This piece on maternal mortality was updated on September 19, 2022, to reflect new data from the CDC.

Each year, at least 700 women die in the United States because of pregnancy or delivery complications. Four in five of those deaths are preventable, according to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

These deaths are defined as maternal mortality or pregnancy-related deaths. The maternal mortality data are typically reported as rates, which is the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births.

Worldwide, the maternal mortality rate was estimated at 211 in 2017. The World Health Organization’s goal is to reduce that rate to 70 by 2030.

The U.S. maternal mortality rate is 23.8, according to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s considered “very low” globally, yet it is far higher than many other wealthy nations including Sweden, Italy, Austria and Japan.

To be sure, the U.S. maternal mortality rates dropped steadily throughout the 20th century, from over 800 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1900 to 6.6 per 100,000 in 1987. The decline was attributed to several factors, including better disease monitoring, access to health care, better nutrition and advances in medicine.

But since then, the rate has been steadily increasing. By 2018, the maternal mortality rate was at 17.3 per 100,000, then at 20.1 in 2019 and 23.8 in 2020, according to the CDC. Factors contributing to the increase include disparities in access to care, increasing maternal age and increase in chronic conditions such as diabetes and obesity, studies show.

In June, the White House released a Blueprint for Addressing the Maternal Health Crisis, with a vision that the U.S. “will be considered the best country in the world to have a baby” in the future. Among the first steps is improving and expanding Medicaid coverage, better data collection, diversifying the perinatal workforce and providing better economic and social support for people before, during and after pregnancy.

Disparities in maternal mortality

There are stark and persisting racial disparities in maternal mortality in the U.S. Black people are more than three times as likely as white women to die from pregnancy-related causes, according to the CDC. American Indian and Alaska Native people are more than twice as likely.

Between 2018 and 2020, the maternal mortality rate for Black people was 55.3, compared with 19.1 among white people and 18.2 among Hispanic people, according to the latest CDC data.

In comparison, the maternal mortality rate was 41.4 among Black people, compared with 13.7 for white people between 2016 and 2018. The rates were 26.5 for American Indian or Alaska Native people, 14.1 among Asian or Pacific Islanders and 11.2 for Hispanic people, according to the CDC.

While factors such as access to care and health insurance coverage play a role in pregnancy outcomes, research also points to disparities in social determinants of health such as income, age and housing. Many of these disparities are related to systemic and structural racism.

“It’s important to be clear that it’s racism, not race,” says Dr. Rachel Hardeman, Blue Cross Endowed Professor of Health and Racial Equity at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health, and the founding director of the Center for Antiracism Research for Health Equity at the University of Minnesota. “It’s about systems and structures that historically have been built to not ensure that Black people and Black working people thrive.”

And until structural racism and related factors such as implicit bias in health care are addressed, “we will continue to see the disparities,” says Dr. Veronica Gillispie-Bell, associate professor at Ochsner Clinical School and head of Women’s Services at Ochsner Medical Center in Kenner, Louisiana.

Advice for journalists

For journalists covering the issue, especially after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June and in light of the upcoming midterm elections, it’s important to explain what’s driving current disparities in maternal mortality and how abortion bans can potentially worsen those disparities.

“When we are forcing people to remain pregnant, that means statistically speaking, there are more people who will be pregnant in the United States because Roe has been overturned, which means there are more people in that risk pool for adverse outcomes,” says Hardeman.

The state bans also adversely affect people with fewer resources because they are less likely to have the ability to travel to states where abortion remains available.

“That means you have to have a job that offers paid leave. It means you have to have childcare. It means you have to have the resources to drive, to fly, to wherever you need to go and then stay there for a while,” says Hardeman. “So we are perpetuating a cycle of disadvantage for people who already are very disadvantaged in our communities.”

Abortion bans can also lead to disruption of care because health-care providers, including physicians and pharmacists, may fear criminal prosecution if they provide abortion-related services.

“Anytime you have disruptions in care, Black and brown people are the ones who suffer the most,” says Gillispie-Bell, who is also medical director for Louisiana’s Maternal Mortality Review Committee and Perinatal Quality Collaborative.

Explain to your audiences that maternal mortality can affect anyone: “I think that people still think that this is a problem among poor people or poor Black people or uneducated, poor Black people,” says Gillispie-Bell. “And then they feel like ‘Well, that makes sense that they would have worse outcomes.’”

But as stories have documented in recent years, Black women with resources, including professional tennis player Serena Williams, can also be at risk of developing serious complications, which can be deadly if they’re dismissed by medical professionals.

