On Sept. 28, the White House is hosted a conference on hunger, nutrition and health — the second conference of its kind in five decades — and introduced a 40-page national strategy as a roadmap toward the goal of ending hunger and increasing healthy eating by 2030.

Among the drivers of the national strategy are food insecurity, which affects millions of Americans, and the increasing rates of diet-related diseases like obesity and diabetes.

The national strategy is built on five pillars: improving access to affordable food; prioritizing the role of nutrition and food security in overall health; empowering consumers to make healthy food choices; making it easier for people to be more physically active; and enhancing food and nutrition research.

“Lack of access to healthy, safe, and affordable food, and to safe outdoor spaces, contributes to hunger, diet-related diseases, and health disparities,” according to the conference’s website. “The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these challenges further.”

It’s been more than 50 years since the White House has held such a conference.

The first and only White House Conference on Food, Nutrition, and Health was held in 1969 during the Nixon administration and it led to the launch of programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program — or SNAP — the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children — known as WIC — and changes to food labels.

When the first conference was held, one of the main concerns was that families and children were not getting enough calories. In the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s conditions like rickets and night blindness were common as a result of vitamin deficiencies, explained Dr. Dariush Mozaffarian, a renowned expert on food systems and cardiologist, in a Sept. 22 video conversation about the White House conference, hosted by “Conversations on Health Care,” which regularly features discussions on health policy and innovation with industry experts.

“We have addressed those, but what we have now is kind of a mess of a situation where more Americans are sick than healthy from diet-related diseases like obesity, diabetes and hypertension,” said Mozaffarian, Jean Mayer Professor at the Tufts Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy. “And at the same time, we have people who are food insecure.”

Mozaffarian is one of the co-chairs of an initiative that has been informing the White House conference on hunger and has produced a report with 30 policy recommendations. They include strengthening the existing federal nutrition programs such as WIC, accelerating access to “Food Is Medicine” services to prevent and treat diet-related diseases and establishing a new structure and authority within the federal government to coordinate various hunger, nutrition and health efforts across agencies.

Meanwhile, the COVID-19 pandemic has not only disrupted access to food for some, including children who relied on school lunches, it also has highlighted the link between diet-related diseases such as obesity and worse outcomes from a COVID-19 infection. Although average income and employment numbers have improved since 2020, “some U.S. households continue to face difficulties obtaining adequate food, particularly in the face of increasing food prices,” according to a report from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Nearly 30% of the world population — or 2.3 billion people — were food insecure in 2021, according to the United Nation’s report on the state of food security and nutrition, published in July 2022. That’s 350 million more people compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic began.

