 outbreak, have been the result of spillover from animals to humans and only rarely have there been reports of sustained human-to-human transmissions. In the context of the current global outbreak, continued reference to, and nomenclature of this virus being African is not only inaccurate but is also discriminatory and stigmatizing.”

When WHO renamed the virus to mpox, it had already renamed two variants of the virus. The former Congo Basin variant was renamed Clade one (I) and the West African variant is now Clade two (II). Clade is a scientific term for a group of organisms that have evolved from a common ancestor.

A brief history: Mpox was first discovered in 1958 in monkeys that were shipped from Singapore to Copenhagen, Denmark, for polio vaccine research. At the time, researchers called it a pox-like disease. Despite being named “monkeypox” in the following years, the source of the disease remains unknown, according to the CDC. African rodents and non-human primates like monkeys might harbor the virus and infect people. The first case of human mpox was found in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of Congo in a 9-month-old boy.

The 2022 outbreak: On July 23, 2022, nearly two months after the U.K. reported its first mpox case, the World Health Organization declared mpox a global health emergency — also called Public Health Emergency of International Concern or PHEIC — which signals the need of an international response to ramp up available testing, medications and vaccines.

The first mpox case in the U.S. was identified on May 18, 2022, in Massachusetts. On Aug. 4, 2022, the U.S. declared a public health emergency, which allows the administration to use federal funds to respond to the outbreak.

The virus: The mpox virus is a member of Orthopoxvirus genus, from the family Poxviridae, and is related to smallpox and cowpox viruses. Mpox is less contagious than smallpox and causes less severe illness. (Smallpox was declared eradicated worldwide in 1980. Chickenpox is from a different virus family called Herpesviridae.)

History of outbreaks in the U.S.: The first mpox outbreak outside of Africa was documented in the U.S. in 2003. Eighty-one cases in Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Ohio and Wisconsin were reported during the outbreak. The outbreak was linked to a shipment of animals from Ghana. In 2021, one instance of the infection was documented in a U.S. resident who had returned from Nigeria.

Transmission: Researchers still don’t know in which host the mpox virus naturally lives and reproduces, but several animal species are susceptible to the virus, including rope and tree squirrels, Gambian pouched rats, rodents named dormice and non-human primates (monkeys).