“[Willliams] was begging for somebody to listen because she was having a blood clot in her lungs,” adds Gillispie-Bell.

Explain to your audiences how racism is one of the main drivers of health disparities today. And have conversations with scholars who are from the communities that are most impacted by these issues, says Hardeman. Seek diverse sources.

And while highlighting disparities in maternal health, also point out solutions and improvements, says Gillispie-Bell.

“The reason I say that is because while we want everybody to be aware [of disparities], we need to highlight [improvements], because we are finding out patients are just extremely fearful of going into the health-care system,” she says. Highlight local efforts and improvements and let audiences know what they can do to help improve outcomes.

Differences in definition of maternal mortality

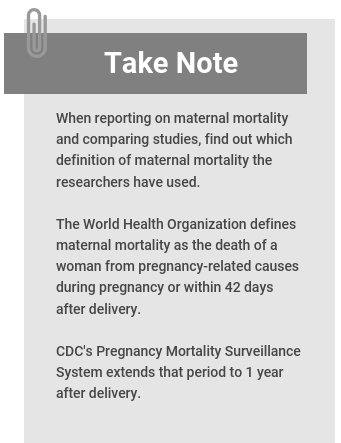

The World Health Organization defines maternal mortality as the death of a woman from pregnancy-related causes during pregnancy or within 42 days after the end of pregnancy.

The CDC’s Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System extends that period to 1 year from the end of pregnancy, while the agency’s National Center for Health Statistics, uses WHO’s definition.

Take note of the research studies’ definition of maternal mortality, especially when comparing data. In a 2020 article in ProPublica, Nina Martin explains the definition of maternal mortality that ends at 42 days leaves out many new mothers who die within a year after giving birth and may lead to underestimation of maternal mortality rates in the U.S.

A note on pregnancy terminology

There are currently no standards for an inclusive terminology for people who are pregnant and give birth.

The AP Stylebook says “pregnant women” is fine, and so is “pregnant people.”

The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, a nonprofit organization in the U.S. dedicated to improving maternal and child outcomes, advises health providers to use the gender pronouns preferred by the patient.

“When addressing or referring to a cohort of pregnant people for whom gender identity is known to be uniformly women, both ‘pregnant women’ and ‘pregnant people’ are accurate, though ‘pregnant women’ is more specific,” according to the society.

“When addressing or referring to pregnant people as a whole group, for whom gender identity is unknown and should not be assumed, the terms ‘pregnant people,’ ‘pregnant individuals,’ ‘birthing people,’ or ‘birthing individuals’ are most accurate, as they include cisgender women, transgender men, and nonbinary people who are capable of experiencing pregnancy,” it adds in a statement published in April 2022.

In the research roundup below, we use the language used by the researchers. The studies summarized below address topics such as news coverage of disparities in maternal mortality, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the potential impact of abortion bans. They are followed by additional reading recommendations and resources for journalists.

Research roundup

Historical and Recent Changes in Maternal Mortality Due to Hypertensive Disorders in the United States, 1979 to 2018

Cande V. Ananth; et al. Hypertension, Sept. 2021.

The study assesses how maternal age, year of death and year of birth contributed to hypertension-related maternal death trends in the United States from 1979 to 2018. There were 3,287 maternal deaths related to high blood pressure during those years. The women included in the study were between 15 to 49 years old. The study defines maternal mortality as death during pregnancy or within 42 days of pregnancy.

The findings: The hypertension-related maternal mortality rate among Black women was 5.4 per 100,000 live births. For white women the rate was 1.4. The overall rate was 2.1. Researchers also found being older was associated with an increased rate of hypertension-related maternal mortality. The rate was highest among women 45 to 49 years old. They also found an association between obesity rates and hypertension-related maternal mortality.

Key takeaway: “The study critically underscores the need (1) to develop targeted prenatal interventions, including tight blood pressure control and efforts to reduce body mass index, to ameliorate rates of hypertensive conditions before and during pregnancy and (2) to address the prevailing and concerning race disparity in maternal deaths with hypertension as the cause,” the researchers write.

A related study: “Treatment for Mild Chronic Hypertension during Pregnancy,” by Alan Tita; et al., published in the New England Journal of Medicine in May 2022, finds that controlling blood pressure of pregnant women with mild chronic hypertension leads to better pregnancy outcomes. Also, see this list of solutions from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

All-Cause Maternal Mortality in the U.S. Before vs. During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Marie Thoma and Eugene Declercq. JAMA Network Open, June 2022.