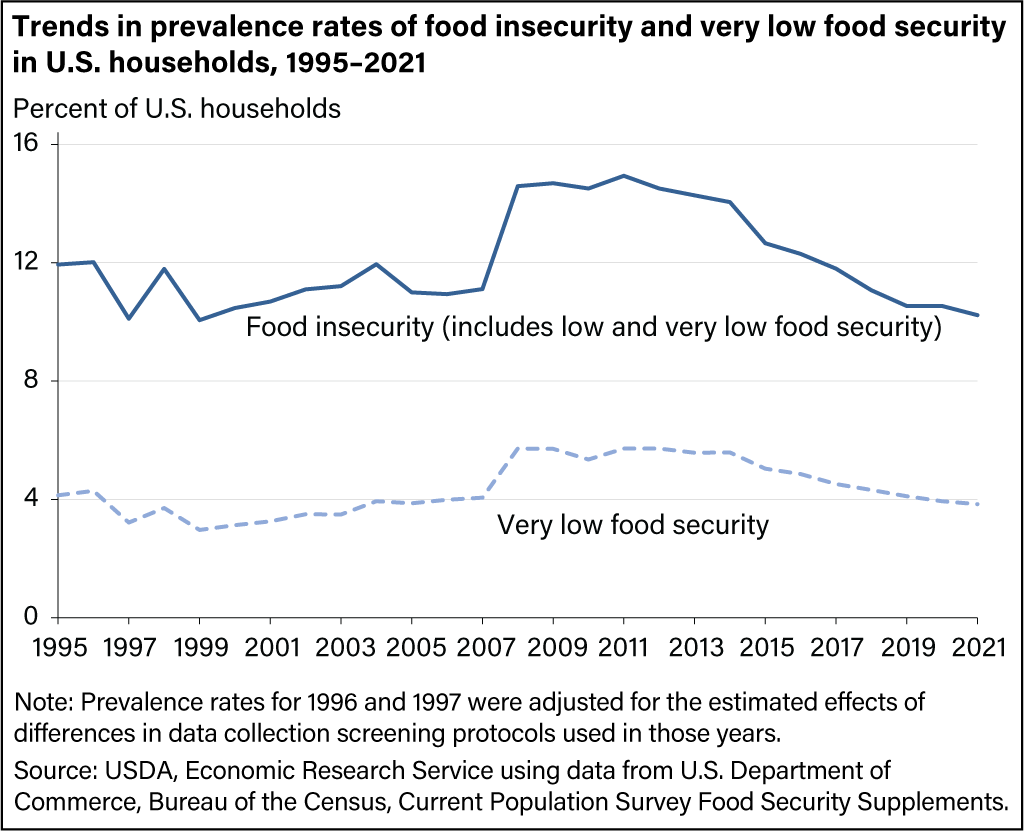

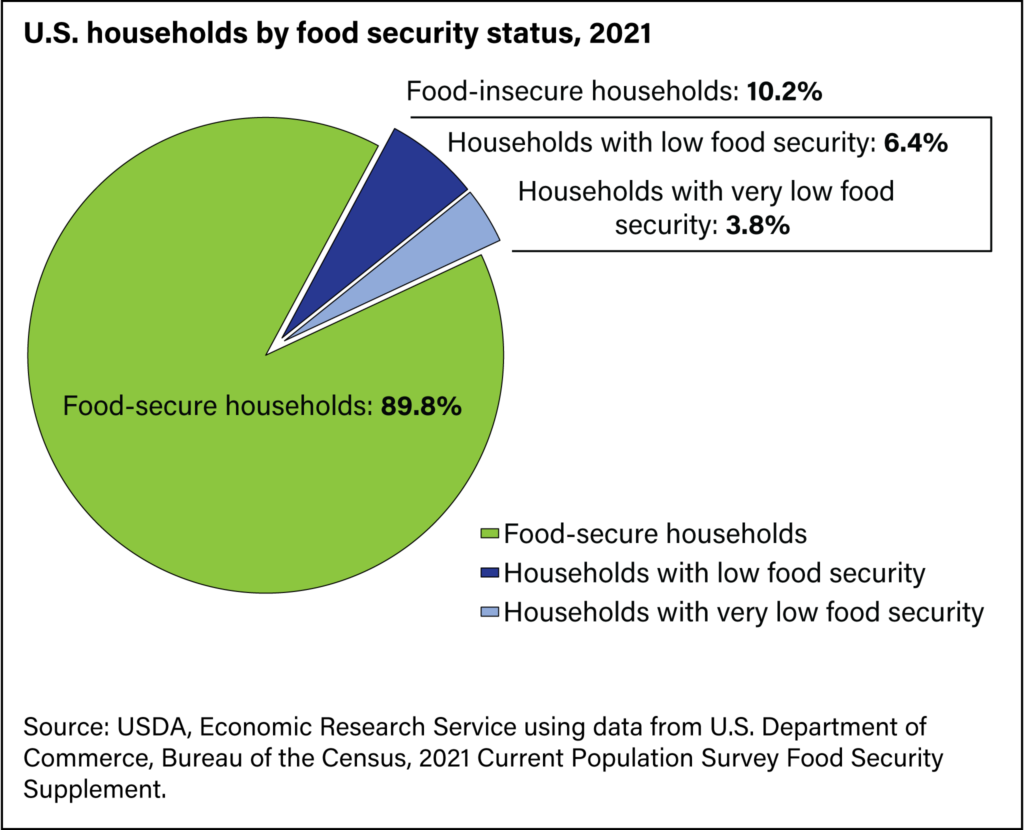

In the U.S., 10.2% of households were food insecure in 2021, which was not significantly different from 10.5% in 2020, according to the latest USDA data. The latest U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey, conducted between July and August 2022, shows that 11.5% of households reported sometimes or often not having enough to eat during the prior 7 days.