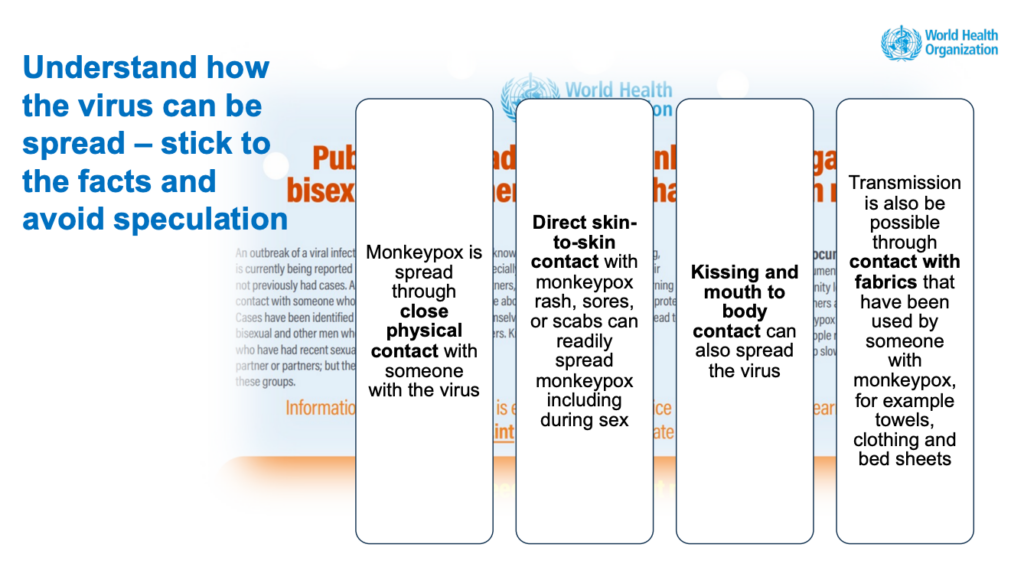

Animal-to-human transmission of the virus — also called zoonotic transmission — can occur from direct contact with the blood, bodily fluids or lesions of infected animals. Human-to-human transmission can result from close contact with respiratory secretions like droplets, skin lesions of an infected person or objects like bedsheets used by someone who has mpox. Transmission can also occur via the placenta from mother to fetus or during birth.

Transmission via respiratory droplets usually requires prolonged face-to-face contact. This puts health workers, household members and other close contacts of active cases at greater risk.

So far, data suggest that gay men, bisexual men and men who have sex with men make up the majority of mpox cases in the outbreaks in the U.S. and other countries. But anyone, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity, who has been in close, personal contact with someone who has mpox is at risk, according to the CDC.

Symptoms: The symptoms of the current mpox outbreak include a rash that could be on or near the genitals or anus. It can also be on the hands, feet, mouth, face and chest. Other symptoms are fever, chills, exhaustion, muscle aches, headaches and sore throat. The illness lasts between two to four weeks.

Death rate: Over the decades, the death rate from mpox infection has ranged from 0% to 11%, but researchers estimate the death rate from the current outbreak is about 0.03%.

Treatment: There is no specific treatment for mpox, but antivirals such as tecovirimat (TPOXX) may be recommended for people who are more likely to get severely ill, like patients with weak immune systems, according to the CDC.

Vaccines: Vaccination against smallpox has been shown to be 85% effective in preventing mpox. JYNNEOS, manufactured by Bavarian Nordic A/S, is currently the only FDA-licensed vaccine in the U.S. to prevent the infection. The vaccine was first approved in 2019 in the U.S. for the prevention of smallpox and mpox. People exposed to the virus can also get vaccinated. The CDC recommends vaccination within four days from the date of exposure. ACAM2000 is another vaccine that’s FDA-licensed to prevent smallpox, but it is associated with a higher risk of adverse reactions compared with JYNNEOS. For more on mpox vaccine availability, read the August 17 mpox outbreak alert by Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Health Security. This Vox piece by Keren Landman is also a good explainer about why ACAM2000 isn’t currently used. And Monkeypox Vaccine 101 by epidemiologist Katelyn Jetelina is a good overview.

A July 2022 report by the Kaiser Family Foundation explores at the local level whether jurisdictions are requesting the vaccines allocated to them. It finds that jurisdiction request rates for JYNNEOS vary widely. While most jurisdictions have requested their full supply of the vaccine, some have requested a percentage of their allocation. Ten states — Washington, Missouri, Kansas, Georgia, Nevada, Montana, South Dakota, Oklahoma, Kentucky, and Arkansas — had requested 50% or less of their share when the report was published.

Research roundup

Knowledge and Attitude Towards Mpox: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Darwin A. León-Figueroa, et al. PLOS ONE, August 2024.

The analysis of 27 studies with a total sample of 22,327 participants in 15 countries in Asia and Africa finds that overall, good knowledge about mpox and confidence in the ability to control the spread of the virus were low. The participants’ intention to get vaccinated against mpox was 58%, showing a relatively strong inclination towards using vaccination as a preventive measure. “Additional healthcare education and communication are crucial for improving

knowledge and attitudes regarding mpox,” the authors write.

High-Contact Object and Surface Contamination in a Household of Persons with Monkeypox Virus Infection — Utah, June 2022

Jack Pfeiffer; et al. CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, August 2022.

The report is based on testing the surfaces of the household of two mpox patients in May 2022. When Salt Lake County Health Department officials went to the home, the patients had already isolated themselves for 20 days. They told officials that they had cleaned and disinfected areas of their home where they spent a lot of time. The mpox virus DNA was found in many of the 30 samples collected, but there was no viable virus. This suggests “that virus viability might have decayed over time or through chemical or environmental inactivation,” the authors write.