The study examines the role of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 maternal death rates in the U.S. after the National Center for Health Statistics reported the maternal mortality rate increased 18.4% between 2019 and 2020. Researchers used NCHS data from 2018 to 2020. The study defines maternal mortality as death during pregnancy or within 42 days of pregnancy.

The findings: In 2018 and 2019, 1,588 maternal deaths occurred, a rate of 18.8 per 100,000 live births. The number of maternal deaths during the pandemic, in 2020, was 684, or a rate of 25.1 per 100,000. That’s a relative increase of 33.3%. Absolute and relative changes from before and during pandemic were highest for Hispanic and Black women. COVID-19 was listed as secondary cause of death in 15% of maternal deaths in the second, third and fourth quarter of 2020. This percentage was highest for Hispanic women (32%) and Black women (13%), compared with white women (7.3%), the authors report.

Key takeaway: “Change in maternal deaths during the pandemic may involve conditions directly related to COVID-19 (respiratory or viral infection) or conditions exacerbated by COVID-19 or other health care disruptions (diabetes or cardiovascular disease), but could not be discerned from the data,” researchers write. “Future studies of maternal death should examine the contribution of the pandemic to racial and ethnic disparities and should identify specific causes of maternal deaths overall and associated with COVID-19.”

The Pregnancy-Related Mortality Impact of a Total Abortion Ban in the United States: A Research Note on Increased Deaths Due to Remaining Pregnant

Amanda Jean Stevenson. Demography, December 2021.

The research note estimates the increase in pregnancy-related deaths that would occur because of a higher risk of death from continuing a pregnancy rather than being able to have a legal abortion. The author uses CDC data from 2017.

The findings: If there were a total ban on abortion in the U.S., the estimated number of pregnancy-related deaths would increase by 7% from 675 to 724 in the first year. In following years, the number would increase to 815, a 21% increase. Black people would experience the greatest increase in deaths, at 33% after the first year of a hypothetical total abortion ban across the country.

Key takeaway: “Any state-level total or nearly total ban on abortion could also cause more pregnancy-related deaths … if pregnant people do not successfully access abortion via self-management or travel to another state,” Stevenson writes. “Similarly, other abortion bans (e.g., banning abortions sought for specific reasons or at specific gestations) will also cause more deaths if they lead to more pregnancies being continued.”

Preventing Pregnancy-Related Mental Health Deaths: Insights From 14 U.S. Maternal Mortality Review Committees, 2008-17

Susanna Trost; et al. Health Affairs, October 2021.

The study looks at pregnancy-related deaths due to mental health conditions, including substance use disorders and suicides, based on data from 14 state Maternal Mortality Review Committees between 2008 and 2017. The committees define maternal mortality as death during pregnancy or within one year after pregnancy.

The findings: Among 421 pregnancy-related deaths, 11% were due to mental health conditions. All the pregnancy-related mental health deaths in this study were determined by Maternal Mortality Review Committees to be preventable. Most deaths occurred 36 to 43 days after delivery. In total, 63% of pregnancy-related mental health deaths were by suicide. They were more likely to occur among white people (86%), compared with 2% among Black people. The authors note that the observed racial and ethnic disparities may reflect actual differences in leading causes of death, and differences in screening and identification practices. “For example, White people are more likely to be screened for depression at delivery than Black people,” they write.

Key takeaway: “Our findings show that maternal health cannot be promoted without addressing maternal mental health,” the authors write. “As evidenced by MMRC recommendations, there are many opportunities for preventing pregnancy-related mental health deaths through improvements in coordination of care; access to and availability of naloxone; access to treatment and services for SUD and other mental health conditions; prescribing practices; screenings and assessments; social, family, and peer support; and education for patients, providers, and the public.”

Related: “Pregnancy-Related Deaths: Data from 14 U.S. Maternal Mortality Review Committees, 2008-2017,” by Nicole Davis, Ashley Smoots and David Goodman, published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2019, summarizes data from 14 Maternal Mortality Review Committees in the U.S. between 2008 and 2017 to identify trends.

State Abortion Policies and Maternal Death in the United States, 2015‒2018

Dovile Vilda; et al. American Journal of Public Health, May 2021.

The study aims to examine the association between variations in state-level abortion restriction policies in 2015 and maternal mortality rates from 2015 to 2018 in the U.S.

The findings: States that had more abortion restriction policies in place had a 7% increase in maternal mortality compared with states that had fewer restrictions. Abortion-restricting laws may contribute to maternal death directly and indirectly, the authors explain. Abortion restrictions can lead to more unsafe and illegal abortions. They can also put the lives of pregnant women with chronic health conditions at risk, who are forced to carry an unwanted pregnancy to term.