Food insecurity

The USDA defines food security as “access by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life.”

Food insecurity occurs when people have limited or uncertain access to healthy, affordable food because of a lack of money and other resources, according to the USDA. Food insecurity may be influenced by factors such as income, employment, race and ethnicity, and disability.

Food insecurity is considered one of the social determinants of health. It has been associated with higher rates of obesity, chronic diseases and developmental problems in children. Food insecurity can also affect mental health, studies show.

“Although having a chronic physical and/or mental health condition can be a precursor to food insecurity, research also shows that food insecurity itself causes considerable stress and anxiety, which can exacerbate pre-existing mental illnesses,” according to a June 2022 study from the United Kingdom, published in BJPsych Advances.

Food insecurity disproportionately impacts communities of color, people living in rural areas, people with disabilities, older adults, LGBTQ+ individuals, military families and veterans, said the U.S. Health and Human Services Assistant Secretary for Health Admiral Rachel L. Levine in a public video conference on Friday, Sept. 23, previewing the upcoming White House conference on hunger.

“No one should wonder where their next meal is coming from, or if they will have a safe opportunity to be physically active,” she said.

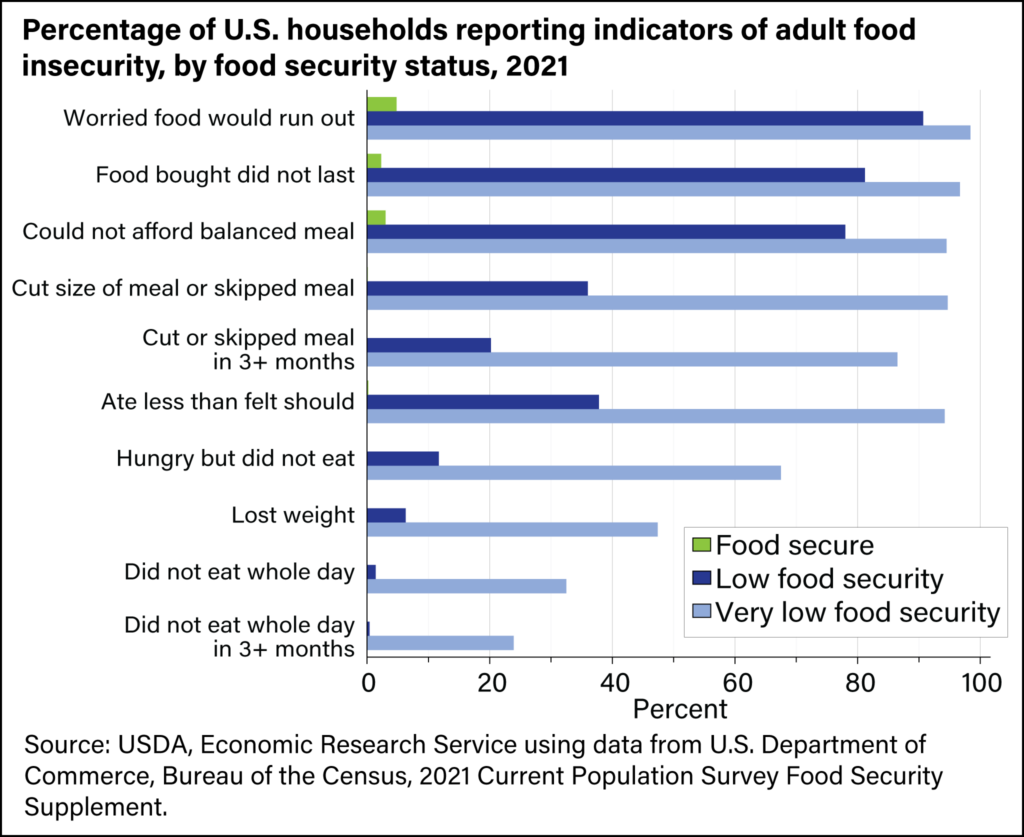

In 2006, the USDA introduced new terminology to describe American households’ access to food, ranging from “high” and “marginal” to “low” and “very low” food security. The low and very low food security levels are also described as “food insecurity.”

