The story opens with a YouTube video, a few weak punches thrown among elementary school kids and a twisted mix of tragedy and conflicted consciences, recounted in gripping detail based on 38 hours of audio recordings the reporters obtained.

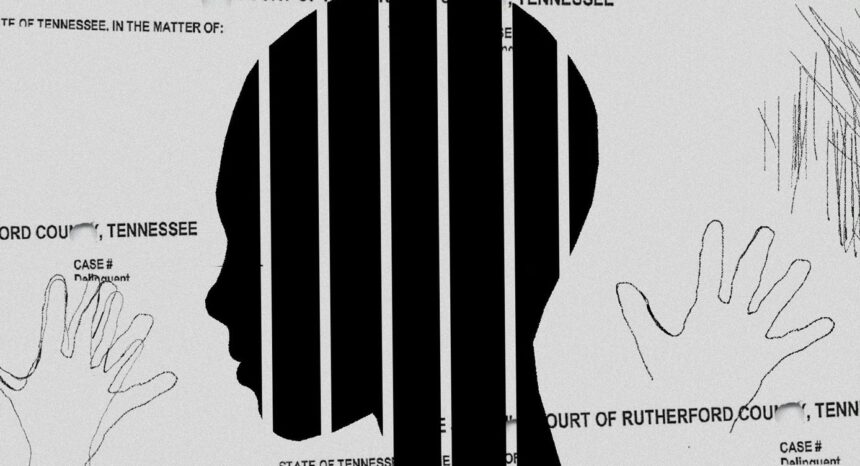

During March 2016, a scuffle took place off-campus involving students at Hobgood Elementary School in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. One kid, a bystander, held up a cellphone and recorded a 5- and a 6-year-old “throwing feeble punches at a larger boy as he walked away, while other kids tagged along, some yelling,” write Meribah Knight, a senior reporter at Nashville Public Radio, and Ken Armstrong, a reporter with ProPublica, in their October 2021 story, which describes years of misconduct and stark racial disparities in the Rutherford County juvenile justice system.

Weeks later, on April 15, three police officers “crowded into the assistant principal’s office at [Hobgood] and Tammy Garrett, the school’s principal, had no idea what to do,” Knight and Armstrong write. “One officer, wearing a tactical vest, was telling her: Go get the kids. A second officer was telling her: Don’t go get the kids. The third officer wasn’t saying anything.”

The police were there because of the video. Not for the kids caught fighting, but to arrest “the children who looked on,” on allegations of “criminal responsibility for conduct of another,” a crime that is not even on the books. Knight and Armstrong write:

“It’s not an actual charge. There is no such crime. It is rather a basis upon which someone can be accused of a crime. For example, a person who caused someone else to commit robbery would be charged with robbery, not ‘criminal responsibility.’”

Some of the children at Hobgood were handcuffed. In all, 11 children were arrested for being bystanders, four at school, others at their homes. Ten of those children — six boys and four girls, all of whom are Black — were eventually charged. Four of the boys were jailed for a combined total of six days.

Read the story — “Black Children Were Jailed for a Crime That Doesn’t Exist. Almost Nothing Happened to the Adults in Charge” — for the full narrative, including lines such as this from the day of the Hobgood arrests: “On this sunny Friday afternoon in spring, she wore her hair in pigtails.” The pigtailed girl was 8 years old, and was handcuffed. Once police brought her to the Rutherford County Juvenile Detention Center, officers realized they had no petition for her. She went home that day with her mother.

Donna Scott Davenport has run the county’s juvenile justice system for two decades. In January, she announced she would not seek reelection as juvenile court judge amid pressure from state lawmakers after the joint investigation and other media coverage.

In holding that position since 2000, Davenport has wielded enormous power in Rutherford County, “appointing magistrates, setting rules and presiding over cases that include everything from children accused of breaking the law to parents accused of neglecting their children,” write Knight and Armstrong.

In a follow-up article published Dec. 30, 2021, the reporters obtained data showing that from July 2010 to June 2021 minors in Rutherford County were jailed at least 6,350 times. The kids booked were Black in 38% of those cases, roughly double the percentage of Black kids in the county. The data show “that the county is an outlier compared to what’s been happening in recent years regarding racial disparities in juvenile justice,” Knight and Armstrong write. “In most of the country, the racial disparity has been decreasing. Rutherford County, meanwhile, has gone the opposite direction.”