Key takeaway: Restricting access to abortion care at the state level may increase the risk for maternal mortality, the authors write. “Our findings suggest the cumulative impact of abortion restrictions on maternal death, adding to a limited body of empirical studies linking rising maternal mortality and reduced access to reproductive health services in the United States,” they write.

Black Maternal Mortality in the Media: How Journalists Cover a Deadly Racial Disparity

Denetra Walker and Kelli Boling. Journalism, January 2022.

The study is based on interviews with four women journalists who specialize in women’s issues and health and explores how they cover Black maternal mortality. The reporters were Sarah Fentem, a white health reporter who covers medical news for St. Louis Public Radio, an NPR affiliate; Rochaun Meadows-Fernandez, a Black health journalist who writes cultural pieces about Black health; Dr. Cynthia Greenlee, a Black woman who works as a senior editor for an online reproductive health publication; and Nina Martin, a Latina, who worked for ProPublica at the time, covering gender and sexuality issues.

The findings: “Women journalists in this study aimed to be objective and not take a position as advocates, while balancing their work to frame this topic as a public health issue,” the authors write. “By purposefully centering Black women, doctors, and families in stories as sources, the journalists elevated their voices in a broader, societal view to shed light on the experiences of Black women.”

Key takeaway: “The practice of using the voices of marginalized groups to tell their story is an important lesson,” researchers write. “The journalists were clear they were not taking a hard stance on their position as advocates; however, they did feel as if elevating the stories of Black women helped frame this topic as important.”

More studies of note

- “Black maternal mortality in the media: How journalists cover a deadly racial disparity,” by Denetra Walker and Kelli Boling, published in Journalism in January 2022, is based on interviews with four women journalists and finds: “The practice of using the voices of marginalized groups to tell their story is an important lesson. The journalists were clear they were not taking a hard stance on their position as advocates; however, they did feel as if elevating the stories of Black women helped frame this topic as important.”

- “Pregnancy-Related Deaths: Data from Maternal Mortality Review Committees in 36 U.S. States, 2017–2019,” by Susanna Trost; et al., published in September 2022 by the CDC, finds that 80% of pregnancy-related deaths in the U.S. are preventable and that the leading cause of pregnancy-related death varies by race and ethnicity. During the study period, 22% of deaths occurred during pregnancy, 25% occurred on the day of delivery or within 7 days after, and 53% occurred between 7 days to 1 year after pregnancy, the report finds.

- “Abortion Access as a Racial Justice Issue,” by Katy Backes Kozhimannil, Asha Hassan, and Rachel R. Hardeman, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in September 2022, is a perspective article in which the authors say, “Abortion access is a racial justice issue, and it is today’s civil rights battle worthy of tenacious engagement by professionals in medicine, policy, and public health.”

- “Structural Racism and Maternal Health Among Black Women,” by Jamila K. Taylor, published in the Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics in January 2021, provides a historical overview of racism in American, including the study of obstetrics and gynecology using enslaved Black women in the 1800s, and describes the path to today’s racial inequalities in health care and poor maternal health among Black women.

- “Maternal Mortality in the United States: A Review of Contemporary Data and Their Limitations,” by Dr. Andreea Creanga, published in Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology in June 2018, provides an overview of maternal mortality data and their limitations in the United States. “Of about 16.1 million induced abortions performed in the United States during 1998 to 2010, 108 women died from abortion-related complications for a mortality ratio of 0.7 deaths per 100,000 induced abortion procedures,” Creanga writes.

- “The Impact of Racism on Maternal Health Outcomes for Black Women,” by Gabrielle T. Wynn, published in University of Miami Race & Social Justice Law Review in December 2019, is a 25-page Juris Doctor dissertation that explores the role of racism on maternal health disparities and offers solutions.

- “U.S. Maternal Mortality Within a Global Context: Historical Trends, Current State, and Future Directions,” by Regine Douthard, et al., provides a perspective on maternal mortality trends in the U.S. and evaluates it in a global context.

- “Healthcare Utilization and Maternal and Child Mortality During the COVID-19 Pandemic in 18 Low- and Middle-Income Countries: An Interrupted Time-Series Analysis with Mathematical Modeling of Administrative Data,” by Tashrik Ahmed; et al., published in PLOS Medicine in August 2022, finds that reduced use of health-care services during the COVID-19 pandemic threatens to reverse global gains in reducing maternal and child mortality.