Food security levels are typically measured at the household level. The USDA monitors levels of food insecurity through an annual survey of U.S. households.

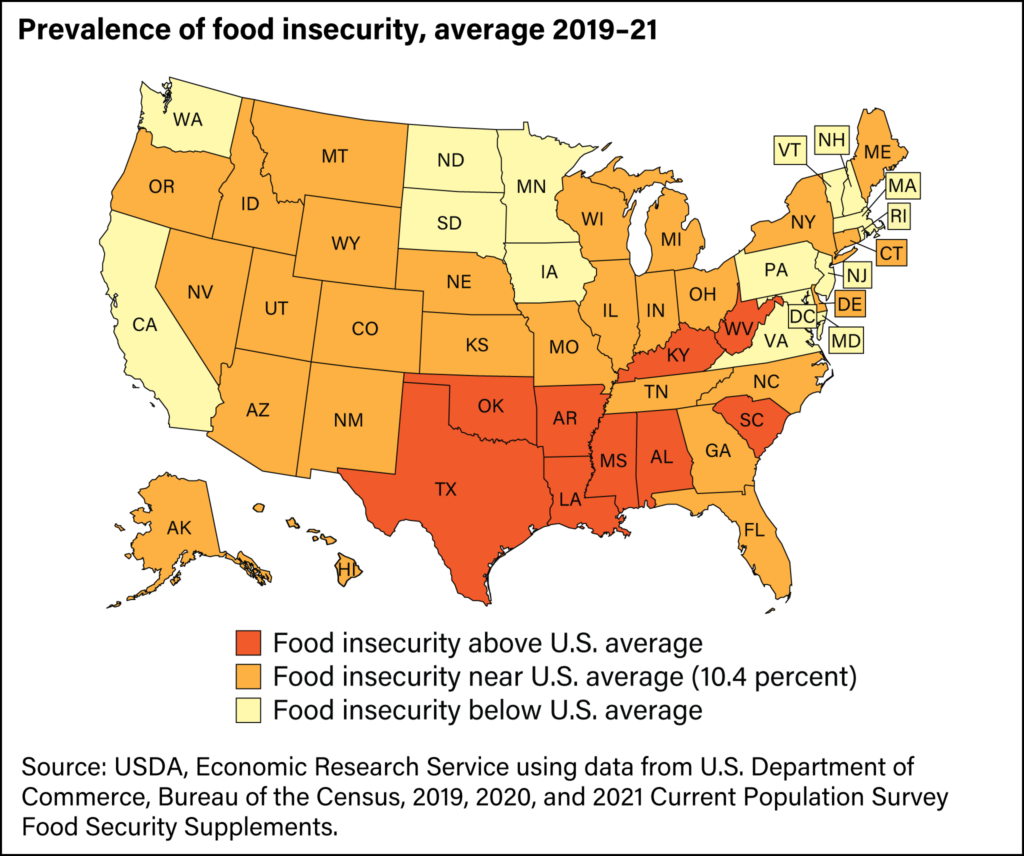

The agency’s 2021 survey, which included 30,343 households, finds 10.2%, or 13.5 million, U.S. households were food insecure and had difficulty at some points during the year providing enough food for everyone in the household due to lack of resources. The rate was 10.5% in 2020 and 2019. In total, 33.8 million people lived in food-insecure households in 2021. The reports also provide state-by-state data.

Rates of food insecurity were higher among certain groups, including single women with children, Black and Hispanic individuals, and households with income below the federal poverty line, which was $27,479 annually for a family of four in 2021.

Food security levels also vary by state, ranging from a low of 5.4% in New Hampshire to a high of 15.3% in Mississippi, according to the 2021 USDA report.

In the U.S., food assistance programs such as SNAP, WIC and the National School Lunch Program may help reduce food insecurity, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The U.S. rate of food insecurity is comparable to rates in other developed nations, although it is higher than some, including France, Germany, Austria and the United Kingdom, according to an analysis of 2019 data by Our World in Data, an organization that published research and data about world’s largest problems. Some of the highest rates of food insecurity are seen in parts of Africa, South America and the Middle East.

