American Indian and Alaska Native populations have substantially higher death rates across age groups and the lowest average life expectancy compared with white, Black and Hispanic populations in the U.S., according to a recent study by researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The study also shows that 34% of non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native deaths are misclassified as a different race on death certificates, leading to underestimation of deaths in this population.

The findings in “Mortality Profile of the Non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native Population, 2019,” published as a National Vital Statistics Report in November 2021, confirms what previous studies have shown and are a reminder of stark and persisting health disparities in the AIAN population.

“My hope is that policymakers and health care providers recognize the very large disparity between this population and all other populations in this country,” says Elizabeth Arias, a health scientist at the National Center for Health Statistics and the lead author of the study. “They have the worst health profile and mortality risk in this country. So, I would call it an emergency. It is something that should be taken very seriously.”

The study is distinctive in that it looks at the entire AIAN population in the U.S. using data from the 2010 decennial census. Previous studies have used data from the Indian Health Service, a federal agency that provides health care for federally recognized tribes, or 64% of the AIAN population, hence not accounting for individuals who consider themselves American Indian or Alaska Native but are not members of those tribes.

The AIAN population defined as American Indian or Alaska Native alone and not in combination with another race, was 1.1%, or 3.7 million, of the total population living in the U.S., according to the latest census data. An additional 5.9 million people identified as American Indian and Alaska Native and another race group in 2020. Arias and her colleagues analyzed records for those who were American Indian or Alaska Native alone, were not Hispanic and didn’t list any other races.

Misclassification of race and ethnicity on death certificates

But there’s a dearth of published national death statistics for the AIAN population. One of the main reasons for poor quality data is the misclassification of race and ethnicity on death certificates, Arias and her colleagues note.

The classification of race and ethnicity on death certificates is usually the responsibility of funeral directors who gather information from next of kin or by relying on observation alone, researchers explain.

They find that 34% of non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaska Natives were misclassified as a different race on death certificates. About 28% of were misclassified as white, making it the most common misclassification, they report. Four percent were misclassified as Black, and less than 1% as Asian or Pacific Islander.

“So, when you produce death rates, which are based on information from the death certificates and population estimates from the Census Bureau, you get death rates that are too low because you’re missing a lot of deaths that are misclassified,” Arias says.

In comparison, death certificate misclassification for white, Black and Hispanic populations is negligible, the authors note.

To account for misclassification of race and ethnicity on death certificates, and to get a better estimation of the true number of deaths among AIAN individuals, researchers match datasets that include AIAN individuals’ data with the National Vital Statistics System’s mortality data, which analyzes approximately 2.8 million records each year to produce information on death and its causes in the U.S.

Arias and her colleagues used the 2010 decennial U.S. census records for everyone who identified as AIAN. They then matched identifying factors such as name, birth date and social security number with the National Vital Statistics System’s mortality data to calculate the percentage of AIAN deaths that were misclassified in the mortality database.

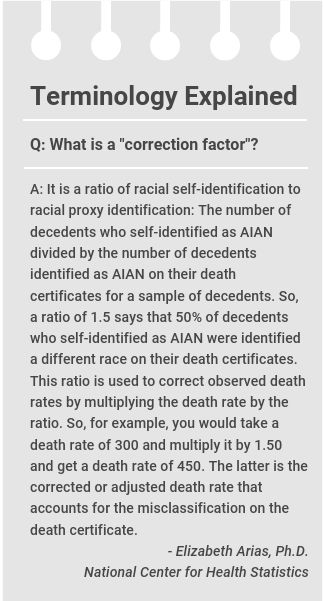

They then used the resulting “correction factor,” which is 34%, to create more accurate estimates of life expectancy and death in the AIAN population.

The correction factor produced from the study can be used in future analyses, Arias says.

“The correction factors are consistent with what we have seen from prior studies, going all the way back to the 1980s,” she says. “What that tells us is that the misclassification has been pretty constant and hasn’t changed that much.”

The research team’s goal is to continue to expand on their work and eventually use data from the 2020 decennial census, which is still being finalized. National data show that the AIAN population has experienced one of the highest rates of COVID-19 cases and deaths compared with other races and ethnicities in the U.S. since the pandemic began in 2020.

The study’s findings

After adjusting for the misclassification of deaths, Arias and her colleagues estimate that 24,113 AIAN individuals died in the U.S. in 2019. The death rate for this population was 40% higher than the rate non-Hispanic whites, 17% higher than that of the non-Hispanic Black population, and 98% higher, or almost two times greater than, that of the Hispanic population.

At 71.8 years, AIAN individuals have the lowest life expectancy compared with other races and ethnicities. Life expectancy was 78.8 years, on average, for white people, 74.8 years for Black people, and 81.9 years for Hispanic individuals.

