Much of the academic research and media coverage of mass shootings focuses on the people who were killed. Less attention is focused on people who were injured and survived these tragedies. In most cases nonfatal mass shooting injuries outnumber deaths and a portion of the survivors face long-term physical and mental health consequences, according to a study published in May in the Western Journal of Emergency Medicine.

“Nonfatal Injuries Sustained in Mass Shootings in the US, 2012-2019: Injury Diagnosis Matrix, Incident Context, and Public Health Considerations,” includes 13 mass shootings between 2012 and 2019. It is a more in-depth analysis of the data first reported by the authors last year in JAMA Network Open.

“I had the idea to bring another level of understanding about mass shootings and how horrible they are,” says Dr. Mark Langdorf, the study’s senior author and a professor of clinical emergency medicine at University of California, Irvine. “The point we make is that [mass shootings have] a huge impact on the patient, on health care resources, on public health. … The families of the survivors have their whole lives changed.”

Among the study’s surprising findings: 37% of the mass shooting injuries didn’t involve bullet wounds; people were trampled, fell off a fence, had a stroke or heart attack, or had anxiety or other mental health-related symptoms.

Research on mass shooting injuries is limited, in part because there’s no national database for them and their short- and long-term outcomes. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Violent Death Reporting System tracks firearm deaths but not injuries.

For their study, the authors gathered and analyzed data with the help of local emergency physicians and trauma surgeons at hospitals treating those mass shooting injuries. But not all hospital were willing to collaborate or had research capabilities. In some cases, data for patients who didn’t have serious injuries were incomplete.

To overcome these barriers in the future, the authors call for a national registry to track nonfatal mass shooting injuries.

“Longitudinally, the care we provide for these patients goes on for years,” Langdorf says. “We should therefore have a national accounting and reckoning of injuries from mass shootings and record required hospital report.”

Langdorf described the case of one patient who was treated at his hospital after getting injured during the 2017 the Route 91 Harvest music festival mass shooting in Las Vegas.

“We were able to follow their medical records for two and a half years. [The person] had five surgeries. They ran up [$450,000] in bills. … Two and a half years later, they were not back to work, they were still on disability,” he says.

The study and its findings

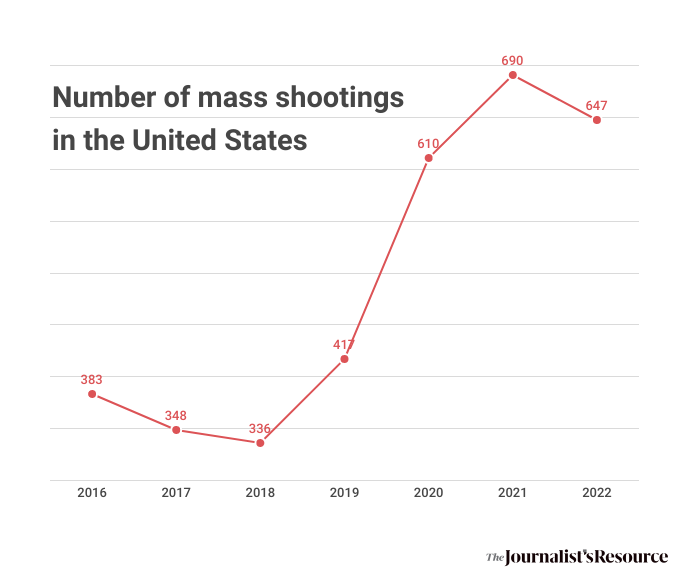

The Gun Violence Archive, a nonprofit organization that collects information from more than 7,500 law enforcement, media, government and commercial sources daily, defines a mass shooting as an event where four or more people are shot or killed, excluding the shooter.

