One day in January 2022, Associated Press reporters Michael Balsamo and Michael Sisak were sitting at a Starbucks on Long Island, where they both grew up, planning their investigation into the nation’s prison system, when Sisak got a message from a long-time source asking him if he had heard about the resignation of Michael Carvajal, who had been the director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons since 2020.

Less than two months before, the two had published a story revealing that more than 100 federal prison workers had been arrested, convicted or sentenced for crimes since 2019, a number much higher than in other law enforcement agencies. In response, the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee had called on the U.S. Attorney General to fire Carvajal. And now Carvajal was resigning.

The reporting duo had been laser-focused on the Bureau of Prisons since 2019, after Jeffery Epstein, the high-profile American financier who was accused of sex trafficking, was found dead in his Manhattan jail cell.

It “was a stark reminder that this agency exists,” says Sisak, a prisons and law enforcement reporter based in New York. “[It] exposed a lot of failures within the agency and Mike and I said, ‘What else can we look at?’ Staffing, abuses, all of these institutional things that were happening in New York City and all across the country.”

Their continued investigation into the Bureau of Prisons in 2022 exposed systemic corruption and abuse.

They revealed systemic sexual assault at a federal women’s prison in Dublin, California. The abuse was so rampant that staff and inmates called it the “rape club.” As a result of the reporters’ stories, several staff members, including the former warden, were charged with sexually abusing inmates and a handful of others were placed on leave.

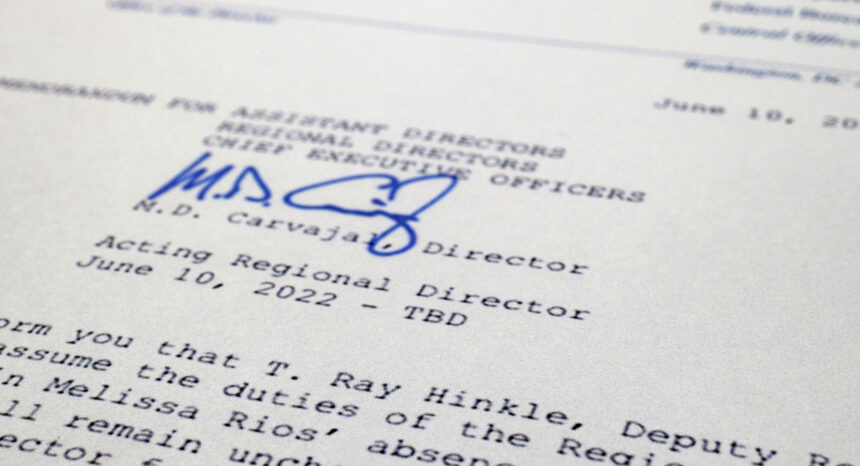

Balsamo and Sisak’s investigations culminated in a story in December 2022, detailing how Thomas Ray Hinkle, an acting warden who was sent to restore order and trust at the women’s prison in Dublin, had bullied whistleblowers for exposing wrongdoings, stonewalled a member of Congress who visited the prison in response to AP’s reporting, and had been accused by at least three inmates of beating them as part of a violent, racist gang of officers in the 1990s — and yet was promoted over and over again. (The Bureau of Prisons defended Hinkle in the AP story, saying “he’s a changed man and a model employee.”)

As a result of their reporting:

- Sen. Jon Ossoff, the chairman of the U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, launched a series of hearings, which highlighted the duo’s reporting, and issued a subpoena to compel Carvajal to appear before the panel when he refused.

- Ossoff, a Democrat from Georgia, also introduced legislation after the AP’s reporting and watchdog reports to compel the Bureau of Prisons to fix their broken cameras. President Joe Biden signed the bill into law in December 2022.

- And Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, read, line for line, the AP stories into the congressional record and has held several hearings on the Bureau of Prisons based on AP’s reporting.

The Federal Bureau of Prisons, or BOP, is the largest law enforcement agency under the department of Justice, with more than 34,000 employees, 158,000 inmates and a budget of over $8 billion.

“But it doesn’t have the cachet that [other law enforcement agencies] like the FBI have,” says Sisak. “We’re trying to bring the spotlight in our reporting to an institution that people don’t have top of mind, even though it is having a huge impact on hundreds of thousands of people and communities across the country.”

It is also one of the only Justice Department agencies where the head of the agency is not confirmed by the U.S. Senate and is instead appointed by the U.S. Attorney General.

“And it’s an agency that has had no oversight for years,” says Balsamo, U.S. law enforcement news editor for the AP.

Below, Balsamo and Sisak share several tips for journalists who want to investigate a large federal agency like the Bureau of Prisons.

1. Cultivate sources, stay in touch and listen.

“Sources beget sources,” Sisak says. “You talk to one person, and they put you in touch somebody else. You get an email then you do a story about Dublin now you’re getting emails from people that also have experiences with Dublin. It’s just being out there and being present.”

It was one Sisak’s sources from a decade ago that tipped him off about Carvajal’s resignation.

“You might talk to somebody at a press conference — jot their name down and stay in touch with that person,” says Sisak. Down the road, “they’re going to know stuff that you might need.”

2. When schedules and funds allow it, show up in person and wait.

In response to the AP’s reporting, the Justice Department had set up a task force to go to Dublin, California, in March 2022. The prison officials “really didn’t want us to be there,” says Balsamo.