Food deserts

The term “food desert” was coined in the early 1990s by the Scottish Nutrition Task Force. Food deserts are defined as geographic areas where there’s a dearth of supermarkets, food retailers or other sources of healthy and affordable food. In many instances, these areas are low-income communities.

In its Food Access Research Atlas, the USDA maps food access indicators — mainly distance from supermarkets — in relation to poverty. Distance to food stores is measured in half-mile and 1-mile increments in urban areas and 10- and 20-mile increments in rural areas. For instance, a low income, low access area is where at least 500 people, or 33% of the population, lives more than one mile in an urban area or more than 10 miles in a rural area from the nearest supermarket, supercenter or large grocery store, according to the agency.

The agency also has a Food Environment Atlas, which examines how factors such as store or restaurant proximity, food prices, food and nutrition assistance programs, and community characteristics interact to influence food choices and diet quality.

Lack of access to healthy food options is associated with poorer health outcomes, studies have shown.

“A consequence of poor supermarket access is that residents have increased exposure to energy-dense food (’empty calorie’ food) readily available at convenience stores and fast-food restaurants,” according to the 2010 study “Disparities and Access to Healthy Food in the United States: A Review of Food Deserts Literature.” “It is documented that a diet filled with processed foods, frequently containing high contents of fat, sugar and sodium, often leading to poorer health outcomes compared to a diet high in complex carbohydrates and fiber,” the authors write.

Maintaining a healthy diet may be difficult for low-income people for several reasons. They may not be able to afford healthier options or lack transportation to a supermarket outside of their neighborhood.

“I think there are some people that make it seem like poor people are ignorant” about what healthy food choices are, said Dan Glickman, the former Secretary of Agriculture, in the video conversation including Mozaffarian and hosted by “Conversations on Health Care.” “And that’s just not true at all. There are certainly economic disincentives for them to be able to purchase, in many cases, fresh produce in the same capacities for the higher-income people.”

There have been efforts to bring healthy food options to underserved areas.

In 2010, former First Lady Michelle Obama’s “Let’s Move!” campaign announced the goal of eradicating food deserts by 2017, according to “Food Deserts: Myth or Reality?” published in the Annual Review of Resource Economics in October 2021. In 2011, the Healthy Food Financing Initiative (HFFI) was established at the Department of the Treasury and HHS. The 2014 Farm Bill – or the Agricultural Act of 2014 — officially established HFFI at the USDA. The program provides grants to community organizations to build or renovate grocery and retail food stores in underserved communities.

To be sure, bringing a supermarket to a low-income neighborhood isn’t going to quickly solve health problems like obesity, according to “The Changing Landscape of Food Deserts,” a report by the United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition released in June 2020. “However that new supermarket will probably have an impact on community health and well-being, including economic benefits,” the authors write.

About 10% of 65,000 U.S. census tracts are identified as food deserts by the USDA, affecting 13.5 million households.

Below, we have gathered several studies that examine the relationship between food insecurity and health. The list is followed by reporting resources for journalists. We will update this piece as new research and information becomes available.

Research roundup

The Effect of Food Access on Type 2 Diabetes Control in Patients of a New Orleans, Louisiana, Clinic

Jasmine A. Delk; et al. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association, September 2022.

The authors reviewed the records of 109 patients at a diabetes management clinic in New Orleans, Louisiana, and find that reduced proximity to grocery stores offering fresh foods may negatively affect patients’ ability to control their type 2 diabetes. The patients’ mean age was 54 years and 92% were Black. Six percent of the patients identified as “other or multiple races or ethnicities,” 1% were Native American/Pacific Islander and 1% were Asian. There were no white patients in the study group.

The study finds 79% of patients whose diabetes was uncontrolled — their blood glucose levels were above glycemic control standards — lived in food deserts.

“The results of this small, retrospective study serve as a beneficial starting point in raising awareness for the socioeconomic phenomena of food deserts and how these environments influence chronic disease state management,” the authors write.

Social Determinants of Health in Total Hip Arthroplasty: Are They Associated With Costs, Lengths of Stay, and Patient Reported Outcomes?

Ronald E. Delanois; et al. The Journal of Arthroplasty, July 2022.