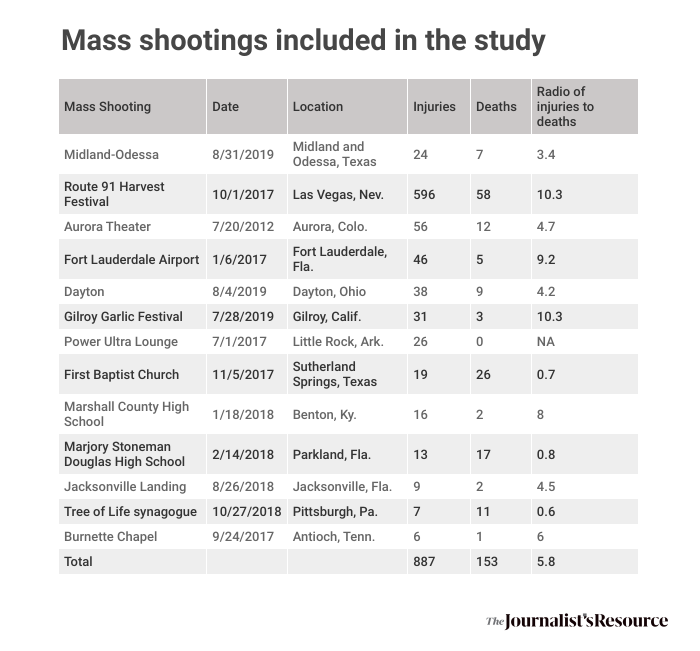

For the purpose of the their study, the authors focused on mass shootings that involved 10 or more nonfatal injuries occurring between 2012 and 2019. Of the 21 mass shootings that fit the criteria, they were able to collect data on 13.

Researchers couldn’t collect data from the other eight mass shootings, including the 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, Fla., and the 2019 Walmart shooting in El Paso, Texas. There were several reasons, including lack of hospital research infrastructure, lack of staff because of the COVID-19 pandemic, refusal of some health systems to allow physicians to participate in the project for public relations reasons and the age of some medical records, the authors write. In some cases, they couldn’t find a collaborator at the hospitals.

The 13 mass shootings resulted in 153 deaths and 887 injuries. Researchers were able to gather data on 403 of the injured patients.

Below is a summary of their findings, in three groups: The characteristics of the mass shootings, the physical injuries and the psychiatric conditions.

1. The mass shootings

The analysis shows semiautomatic firearms were used in all of the 13 mass shootings. In total, the shootings involved 50 weapons. Semiautomatic guns automatically load cartridges and fire one bullet each time the trigger is pulled. In 23% of the cases the shootings were associated with hate crimes.

Also:

- The majority of the patients were white (69.9%), followed by Hispanic (15.3%), Black (11.4%) and Asian (3.4%).

- The median age of injured patients was 33, and 52% were women.

- Three of the mass shootings occurred at religious sites, three at bars or nightclubs, two at schools, and two at concerts or festivals.

- The 13 mass shootings involved 30 semi-automatic assault rifles, 13 semi-automatic pistols, three shotguns, three handguns, and one bolt-action (non-automatic) rifle.

- Most legally obtained firearms were purchased from a federally-licensed dealer, including all 24 firearms used in the Las Vegas mass shooting.

- More than 90% of the shootings occurred within one mile of schools or parks.

2. The physical injuries

Several studies have investigated injuries sustained from gun violence, but Langdorf points out a distinct difference between injuries from mass shootings and those from neighborhood gun violence.

“The majority of mass shootings involve [semi-automatic] rifles, and those injuries are orders of magnitude worse from a perspective of how much energy is delivered to the victim,” he says.

“These are horrific injuries,” he adds. “People might be functional on the surface a year later, but some of them are still being tended to for their original injuries.”

Among the study’s findings:

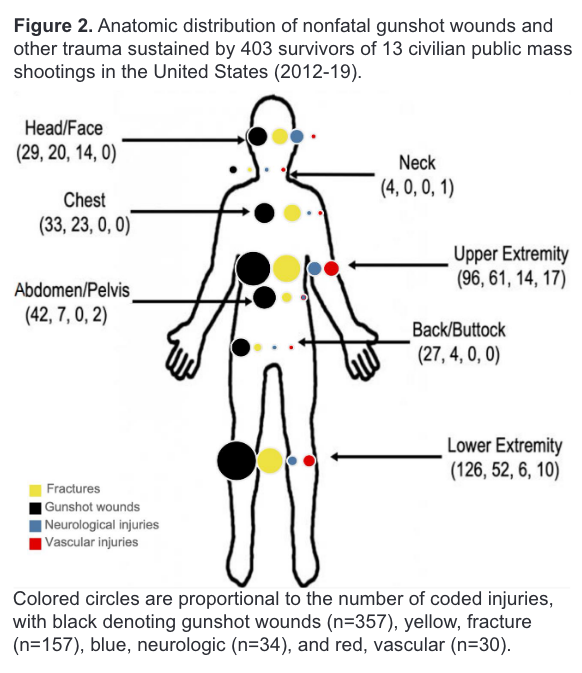

- Of the 403 patients, 252 had gunshot wounds (62.5%), 112 had other physical injuries not involving bullets (27.8%), and 39 patients (9.7%) had no physical injuries.