“Monkeypox virus primarily spreads through close, personal, often skin-to-skin contact with the rash, scabs, lesions, body fluids, or respiratory secretions of a person with monkeypox; transmission via contaminated objects or surfaces (i.e., fomites) is also possible,” the authors write. “Persons living in or visiting the home of someone with monkeypox should follow appropriate precautions against indirect exposure and transmission by wearing a well-fitting mask, avoiding touching possibly contaminated surfaces, maintaining appropriate hand hygiene, avoiding sharing eating utensils, clothing, bedding, or towels, and following home disinfection recommendations.”

Epidemiologic and Clinical Characteristics of Monkeypox Cases — United States, May 17–July 22, 2022

David Philpott; et al. CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, August 2022.

The report describes the characteristics of 1,195 human mpox case reports in the U.S. between May 17, when the first U.S. case related to the 2022 outbreak was identified, and July 22. Of those, 99% were men and 94% reported male-to-male sexual or intimate contact during the three weeks before symptoms began. About 41% were white, 28% were Hispanic or Latino, 26% were Black and 5% were Asian. Genital rash, although reported in fewer than half of cases, was common; 36% of persons developed a rash in four or more body regions, the authors report. About 41% of patients were living with HIV.

“A substantial proportion of monkeypox cases have been reported among persons with HIV infection, and efforts are underway to characterize monkeypox clinical outcomes among these persons,” the authors write. “Clinicians and health officials implementing monkeypox education, testing, and prevention efforts should also incorporate recommended interventions for other conditions occurring among gay and bisexual men, including HIV infection, sexually transmitted infections, substance use, and viral hepatitis.”

Epidemiology of Early Monkeypox Virus Transmission in Sexual Networks of Gay and Bisexual Men, England, 2022

Amoolya Vusirikala; et al. CDC’s Emerging Infectious Diseases Journal, August 2022.

Published by researchers at the U.K. Health Security Agency in London, the study is based on phone interviews with 45 patients with mpox and was conducted between May 25 and 30, 2022. All but one person identified as gay or bisexual. About a quarter reported living with HIV and were receiving treatment. Sixty-four percent of patients reported attending sex-on-premises venues, such as bathhouses, festivals, private sex parties or cruising grounds, in the three weeks before developing symptoms. The authors define cruising as sexual activity with anonymous people in public spaces. However, 36% didn’t report any of those activities. Instead, they had had sexual activity with new partners or had met via dating apps.

“Our findings suggest that sustained domestic MPXV [monkeypox virus] transmission in sexual networks of GBMSM [gay, bisexual men, and men who have sex with men] in England has been occurring since at least April 2022, with potential importations and exportations from other countries in Europe,” the authors write. “To achieve outbreak control, targeted interventions for venues and their users are vital, including supporting enhanced cleaning of venues to prevent transmission via fomites, targeted health promotion to build awareness and inform risk management, and innovative approaches to support contact tracing of venue attendees.”

Two related studies: “Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Confirmed Human Monkeypox Virus Cases in Individuals Attending a Sexual Health Centre in London, UK: An Observational Analysis,” by Nicolò Girometti; et al., published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases in July 2022. And “Clinical features and novel presentations of human monkeypox in a central London centre during the 2022 outbreak: descriptive case series,” by Aatish Patel; et al., published in The BMJ in July 2022.

Tecovirimat and the Treatment of Monkeypox — Past, Present, and Future Considerations

Drs. Adam Sherwat, John Brooks, Debra Birnkrant and Peter Kim. NEJM, August 2022.

The perspective article discusses the nuances in the use of the antiviral drug tecovirimat (TPOXX), which has been approved for the treatment of smallpox under a regulation known as the “Animal Rule” and raises a conundrum: “How to manage compassionate access to a drug whose safety and efficacy in humans have not been established.”