The authors examine data from 136 Medicare patients at the Rubin Institute for Advanced Orthopedics at the Sinai Hospital of Baltimore, part of the Lifebridge Health network, who had an outpatient total hip replacement surgery between 2018 and 2019 to look for associations between social determinants of health — such as living in a food desert and having access to housing and transportation — and patient outcomes, including the costs of care during the 30 days after the procedure. The cost of care was defined as all costs of care after discharge, including physician payments. The mean age of the patients was 73 years and 60% were female. About 35% of the patients were “nonwhite,” and 40% of all patients reported living alone.

The authors find that the costs of care in the 30 days after the procedure were, on average, $53,600 more for people who lived in food deserts compared with those who didn’t live in a food desert. Other factors associated with increased costs included poor access to transportation and appropriate housing, and minority status, the authors find.

“As more [patients with total hip replacements] transition to the outpatient setting, social factors should play an increasing role in patient selection,” the authors write.

Disparities in Access to Food and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)-Related Outcomes: A Cross-Sectional Analysis

Eric Moughames; et al. BMC Pulmonary Medicine, April 2021.

The study links data collected from the SubPopulations and InteRmediate Outcome Measures in COPD Study between 2010 and 2015, and the 2019 food desert data using USDA’s Food Access Research Atlas. Of the 2,713 patients in the dataset, 22% lived in food deserts. Those living in food deserts were more likely to be “nonwhite” and more likely to have a lower income than those who didn’t live in food deserts, according to the study.

The authors find living in a food desert area was associated with worse chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or COPD, outcomes. They also find limited food access is detrimental in both low- and high-income neighborhoods. The connections between low food access and COPD outcomes were stronger in urban areas compared with rural areas.

“The results further suggest that the impact of low food access may be greatest in urban areas,” they write. “Our results could be explained by the ubiquitous prevalence of unhealthy options (e.g., corner stores, fast food chains, etc.) in cities compared with rural areas, and in this type of urban setting, people will be more inclined to go to a fast food restaurant or corner store that is much closer and cheaper rather than walking farther away to a healthy food source.”

Related study: “Evaluating the Association Between Food Insecurity and Risk of Nephrolithiasis: An Analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey,” by Benjamin W. Green; et al., published in the World Journal of Urology in September 2022, finds a relationship between food security and developing kidney stones, with greater severity of food insecurity associated with increased risk of developing kidney stones.

Food Deserts and Cardiovascular Health among Young Adults

Alexander Testa, Dylan B. Jackson, Daniel C. Semenza and Michael G. Vaughn. Public Health Nutrition, July 2020.

The authors analyze data from Wave I (1993–1994) and Wave IV (2008) surveys from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, including 8,896 study participants between 24 and 36 years old. They find living in a food desert was associated with poorer cardiovascular health. They also find living in a food desert has the strongest association with greater cigarette use.

“One possibility is that engagement in worse health behaviors via living in a food desert may be a partial function of the composition of the type of retail outlets in the area,” the authors write. “For instance, food deserts tend to have a larger composition of unhealthy retailers that sell cigarettes and advertise the sale of tobacco products on store fronts (such as convenience stores or neighborhood bodegas), which may translate into poorer health behaviors.)”

Related study: “Association Between Living in Food Deserts and Cardiovascular Risk,” by Heval M. Kelli; et al., published in Circulation Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes in September 2017, finds that among 1,421 people living in the Atlanta metropolitan area, those living in food deserts had higher prevalence of high blood pressure, smoking, obesity and 10-year risk for cardiovascular disease.

Food Insecurity and Loneliness Amongst Older Urban Subsidised Housing Residents: The Importance of Social Connectedness

Judith G. Gonyea, Arden E. O’Donnell, Alexandra Curley and Vy Trieu. Health and Social Care in the Community, September 2022.

The authors use survey data from in-person interviews in English or Spanish with 216 adults ranging in age from 55 to 90 years and living in a subsidized housing community in a neighborhood of a U.S. northeastern city. Half of the participants were Black and 45% were Latino.

Researchers find that 34% survey respondents reported being food insecure, which is higher than the 10% average for the older adults in the U.S. About 34% of the respondents also reported being lonely, which is higher than the 19% to 29% average for older adults nationally.