- 64% of the patients had either no insurance or public insurance (Medicare or Medicaid), a rate that’s similar for all firearm injuries, the authors note.

- The average hospital cost per patient was $31,885.

- Of the 39 patients who had no physical injuries, 21 had a psychiatric diagnosis. Others had symptoms such as hearing loss or worsening of existing medical conditions.

- The most common injuries that didn’t involve a gunshot were from falling, stampedes, trampling, blunt force trauma and heart attacks.

- A little over half (53.1%) were taken to the hospital by ambulance. Others arrived by cars or walked in.

- For all patients, the most frequent injured body part involved chest, followed by abdomen and shoulder or upper arm.

- 36.5% of the 403 injured people were admitted to the hospital. The median length of hospital stay was 4 days.

- Of the 143 admitted to the hospital, 11.2% were readmitted or had outpatient procedures within 30 days at the same hospital. Within one year, 46.2% of the patients were readmitted to the same hospital.

- Among 364 patients with physical injuries, 44% had a physical disability at discharge and 13.3% were sent to long-term care.

- Some injured patients also had non-traumatic diagnoses, including worsening of asthma, hearing loss or heart attack.

3. The mental health impact

In total, 50 patients had one or more psychiatric diagnoses, including anxiety or panic, acute stress disorder, major depressive disorder or symptoms, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

In addition:

- Among those who survived the mass shooting, 12% had acute mental health issues, although the authors speculate that the number is higher, since many patients were discharged from the emergency department before detailed evaluation of their emotional state.

- Fifteen patients were formally diagnosed with acute stress disorder, and six were diagnosed with PTSD by the time of hospital discharge. These 21 patients formed 28% of all psychiatric diagnoses. Symptoms of acute stress disorder last between three to 30 days, while PTSD symptoms last more than 30 days. It is possible that some of the patients with acute stress disorder may have subsequently developed PTSD, the authors note.

Recommendations

The authors’ main recommendation is a national registry for people who are injured in mass shootings.

The CDC established the National Violent Death Reporting System in 2002, to which all 50 states and the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico report. The system tracks all types of firearm deaths, including intentional and unintentional. However, it does not track nonfatal firearm injuries.

The authors couldn’t include data from 300 Las Vegas mass shooting patients because the hospitals didn’t give them approval to access their records.

“That underscored the need for a registry where hospitals should report” these injuries, Langdorf says.

The authors also recommend community mental health resources such as critical incident stress debriefing, which is a facilitator-led gathering conducted soon after a traumatic event with individuals considered to be under stress from trauma exposure, and psychological interventions, such as Psychological First Aid, which is designed to promote safety and stabilize the survivors of disasters.

They also recommend future research and public policy change to focus on “assessment of the potential impact of ‘smart guns,’ which can only be fired by the registered user; increased background checks and waiting periods (including closing so-called ‘gun-show loopholes’ that avoid background checks); appropriate application of concealed weapon permits; removal of tort liability protections for gun manufacturers; restriction of semi-automatic and automatic weapons; and restriction of large-capacity magazines, which is specifically important to mitigate the harm from [mass shootings].”

“[People] get shot and have a horrific life afterwards, where they can’t work and they get post-traumatic stress disorder and physical disability that affects them the rest of their life,” says Langdorf. “And that’s all silent in the media. And that’s why we did this paper because it’s not a silent injury. It’s a horrible injury.”

Additional research on mass shooting injuries

In “The Bullets He Carried,” published in The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine in 2020, Dr. Stephen Hargarten reports on his research comparing the energy released from a modern, high-speed rifle bullet with that of musket ball similar to those used in the 1780s.

“We found that the rifle bullet’s energy release was over nine times greater than the musket ball because of the rifle bullet’s significantly greater velocity compared to the musket ball’s velocity,” Hargarten writes.

One study, “Injury characteristics of the Pulse Nightclub shooting: Lessons for mass casualty incident preparation,” published in 2020 in the Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, provides a detailed analysis of injuries, both fatal and nonfatal, and the hospital resources needed to respond to a mass casualty event. “Survivors commonly sustain multiple, life-threatening ballistic injuries requiring emergent surgery and extensive hospital resources,” the authors write.