Technical Report: Multi-National Monkeypox Outbreak, United States, 2022

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, July 2022.

The report provides an overview of mpox cases in the U.S. as of July 25, 2022, including 3,487 cases in 45 states, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico. The median patient age was 35. Of the 1,383 patients with information on sex assigned at birth, 99% were men. Of the 624 with information on sexual activity, 99% reported male-to-male sexual contact. Race and ethnicity data were missing for a large number of cases, but the available information showed that 38% were white, 32% were Hispanic and 26% were Black.

Many of the initial patients reported international travel in the 21 days before symptoms appeared, visiting countries where mpox was not endemic. Many reported participating in large festivals and other activities where close, personal, skin-to-skin contact likely occurred.

The technical report lists several priority research questions, including what medical interventions can be effective, how the virus is transmitted and how best to monitor mis- and disinformation and counter them.

Frequent Detection of Monkeypox Virus DNA in Saliva, Semen, and Other Clinical Samples from 12 Patients, Barcelona, Spain, May to June 2022

Aida Peiró-Mestres; et al. Eurosurveillance, July 2022.

Analysis of 147 clinical samples collected at different times from 12 patients revealed that the mpox virus was present in saliva from all cases. It was also frequently present in rectal swabs, nose swabs, semen, urine and feces.

“Our results contribute to an improved understanding of a likely complex transmission puzzle and underline other immediate areas for research such as the infectivity of bodily fluids, the frequency of secondary and asymptomatic cases or the impact of social and behavioral factors affecting viral transmission,” the authors write.

The Changing Epidemiology of Human Monkeypox — A Potential Threat? A Systematic Review

Eveline Bunge; et al. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, February 2022.

Published shortly before the current outbreak, this systematic review of existing literature was one of several papers sounding the alarm about the public health implications of the international community ignoring mpox.

“The waning population immunity associated with discontinuation of smallpox vaccination has established the landscape for the resurgence of monkeypox,” the authors write. “In light of the current environment for pandemic threats, the public health importance of monkeypox disease should not be underestimated. International support for increased surveillance and detection of monkeypox cases are essential tools for understanding the continuously changing epidemiology of this resurging disease.”

Human Monkeypox — After 40 Years, An Unintended Consequence of Smallpox Eradication

Karl Simpson; et al. Vaccine, July 2020.

The report notes that since the eradication of smallpox in 1980, about 70% of the world’s population is no longer protected against smallpox and that mpox, which is from the same family of viruses, is now a re-emerging disease.

“Monkeypox has been viewed as ‘just another neglected disease.’ Global travel and easy access to remote and potentially monkeypox-endemic regions are a cause for increasing global vigilance,” the authors write. “As monkeypox is no longer a rare disease, there is need for more rigorous epidemiological studies, with particular reference to zoonotic hosts, transmission potential and human case severity.”

Human Monkeypox: Epidemiologic and Clinical Characteristics, Diagnosis, and Prevention

Dr. Eskild Petersen; et al., Infectious Disease Clinics of North America, December 2019.

The study provides an overview of mpox and related outbreaks over the decades and stresses that mpox is “no longer ‘a rare viral zoonotic disease that occurs primarily in remote parts of Central and West Africa, near tropical rainforests.’”

A Systematic Review of the Epidemiology of Human Monkeypox Outbreaks and Implications for Outbreak Strategy

Ellen Beer and V. Bhargavi Rao. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, October 2019.

The report reviews 71 documents, including situation reports, investigations and case reports published between 1972 and 2018. The study provides a detailed analysis of available data.

The authors note that few studies based on virus samples were available. “Overall, samples are seldom taken, and very few cases are laboratory-confirmed,” they write. “Significant improvements in the quality and quantity of outbreak data collection are urgently needed to improve the monkeypox research portfolio to inform appropriate case management and public health response.”