“The present study offers evidence of the interrelatedness of food insecurity, loneliness, poor health and food access challenges for the understudied population of lower-income older adults living in subsidized housing communities,” the authors write. “Importantly, the current study underscores the need to investigate the role of social and emotional factors that may heighten the risk of individuals experiencing food insecurity in later life.”

More studies of note

- “The 1969 White House Conference on Food, Nutrition and Health: 50 Years Later,” by Eileen Kennedy and Johanna Dwyer, published in Current Developments in Nutrition in June 2020, provides a historical overview of the first conference and the programs that were developed as a result. “Necessary ingredients such as policy-relevant science, leadership, advocacy, and the science and art of politics must be blended together to make nutrition policies that truly advance the public’s health and well-being,” the authors write.

- “Association of Socioeconomic and Geographic Factors With Diet Quality in US Adults,” by Marjorie L. McCullough; et al., published in JAMA Network Open in June 2022, examines data from 155,331 adults participating in a nationwide U.S. cohort study. The researchers find that Black individuals, low-income white individuals, those with low levels of education (high school or lower), and people living in rural areas or food deserts, were more likely to have overall poor diet quality. “All dietary components, but especially sugar-sweetened beverages and processed meats, contributed to the disparities observed,” the authors write. “Higher income and education had protective associations against poor diet quality, but these associations were not the same across all racial and ethnic groups.”

- “Measuring the Food Environment and Its Effects on Obesity in the United States: A Systematic Review of Methods and Results,” by Ryan J. Gamba, Joseph Schuchter, Candace Rutt and Edmund Y. W. Seto, published in Journal of Community Health in October 2014, examines 51 peer-reviewed studies that analyzed the relationship between obesity and the number, type and location of food outlets such as supermarkets, convenience stores and fast-food restaurants. It finds that 80% of the studies found at least one significant association between the food environment and obesity. “Although the methods and results of individual studies were inconsistent, as a whole this body of research suggests that food environments are associated with obesity,” the authors write.

- “Food Insecurity Among People With Cancer: Nutritional Needs as an Essential Component of Care,” a commentary by Margaret Raber; et al., published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute in September 2022, notes that 17% to 55% of the cancer patients in the U.S. are food insecure. The commentary “explores the issue of food insecurity in the context of cancer care, explores current mitigation efforts, and offers a call to action to create a path for food insecurity mitigation in the context of cancer.”

- “Food insecurity Among African Americans in the United States: A Scoping Review,” by Elizabeth Dennard; et al., published in PLOS One in September 2022, aims to identify risk factors associated with food insecurity and how food insecurity is measured across studies that focus on African Americans. In their conclusion, the authors write, “underrepresented risk factors to consider for future research include factors linked to health disparities among African American adults: lifetime racial discrimination, neighborhood grocery store availability, neighborhood safety from violence, income insecurity, and the impact of COVID-19 on employment.”

- “The Economics of Food Insecurity in the United States,” by Craig Gundersen, Brent Kreider and John Pepper, published in Autumn 2011 in Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, provides an in-depth review of food insecurity, including the nuanced relationship between income and food security and the impact of food assistance programs on food insecurity.

- “Food Insecurity and Severe Mental Illness: Understanding the Hidden Problem and How to Ask About Food Access During Routine Healthcare,” by Jo Smith; et al., published in BJPsych Advances in June 2022, provides an overview of the relationship between food insecurity and mental illness, and its impact on people with severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. “Psychiatrists need to routinely assess and monitor food insecurity in people with [severe mental illness],” the authors write.

- “Changes in Food Environment Patterns in the Metropolitan Area of the Valley of Mexico, 2010–2020,” by Ana Luisa Reyes-Puente; et al., published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health in July 2022, looks at “food swamps,” which are areas where residents have easy access to high-calorie food, so much that the supply overshadows healthy food options. “The proliferation of food swamps is a feature of food environments in the global south. Unlike food deserts in the global north, where solving physical access to healthier food suffices to regulate its effect on malnutrition, in food swamps in the global south, solutions must be geared towards solving physical access as well as the social preferences of the population for certain types of food,” the authors write.