He and Sisak decided to go there anyway during the week that the task force was there.

“We told them that we’re going to be in Dublin the entire week and if the director wants to talk to us, great; if not, we’re going to be there to talk to people and find out what happens,” says Balsamo.

Once they arrived, they let their existing sources know they were there and asked if they wanted to meet. Some were people who had been talking to them on phone of email for months and this would their first in-person meeting.

“And when you’re sitting in a restaurant and have a face-to-face interaction, it’s a much easier [conversation] because people feel more comfortable,” said Balsamo.

It was in one of their in-person meetings that March, at a McDonald’s and 45 minutes into the conversation, when a source told them they should look into Dublin’s acting warden Hinkle.

3. Tell your audience about your investigation and involve them in your reporting process.

The reporting duo published two stories headlined “The story so far”, one in May 2022 and one in December 2022, to keep readers updated on the progress of their investigations and encouraged them to send in tips — sharing their email addresses at the end of the stories.

“I think putting your name out there and flying the flag and saying AP is interested in this thing that a lot of people aren’t interested in, is so helpful,” says Sisak. “For reporters out there, maybe it’s a local police department or it’s a jail. Start telling people ‘Hey, I’m interested in this topic.’ People are going to come forward. People want to talk.”

4. Be aware of possible retaliation against your sources and report it when it happens.

“When we’re talking to incarcerated people, there’s a real threat for them,” says Balsamo.

Learn the jail or prison guidelines for inmate communication with the media. For instance, incarcerated people in federal prisons can send letters marked “Special Mail” to certain government offices and members of the news media, which are not supposed to be read by the Bureau of Prisons. But the agency staff can open the incoming mail, including responses to those letters. Also, all emails are monitored by the agency.

“Figure out the best way to interact with them, either through their lawyers or through other methods so that you are limiting the risk,” says Sisak. “It’s like the medical [phrase], ‘First do no harm.’ It’s our goal to do no harm to people.”

There were retaliations in prisons against some of their sources, including the staff and incarcerated individuals. Some inmates were put in “restricted housing,” — the Bureau of Prisons’ version of solitary confinement — after they spoke with the AP reporters. And Balsamo and Sisak wrote about it.

“We took the approach of if you’re going to come after people because they’re talking to us, we’re going to write about that and we’re going to ask you why you’re doing that,” said Balsamo.

5. And if your public records requests are denied without reason, tell your audience about that too.

In addition to denying many of AP’s records requests, the the Bureau of Prisons also denied their request for a photo of Hinkle.

The reporters wrote in their December 2022 story: “The AP also filed requests with the Bureau of Prisons under the Freedom of Information Act for background information on Hinkle, including his job history, work assignments and official photograph. The agency claimed it had ‘no public records responsive’ to AP’s request.

The agency also denied a request for Hinkle’s disciplinary records, saying that ‘even to acknowledge the existence of such records … would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of personal privacy.’”

6. For old federal court cases, try the National Archives.

Balsamo and Sisak learned about a lawsuit filed in the mid-1990s, where Hinkle was a defendant, but they couldn’t find it in PACER, the Public Access to Court Electronic Records, because the case was too old.

They knew the case number from a story in Prison Legal News, a project of the Human Rights Defense Center. So they contacted the courthouse in Denver, where the case was filed, and obtained details and numbers they needed to request the material from the National Archives and Records Administration, which keeps important legal and historical documents and materials created by the U.S. federal government. For a fee, the National Archives scanned the file’s 1,600 pages and sent it to them.

7. In team reporting, be in constant communication.

Balsamo and Sisak each had their own set of sources. While Balsamo mainly covered the Justice Department, Sisak had sources at prisons across the country.

“We tried to divvy up the reporting responsibilities. We were talking constantly and that’s the most important thing — communication with your beat partner,” says Balsamo.

8. Write down tips, and keep the emails.

If you’re at a press conference, focused on covering one story, and you hear about three other tips or story ideas, write them down right then so you won’t forget to follow up on them, says Sisak.

“Write it down and keep on top of it. Keep asking about it,” says Sisak.

Sisak has a folder in his email inbox for federal prisons, where he saves the tips he gets.

“Maybe the thing in Beaumont, Texas, is not a story today, but it’s going to fit into a story in a month,” he says. “Keep that information and reassure people that you’re interested in the topic, not necessarily making promises but letting them know that you’re interested in telling the grand story.”

9. If you’re intimidated by the big story, then approach it one small story at a time.

“Chipping away is a really good approach,” says Balsamo. “Do the smaller stories, build sources. Each story led us to the next story.”

Sisak encourages journalists to keep pushing even if the task seems impossible, like penetrating the walls of the Bureau of Prisons.

“We’re two guys from Long Island and we’ve shown that it’s possible to do that,” he says.

Read their stories:

- US prisons director resigning after crises-filled tenure

- AP investigation: Women’s prison fostered culture of abuse

- Whistleblowers say they’re bullied for exposing prison abuse

- ‘Abhorrent’: Prison boss vexes DOJ with alleged intimidation

- AP investigation: Prison boss beat inmates, climbed ranks

Correction: An earlier version of this piece described the reporting duo having coffee “in” Long Island. The correct preposition is “on” Long Island, according to the AP Stylebook and other guides, including Grammarphobia. Special thanks to those who corrected us on Twitter. We regret the error.

Expert Commentary