The 2017 human monkeypox outbreak in Nigeria — Report of outbreak experience and response in the Niger Delta University Teaching Hospital, Bayelsa State, Nigeria

Dimie Ogoina; et al. PLOS One, April 2019.

The study investigates the 2017 mpox outbreak in Nigeria. While Nigeria reported three mpox cases between 1970 and 2017, it had a large outbreak with 228 suspected cases in 2017. Researchers reviewed the clinical characteristics of 21 cases at Niger Delta University Teaching Hospital, between September and December 2017. The median age was 29, ranging from 6 to 45 years. About 80% were male.

Most patients expressed fear and anxiety over facing stigma and discrimination from hospital staff, members of the community and family members, the authors write.

The most prominent challenge in hospital response was a delay in testing because none of the labs in Nigeria could test for the infection when the outbreak began.

“The Nigeria outbreak was characterized by predominant infection among young adult males and significant person-to-person secondary transmission,” the authors write. “These findings differ from previous reports … of human monkeypox where children below 10 years of age comprised 83% of the cases and secondary transmission was observed to be rare.”

The authors define secondary transmission as person-to-person transmission via respiratory droplets, direct contact with infected secretions of patients or from contact with contaminated patient environment, like bedding.

The authors also note that a substantial number of young adults had genital ulcers, which was less common in previously reported cases. “The role of genital secretions in transmission of human monkeypox, however, deserves further studies,” they write.

Extended Human-to-Human Transmission during a Monkeypox Outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Leisha Diane Nolen; et al. CDC’s Emerging Infectious Diseases Journal, June 2016.

The study reports a notable increase in mpox cases in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where the infection is endemic. The report includes 104 suspected cases between July and December 2013, compared with 13 cases in 2012 and 17 cases in 2011. In 50% of the cases, the virus was spread among the people in the household. The median age of patients was 10 with an age range between 4 months and 68 years. About 57% were male. There were 10 deaths. The infections were likely caused by exposure to wild animals or an infected individual.

“The high attack rate and transmission observed in this study reinforce the importance of surveillance and rapid identification of monkeypox cases,” the authors write. “Community education and training are needed to prevent transmission of MPXV infection during outbreaks.”

Additional research

The Threat of Mpox Has Returned but Public Knowledge About It Has Declined

Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania, August 2024.

The nationally representative survey of 1,500 U.S. adults, conducted in July 2024, finds that knowledge about mpox has declined, following an increase between July and August 2022, and so has the fear of the disease.

Health Care Personnel Exposures to Subsequently Laboratory-Confirmed Monkeypox Patients — Colorado, 2022

Kristen E. Marshall; et al. CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, September 2022.

The study finds that none of the 313 Colorado health care providers exposed to patients with mpox acquired the infection. Also, the use of recommended personal protective equipment and vaccination was low among the providers.

HIV and Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Persons with Monkeypox — Eight U.S. Jurisdictions, May 17–July 22, 2022

Kathryn G. Curran; et al. CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, September 2022.

The study finds that among 1,969 people with mpox in the U.S., 38% had HIV infection and 41% had a sexually transmitted infection in the prior year. Hospitalization was more common among those with HIV infection.

More recommended reading

- What You Need to Know About the History of Monkeypox, by Simar Bajaj, published in the Smithsonian Magazine in June 2022, delves into the history of mpox.

- What Scientists Know — and Don’t Know — About How Monkeypox Spreads, by Megan Molteni, published in STAT in August 2022, explains in detail what’s known and unknown about the routes of virus transmission. “What’s clear from the epidemiological evidence so far is that the current monkeypox epidemic is being driven overwhelmingly by the first of these [direct skin-to-skin contact] — in particular, close intimate contact between sexual partners,” she writes.

- Why the Monkeypox Outbreak is Mostly Affecting Men Who Have Sex with Men, by Kai Kupferschmidt, published in Science Magazine in June 2022, explains how interconnected sexual networks within the community of men who have sex with me may give the virus the ability to spread in ways that it can’t in the general population.