The average life expectancy of AIAN individuals calculated by Arias and colleagues is lower than the 78.4 years reported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Minority Health, which uses Census Bureau projections.

The AIAN population also have a higher death rate than white, Black and Hispanic populations across most age groups. AIAN men have higher death rates than AIAN women in all age groups, except for 85 and over, Arian and her team find.

The study shows AIAN individuals have higher death rates for most of the top leading causes of death and in most age groups compared with white, Black and Hispanic people. The 15 leading causes of death, including heart disease, cancer, accidental injuries, diabetes and hypertension, accounted for 79% of all deaths among AIAN individuals. The top two leading causes of death — heart disease and cancer — accounted for 37% of all deaths.

There were notable disparities in certain causes of death. For instance, the death rate from suicide was four times higher for AIAN individuals compared with Hispanics. The AIAN death rate from homicide was five times higher than whites. Meanwhile, the rates of death from heart disease and cancer were similar to Black individuals. AIAN individuals’ rate of death from homicide was one-half of the rate for the Black population.

The study has two main limitations. It doesn’t include Hispanic AIAN individuals, who make up a small segment of the population, which includes people who are indigenous to the Americas, like indigenous Mexican, Central American or South American people. However, the authors believe estimates currently produced by the Census Bureau overestimate the number of Hispanic AIAN individuals. Also, indigenous people who come from Latin America are most likely not familiar with the race and ethnicity construct in the U.S. and may not realize that the Census Bureau considers them American Indian or Alaska Native. They study also doesn’t include census records that didn’t have social security numbers. That could lower the match rate between databases, the authors write.

What other studies show

Some of the recent studies that match two datasets to calculate the misclassification of deaths were done in 2014, when a CDC research team matched Indian Health Services data with the National Vital Statistics System’s mortality data for the years 1990 to 2009, creating the AIAN Mortality Database.

One study from that analysis, “Leading causes of death and all-cause mortality in American Indians and Alaska Natives,” published in the American Journal of Public Health in April 2014, shows higher rates of deaths from any cause among the AIAN population compared with white, Black and Hispanic groups.

The study, authored by CDC epidemiologist Melissa Jim and colleagues, shows that the rates of death from any cause among the AIAN individuals was 46% higher than for whites. They also show that deaths from any cause among younger AIAN individuals, between 25 and 44 years old, was nearly three times higher than for white people in the same age group.

Another study shows that the misclassification of deaths varies widely by geography. Jim and colleagues published “Methods for Improving the Quality and Completeness of Mortality Data for American Indians and Alaska Natives,” in June 2014 in the American Journal of Public Health, showing that the misclassification of AIAN mortality data ranged from 6.3% in the southwestern U.S. to 35.6% in the Southern Plains.

In June 2014, Arias, Jim and colleagues authored, “Period Life Tables for the Non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native Population, 2007–2009,” published in the American Journal of Public Health, finding that the AIAN population have the lowest average life expectancy of 71.1 years, compared with other racial and ethnic groups in the U.S.

Arias and Jim co-authored another study in June 2014, “Racial Misclassification of American Indians and Alaska Natives by Indian Health Service Contract Health Service Delivery Area,” published in the American Journal of Public Health, evaluating the racial misclassification in national cancer incidence and in data for deaths from any cause. They find that “racial misclassification is a widespread problem for the AI/AN population.”

Misclassification in cancer rates

Jim, who is Diné from the Navajo Nation, and an epidemiologist with the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control at the CDC, has been focusing her recent work on identifying misclassification of cancer cases in the AIAN populations in order to establish better estimates.

When AIAN individuals are diagnosed with cancer, they often get referred out of the Indian Health Services’ system, because the system mostly provides primary care, Jim explains. Cancer data collected outside Indian Health Services by various cancer registries sometimes misclassifies AIAN individuals. The misclassification can result in the underreporting of cancer cases among AIAN individuals, preventing federally recognized tribes from receiving federal funding for efforts like cancer prevention, Jim says. More accurate data also helps tribes better understand health trends among their members.

The team also regularly produces data briefs and research about cancer incidence in the AIAN population.

In a study published in the American Journal of Epidemiology in October 2020, Jim and her co-authors report that between 2012 and 2016, American Indians and Alaska Natives were more likely to get liver, stomach, kidney, lung, colorectal, and female breast cancers than white people in most regions of the country.

The coronavirus pandemic has also highlighted the continuing disparities affecting the AIAN population.

“COVID-19 Among American Indian and Alaska Native Persons — 23 States, January 31 – July 3, 2020,” published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, shows that, in 23 states with adequate race and ethnicity data, the rate of COVID-19 cases among AIAN individuals was 3.5 times higher than non-Hispanic white individuals.

Expert Commentary