Another study, “Characteristics of survivors of civilian public mass shootings: An Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma multicenter study,” published in 2021 in the Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, includes data on 31 mass shooting events between 1999 and 2017, involving 191 survivors treated at trauma centers. Authors conclude survival after mass shootings “appears to be related to an absence of severe injury and need for immediate medical or surgical intervention.”

In “Wound patterns in survivors of modern firearm related civilian Mass Casualty Incidents,” published in 2019 in American Journal of Disaster Medicine, a study based on data from 19 survivors of two mass shootings taken to a level 1 trauma center in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, the authors describe the nature of 29 bullet wounds. They call for efforts that teach the public how to stop bleeding with efforts such as the Stop the Bleed campaign, which is run by the American College of Surgeons’ Committee on Trauma.

Additional research on mental health impact of surviving firearm injuries

Several studies have addressed the mental health impact of surviving firearm injuries, although not all are specifically about mass shootings.

In “Mental Health and Health-Related Quality of Life After Firearm Injury: A Preliminary Descriptive Study,” published in the Annals of Internal Medicine in May, and based on 87 adults who were admitted to a level 1 trauma center in a midwestern U.S. city, survivors reported PTSD after an injury that continued to affect them at 6 months. The authors highlight the need to better understand and manage mental health consequences of firearm injuries.

In “Psychological Impacts of Retained Bullets From the Perspective of Survivors,” published in The American Surgeon in May, researchers interview 24 firearm injury survivors in Atlanta who still had a bullet lodged in their body. The find survivors “experience a range of psychological impacts that are far-reaching and affect daily activities, mobility, pain and emotional wellbeing.”

“Healthcare utilization after mass trauma: a register-based study of consultations with primary care and mental health services in survivors of terrorism,” published in BMC Psychiatry in 2022, looks at registry data on primary care and mental health consultations of 255 people who were injured of the 2011 Utøya youth camp attack in Norway, find few of the survivors used mental health services before the attack, while most did after the attack.

In another study, “The impact of a terrorist attack: Survivors’ health, functioning and need for support following the 2019 Utrecht tram shooting 6 and 18 months post-attack,” published in Frontiers in Psychology in 2022, authors interviewed 21 survivors of the shootings in Utrecht, Netherlands. The authors find that even though 6 months after the attack most of the survivors had resumed their daily activities like work or school, more than half had psychological and physical symptoms, including PTSD and fatigue.

“Mental health outcomes from direct and indirect exposure to firearm violence: A cohort study of nonfatal shooting survivors and family members,” published in the Journal of Criminal Justice in 2022, analyzes Medicaid claims data between 2007 and 2016 for 2,838 children who survived a shooting. It finds the prevalence of mental health issues for family members increased by 3% in the year after the shooting.

“Long-term Functional, Psychological, Emotional, and Social Outcomes in Survivors of Firearm Injuries,” published in JAMA Surgery in 2019, finds that the 183 young adults who survived gunshot wounds reported worse physical and mental health compared with the general population. Nearly 49% had probably PTSD. Their unemployment increased by 14% and substance use by 13% after injury.

Additional reading

“‘It will stay with me forever: The experiences of physicians treating victims of public mass shootings.” Rebecca Cowan, et al. Traumatology, June 2023.

“The cost of surviving gun violence: Who pays?” Patrick Boyle. AAMCNews, October 2022.

“Changes in Health Care Spending, Use, and Clinical Outcomes After Nonfatal Firearm Injuries Among Survivors and Family Members.” Zirui Song, et al. Annals of Internal Medicine, June 2022.

“In 2019, Congress Pledged Millions to Study Gun Violence. The Results Are Nearly Here.” Chip Brownlee. The Trace, June 2022.

“Towards a National Definition and Database for Nonfatal Shooting Incidents.” Natalie Kroovand Hipple. Journal of Urban Health, April 2022.

“Increases in Actual Health Care Costs and Claims After Firearm Injury.” Megan Ranney, et al. Annals of Internal Medicine, December 2020.

“Long-term Functional, Psychological, Emotional, and Social Outcomes in Survivors of Firearm Injuries.” Michael Vella, et al. JAMA Surgery, November 2019.

“The Mental Health Consequences of Mass Shootings.” Sarah Lowe and Sandro Galea. Trauma Violence Abuse, January 2017.

“Post-Discharge Needs of Victims of Gun Violence in Chicago: A Qualitative Study.” Desmond Patton, et al. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, September 2016.

Firearm research funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Expert Commentary