- “A Descriptive Analysis of Food Pantries in Twelve American States: Hours of Operation, Faith-Based Affiliation, and Location,” published in BMC Public Health in March 2022, provides an overview of food banks and finds that in the 12 states studied, “approximately three quarters of food pantries are located in urban areas, and almost two thirds were considered to have a faith affiliation, which were also more common in urban versus rural areas.”

- “Mobile Pantries Can Serve the Most Food Insecure Populations” by Lily K. Villa; et al, published in Health Equity in January 2022, uses data from an Arizona food pantry called the Phoenix Rescue Mission and finds “people aged 60-80 years and immigrant people of color are more likely to use both mobile and brick-and-mortar pantries.” The mobile pantries in this study are an extension of the brick-and-mortar food pantry operation and are vans that can change locations to meet the residents’ needs. The authors write: “This research suggests that mobile pantries can reach the most food insecure populations and local nonprofits and governments can consider implementing mobile pantries to reach food insecure communities.”

- “An Equity-Oriented Systematic Review of Online Grocery Shopping Among Low-Income Populations: Implications for Policy and Research,” published in Nutrition Reviews in May 2022, examines 16 studies that assessed various aspects of online grocery shopping. It finds low availability of online grocery services in rural communities, high costs, and perceived lack of control over food selection were important barriers to using online grocery services. Meanwhile, factors such as the ability to pay for groceries online with SNAP benefits were motivators. (Related studies: “Online Pilot Grocery Intervention among Rural and Urban Residents Aimed to Improve Purchasing Habits,” and “Availability of Grocery Delivery to Food Deserts in States Participating in the Online Purchase Pilot.”)

More recommended sources

- “Conversations on Health Care” hosts Mark Masselli and Margaret Flinter speak with Dan Glickman, the former Secretary of Agriculture, and Dr. Dariush Mozaffarian, a renowned expert on food systems, about the White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health, on Sept. 22, 2022. The program features in-depth discussions on health policy and innovation with industry newsmakers.

- “The White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition and Health is an opportunity for transformational change,” by Dariush Mozaffarian; et al., published in Nature Food in August 2022, provides historical context and the authors’ hopes for the 2022 White House conference on hunger.

- “USDA Food Box Program: Key Information and Opportunities for Better Access to Performance,” published in September 2021 by the U.S. Government Accountability Office, evaluated the Food Box Program, which was implemented by the USDA in May 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The program paid contractors to buy food from producers and deliver it to organizations like food banks, according to GAO.

- “Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Food Insecurity in the United States,” by David H. Holben and Michelle Berger Marshall, published in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics in October 2022, states, “systematic and sustained action is needed to achieve food and nutrition security in the United States.” It adds: “To build and sustain solutions to achieve food security and promote health, [registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs), and nutrition and dietetics technicians, registered (NDTRs)] should engage in outreach efforts to forge partnerships among clinicians, charitable food providers, community partners, food processors, food retailers, other stakeholders, and people living with food insecurity.”

Resources for journalists

- You can sign up here to watch the White House conference, which will be livestreamed on Sept. 28, 2022 at 9 a.m. EST.

- “Food Security in the U.S.” is the USDA’s main online source for data and information on the topic. It also has a helpful “Media Resources” page, which includes tips for interpreting food security statistics.

- You can use the USDA’s Food Access Research Atlas to find food access indicators for low-income areas using different measures of supermarket accessibility at the census tract level. A census tract is a small, relatively permanent subdivision of a county that usually contains between 1,000 and 8,000 people but generally averages around 4,000 people. You can also find state-by-state estimates of the size of low-income populations who have low access to nutritious food here.

- The USDA’s Food Environment Atlas provides maps and data on restaurant proximity, food prices, food and nutrition assistance programs and community characteristics. One of the Atlas’ goals is “to provide a spatial overview of a community’s ability to access healthy food and its success in doing so.”

- The USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service has data and reports on child nutrition and programs, including SNAP and WIC.

- You can find the USDA’s annual reports on household food security, dating back to 1995, here.

- Our World in Data has several charts that compare countries’ levels of hunger and undernourishment.

- The Center for Science in the Public Interest is an independent, science-based consumer advocacy organization and a food and health watchdog.

- Feeding America is a nationwide hunger-relief organization with a network of 200 food banks and 60,000 food pantries and meal programs.

Expert Commentary