- He Discovered the Origin of the Monkeypox Outbreak — and Tried to Warn the World, by Michaeleen Doucleff for NPR, published in July 2022, tells the story of Dr. Dimie Ogoina, who diagnosed the first known case of the current international mpox outbreak in an 11 year-old-boy in 2017.

- How is Monkeypox Spread? is a good explainer published in August 2022 by epidemiologist Katelyn Jetelina in her Substack.

- Fighting Monkeypox, Sexual Health Clinics Are Underfunded and Ill-Equipped, by Liz Szabo and Lauren Weber for Kaiser Health News, published in July 2022, notes, “Sexual health clinics have been stretched so thin that many lack the staff to perform such basic duties as contacting and treating the partners of infected patients.”

- New Data From Several States Show Racial Disparities in Monkeypox Infections, by Usha Lee McFarling, Katherine Gilyard and Akila Muthukumar, published in STAT in August 2022, highlights extreme racial disparities in mpox cases in some states, compounded by lack of access to the vaccine.

- What Does It Mean to Declare Monkeypox a PHEIC? by Talha Burki, published in Lancet Infectious Diseases in August 2020, explains what a public health emergency declaration by WHO does and doesn’t do. In another article, Monkeypox as a PHEIC: Implications for Global Health Governance, published in August 2022 in The Lancet, Clare Wenham and Mark Eccleston-Turner also explore the implications of the declaration.

Resources for journalists

- Several journals, including JAMA, The Lancet journals, Nature journals, BMC journals and Annals of Internal Medicine have been providing free public access to their mpox content.

- You can find WHO’s main page for monkeypox here and the CDC’s here. And here’s CDC’s guidance for schools. Here’s CDC’s mpox case and trend data.

- WHO has weekly reports on emergency situations updates for mpox.

- CDC’s “2022 Monkeypox Outbreak Global Map” keeps track of confirmed cases and deaths. WHO also keeps track of reported cases on its Health Emergency Dashboard. Our World in Data is another source for numbers and reports 7-day averages and weekly trends.

- Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Health Security has a weekly outbreak alert for mpox and provides a comprehensive overview of the latest developments and research in the U.S. and around the world.

- Special Advisory: Covering Monkeypox by the Association of LGTBQ Journalists provides guidance to journalists and newsrooms on the language they use when covering mpox. How to Talk About Monkeypox Effectively, Without Stigmatizing Gay Men, published on NPR’s All Things Considered in August 2022, is also a good guide. And CNN’s Sara Ashley O’Brien has sage advice about choosing images for your mpox stories.

- Reducing Stigma in Monkeypox Communication and Community Engagement, a document by the CDC, discusses how the agency is framing communication around mpox to avoid marginalizing stigmatizing groups that may be at increased risk of the infection.

- How to Cover Health Inequities in U.S. Monkeypox Data Trends, by Margarita Birnbaum and Bara Vaida, published on the Association of Health Care Journalists’ blog Covering Health in August 2022, is a tip sheet to help journalists shed light on the disparities in mpox infections. This August 2022 report by the Kaiser Family Foundation has data on mpox vaccinations in the U.S. by race and ethnicity.

- FDA Monkeypox Response explains the role of the FDA in the current public health emergency.

- If you’re curious about mpox strains, check Nextstrain, an open-source project that provides a view of publicly-available data along with visualizations for use by anyone.

- In Monkeypox Experts to Follow on Social Media, also published on the Covering Health blog, Bara Vaida shares her Twitter list of mpox experts.

Free multimedia collections for news stories

- The CDC has these graphics, images and videos about mpox. It also has b-roll of the agency’s buildings.

- WHO has a large collection of photos, including people getting vaccinated and patients with mpox.

- This WHO graphic on recovering from mpox at home shows what steps individuals should take.

- SciLine, a free service for journalists based at the American Association for Advancement of Science, has several video clips of expert interviews, which you can embed in your stories.

Expert Commentary