Story origins

The arrests at Hobgood made headlines locally and nationally. Knight, who had moved from Chicago to Nashville just weeks before the arrests, knew the initial news coverage wasn’t telling the whole story.

As she and Armstrong write, “left unknown was all that led up to the arrests; what the children, police and school officials, experienced, in their voices; and what the case revealed about the county’s failed juvenile justice system as a whole.”

By 2017, Knight was reporting for Nashville Public Radio. She went to the families’ lawyers and told them she was going to cover the case. “They wanted someone in the media to understand,” Knight says. Listeners heard her first story on the case in May 2017 on WPLN, Nashville’s National Public Radio affiliate.

After that radio spot, lawyers provided Knight with reams of documents and she started searching PACER, the federally run online repository of court records. “I was just like, there’s so much here, this is crazy,” Knight says. While reporting other stories, she kept trying to understand the Hobgood arrests — and the story of the larger issues within the Rutherford County juvenile justice system.

In October 2020, she joined ProPublica through its Local Reporting Network. Armstrong teamed with Knight several months later. The Local Reporting Network program began in 2018 to support investigative journalism in cities with populations of less than 1 million. ProPublica reimburses newsrooms for the selected reporters’ salaries and provides guidance and expertise from veteran reporters on the ProPublica staff. Stories produced through the network are co-published by ProPublica and their partner newsrooms.

“We all knew that it was a special story and it was clear that Meribah had done so much work on it already and had such an ambitious plan,” Armstrong says.

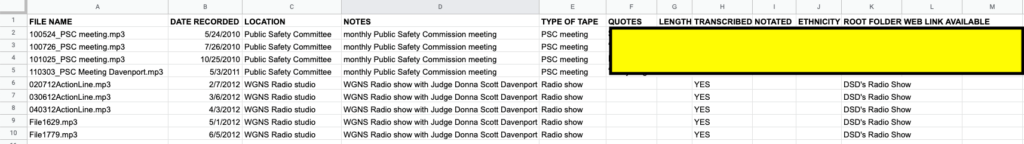

Their skills were complementary, with Armstrong’s background writing for print and online and Knight’s experience in radio. They knew off the bat, given the volume of recordings they had to sift through, that they wanted the written story to include audio components. In addition to nearly a workweek’s worth of deposition video to parse, Knight and Armstrong watched video recordings of 137 Rutherford County Public Safety Committee meetings from 2009 to 2021.

They also listened to or transcribed more than 60 hours of local radio interviews with Davenport. For a decade, she had been a regular guest on WGNS, based in Murfreesboro, where she presented a tough-talking, tough-love persona. She had called herself the “mother of the county,” Knight and Armstrong report. On the radio, she once described her judicial philosophy regarding local children like this: “Being detained in our facility is not a picnic at all. It’s not supposed to be. It’s a consequence for an action.”

In the story, readers can click that line and hear Davenport say those words.

“People respond differently to hearing things as opposed to reading them,” Armstrong says. “We thought having a little bit of the audio in there will allow people to have a snippet. It was also just a very brief preview of what’s to come.”

Knight and Armstrong are now working on a podcast based on their reporting on the Hobgood arrests and juvenile justice in Rutherford County. It’s due out later this year.

‘The biggest step to power is the first step’

Davenport’s ascent began in 1998 when she became a juvenile court referee, “akin to a judge,” Knight and Armstrong write. She had been an attorney for three years, nine years after graduating from law school and after failing the bar exam four times. The reporters asked the county judge who appointed her why he chose Davenport for that role. He said, “I really can’t go back and tell you.”

It’s a “very pregnant, pithy line,” Knight says. Armstrong adds, “That’s how she came to first sit on the bench, and, as reporters know, the biggest step to power is the first step. Once you’re elected or once you’re on the bench, once you’re in the position of an incumbent, the odds of you being removed are diminished — especially as time passes.”

What the Hobgood students experienced that spring day was not uncommon for juveniles in Rutherford County whose paths crossed with police. Davenport in a 2003 memo instituted the process: “arrest, transport to the detention center for screening, then file charging papers,” Knight and Armstrong write. And since 2007, even truancy and other alleged minor violations could land a kid in jail. But in the rest of Tennessee, police “typically avoid cuffs and custody, particularly in less serious cases,” Knight and Armstrong explain in their article.

Charges against the Hobgood children were dropped in June 2016 after public outcry following the arrests. A class-action lawsuit took shape in 2017 that sought monetary settlements for hundreds of juveniles detained or arrested over the years in Rutherford County. All 11 children arrested at Hobgood received a combined $397,500 in settlements, Knight and Armstrong report. In May 2017, a federal judge ordered the county to stop arresting and imprisoning kids on minor charges. In June 2021, Rutherford County agreed to pay up to $11 million to settle the class action lawsuit. Though Davenport has said she won’t seek reelection, she will remain on the bench until her term ends in August, despite widespread calls for her resignation.

Knight and Armstrong’s initial story struck a raw nerve with readers and listeners. It was viewed more than 2 million times and one Twitter thread from Armstrong has so far received more than 65,000 retweets and nearly 140,000 likes. Knight has discussed the story on national radio and television, including on “All Things Considered,” “The Takeaway,” “Here & Now,” “PBS Newshour” and the BBC World Service Radio.

Keep reading for seven tips from Knight and Armstrong on filing open records requests, keeping timelines and staying organized, and using software to help make sense of large audio and video files.

Tip 1: Remember when you receive public records, go for the underlying records too.

Knight filed nearly five dozen records requests to obtain documents and audiotaped interviews. (Under Tennessee law, only state residents can file open records requests; Armstrong is not based there.) She ended up getting almost all the items requested.

Knight recalls how a single page in a 140-page report based on an internal police investigation related to the Hobgood arrests helped move her reporting in a new direction. That one page explains that the report was “based on audio interviews with this list of 20 people. And we’re like, ‘We’ve got to get those audio interviews,’” she says.

Pay attention to the records you receive, Armstrong says. They can often hint at other records you should ask for, which may include audio and video files.

“Always go for the underlying records,” he says. “Every time you read a record, see if it is referring to, or has arrows pointing to, additional records.”

Though the Tennessee government stopped producing its annual report on county juvenile lockup numbers after 2014, it still had to collect the data by law. Knight and Armstrong knew they had to request that data for subsequent years.

“The absence of [public] data is such a big part of this story,” Knight says. “There was just this huge gaping hole in multiple ways. Some of it felt like laziness and then other times it felt like evasiveness. But it became much more of a bigger part of the story of accountability.”

Tip 2: Find out if records request fees can be waived.

The records Knight and Armstrong obtained were relatively expensive, with fees reaching into the thousands of dollars, Knight recalls. The costs were understandable — government employees had to go through dozens of hours of audio and video recordings to redact names of minors. In this case, there was no question in the reporters’ minds that their news organizations would cover the fees. Freelance journalists or those working for newsrooms with tighter budgets may not be able to afford such costs. Still, not all is lost.

Most states allow those working in the public interest, such as in service of news gathering and dissemination, to request that fees be waived.

“I don’t think we take advantage of that enough,” Armstrong says. “That should always be part of the [records request] letter if you’re working in a state that has that clause.”

He adds, “A lot of times fees are discretionary, but we treat them as being required. When they’re discretionary we should seize upon that and ask that fees be waived. That’s not only helping us, that’s helping other journalists out there — if you get these public agencies accustomed to the idea of, yes, there are times when not only we can provide these for free but we should provide them for free.”

For journalists who hit an insurmountable brick wall of fees, ask to inspect records. Knight has spent hours sitting at police department computers inspecting records. Sometimes, an agency is not trying to be obtuse, but rather doesn’t have the time or budget to pay for their staff to make photocopies, Knight explains.

“I’ve done that a lot, particularly with federal agencies,” Armstrong says. “A lot of times, like federal archives, they’ll let you just go in there, they’ll bring out the boxes. You have your phone and you’re just going page by page by page scanning it into your phone. It’s time consuming, right? So there is a cost on that end. But you’re not paying any fees for the records.”

Tip 3: Take care not to re-traumatize sources, especially when reporting on minors.

If people who have experienced trauma say no to an interview, honor that, Knight says. They may not be ready to share their story.

Also, consider not using full names. For the kids arrested at Hobgood who were still minors, Knight and Armstrong didn’t ask to use their full names. For the kids now over 18, Knight and Armstrong gave them the option of using their full names or only being identified by their initials.

“I was just being really sensitive, and sometimes overly sensitive,” Knight says. “Like when they said, ‘Yeah, you can use my name,’ I’m like, ‘OK, are you sure?’”

After the story made the rounds on social media, Knight went back to her main sources to check in. For example, she wrote to Garrett, the Hobgood principal, who reported to Knight that she had received only positive comments related to the coverage.

“It was really nice to know that the relationships we had spent so much time cultivating, that that trust was still there, even after this went viral and went far out of our control,” Knight says. “The way I report, I’m very much of a relationship-first reporter. I work really hard on building those relationships.”

Knight and Armstrong also suggest that reporters interviewing and producing stories about minors actively try to remember what life was like when they were young. Doing that helped inform “all my questions,” Knight says. “You’re just in such a different mindset when you’re a kid, you’re thinking about totally different things.”

Tip 4: Establish basic facts and keep a timeline of events.

“This story is like a Russian novel,” Knight says, referring to the sheer number of documents obtained, characters, twists and turns. Because she and Armstrong are reporting on a juvenile court system, basic identifying information that would have been public in the adult court system is withheld. To be able to definitively say the number of kids arrested, the age of the youngest arrested and other crucial details required numerous calls to attorneys, families and cross checking with clues from court records.

“That was a big lift but once it was done, I think there was a sense of relief,” Armstrong says. “We felt like, now we can write with authority.”

Timelines are essential when covering a complex story. Armstrong used Microsoft Word to create one. Knight then linked from the timeline to reporting memos she’d written and saved in Google Drive. It wasn’t fancy, and it didn’t need to be. It served its purpose as a quick reference for the facts the reporters had firmly established.

“A timeline is incredibly helpful when you have a sequence of events that, in our case, extended beyond 20 years,” Armstrong says.

Tip 5: Use software tools to sift through hours of video and audio.

Knight used a transcription program called Trint, which she has been using for years, to organize the extensive audio files, such as Davenport’s years of radio interviews. The transcriptions weren’t perfect, but it’s much faster to read transcripts than listen to audio, Armstrong says. Every line within Trint links to the related audio, which Knight says is useful for getting exact wording for quotes.

“I also keep a master tape log, which is really amazingly helpful,” Knight says. “It’s great because I keyword things and then when you’re dealing with hundreds of hours of audio — which is what we’re dealing with now doing the podcast — you have to be able to search and find things really quickly.”

Because Davenport declined to be interviewed, the reporters relied on the radio spots and court depositions to understand her character and judicial views. Armstrong points out that each provided a counter-balance — the radio interviews were largely friendly, allowing Davenport to develop her public persona as she saw fit, whereas the depositions resulting from the lawsuits were more combative and probing.

Tip 6: Weave data into narratives and use signposts to highlight crucial numbers when reporting for radio or podcasts.

There are numerous ways to present data in a visually compellingly way online, in print or on TV. But presenting data for a radio spot or podcast requires a different way of thinking. Knight says audio formats are inherently and intensely character driven, so data are often presented within the course of telling a person’s narrative.

Another way to present data within audio is to use what radio reporters call signposting. It’s a technique in which a host clearly and blatantly tells listeners what’s happening. It can be used for a transition between topics: “OK, we’ve dealt with that part of the story, and now we’re moving on to something a little bit different,” writes former NPR correspondent Chris Joyce. Signposting can also be useful for conveying data.

“A lot of times in radio we’re just going to be like, ‘Listen, if there’s one number that you remember just remember this 48%, because it keeps coming back,’” Knight says, referring to the 2014 juvenile lock-up rate in Rutherford County. “You do kind of have to be, in blinking lights, [pointing out] this is the number that’s going to come back again and again. Do not forget it.”

Tip 7: Take care and take time out when covering traumatic events.

Knight says it helps to take breaks, whether that means reading fiction, exercising, or doing something else that’s mentally healthy and away from a difficult reporting task.

Armstrong says it’s always a good idea for journalists who are feeling overwhelmed to contact the Dart Center for Journalism & Trauma at Columbia University. “I don’t think we should be shy about reaching out to them,” he says. Armstrong, one of the reporters who wrote the Pulitzer Prize-winning article “An Unbelievable Story of Rape,” also put together this tipsheet for journalists coping with stress, based on insights from journalists who have spent years reporting on traumatic incidents.

Read the stories

- Black Children Were Jailed for a Crime That Doesn’t Exist. Almost Nothing Happened to the Adults in Charge.

- Outrage Grows Over Jailing of Children as Tennessee University Cuts Ties With Judge Involved

- Tennessee Children Were Illegally Jailed. Now Members of Congress Are Asking For an Investigation.

- New Documents Prove Tennessee County Disproportionately Jails Black Children, and It’s Getting Worse

Expert Commentary