- “Developing Tools to Report Racism in Maternal Health for the CDC Maternal Mortality Review Information Application (MMRIA): Findings from the MMRIA Racism & Discrimination Working Group,” by Rachel Hardeman; et al., published in Maternal and Child Health Journal, January 2022, describes the results from a working group selected by the CDC Foundation in partnership with maternal health experts, to develop a definition of racism that can be used on the Maternal Mortality Review Information Application form, which is used by Maternal Mortality Review Committees.

- “Maternal Mortality: Trends in Pregnancy-Related Deaths and Federal Efforts to Reduce Them,” by the U.S. Government Accountability Office, published in March 2020, describes the Health and Human Services’ ongoing efforts to prevent pregnancy-related deaths.

- “A Call to Action: Cardiovascular-Related Maternal Mortality: Inequities in Black, Indigenous, and Persons of Color,” by Erin Ferranti; et al., published in the Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing in July 2021, calls for a “focus on comprehensive and systemic approaches that address the social and structural issues underlying maternal health inequities.”

- “Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Health: An Overview,” by Samantha Artiga, Olivia Pham, Kendal Orgera and Usha Ranji, published by the Kaiser Family Foundation in November 2020, provides an overview of disparities in maternal and infant health in the U.S.

- “Maternal Mortality in the United States: A Primer,” by Eugene Declercq and Laurie Zephyrin, published by The Commonwealth Fund in December 2020, provides an overview of maternal mortality and related data in the U.S.

- “Maternal Mortality Measurement: Guidance to Improve National Reporting,” by the United National Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group, published by the World Health Organization in July 2022, outlines best practices for data collection and interpretation.

Additional reading

- “Lost Mothers: Maternal Care and Preventable Deaths,” by Nina Martin; et al., published in ProPublica in 2017, is a series about maternal mortality in the United States.

- “When the Water Breaks,” by Layla A. Jones, published in The Philadelphia Inquirer in July 2022, traces America’s maternal mortality crisis back to Philadelphia and America’s first delivery wards and the persisting racial disparities today.

- “Stark Disparities Persist in Missouri’s Maternal Mortality Rate, State Board Finds,” by Tessa Weinberg, published in the Missouri Independent in August 2022, is about a multi-year report that analyzes Missouri’s maternal mortality trends.

- “Postpartum Care Falls Short for Black Women. One Mother is Trying to Fix That,” by Juana Summers, Michael Levitt and Sarah Handel, published on National Public Radio’s All Things Considered in August 2022, is about She Matters, a digital platform focused on disparities in postpartum care for Black mothers.

- “New Alabama Maternal Mortality Report Highlights Preventable Deaths, Substance Abuse,” by Sarah Swetlik, published on AL.com in August 2022, explains the findings of Alabama’s Maternal Mortality Review Committee’s latest report.

- “Raising The Stakes To Advance Equity In Black Maternal Health,” by Michele Cohen Marill, published in Health Affairs in March 2022, is about Penn Medicine tying executive compensation to the goal of reducing complications from giving birth.

- “Getting To The Heart Of America’s Maternal Mortality Crisis,” by Michele Cohen Marill, published in Health Affairs in December 2021, is about a cardio-obstetrics program in a Missouri hospital and a national registry that targets the leading causes of maternal death.

More resources for journalists

- “Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2020,” by Donna Hoyert, published in CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics’ E-Stats in February 2022, provides the latest maternal mortality data in the United States.

- March of Dimes, a U.S. nonprofit organization that focuses on improving health of mothers and babies, has accessible information and annual reports on maternal and infant health in the U.S. Here’s the organization’s information page on maternal deaths.

- The Guttmacher Institute is a research and policy organization focused on sexual and reproductive health rights around the world.

- Black Mamas Matter Alliance is a nonprofit group that advocates for Black maternal and reproductive health. Here’s a list of other organizations advocating for Black mothers.

- Center for Reproductive Rights is a global human rights organization of lawyers and advocates of reproductive rights.

- Perinatal Quality Collaboratives are state or multistate networks of teams that focus on improving the quality of care for mothers and babies. Here’s a list by state.

- Maternal Mortality Review Committees are multidisciplinary committees in states and cities that perform comprehensive reviews of deaths among women within a year of the end of pregnancy. Here’s a list by state.

- Every Mother Counts is a nonprofit organization working to make pregnancy and childbirth safe for mothers around the world. It was founded by American model and humanitarian Christy Turlington Burns after experiencing her own childbirth complications.

- “Eliminating Preventable Maternal Mortality and Morbidity,” is The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ policy statement on combating maternal mortality.

Free multimedia collections for news stories

- CDC’s Public Health Image Library (PHIL) has some photo and illustration options. You can also download and use charts and graphs from CDC reports, including Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

- SciLine offers video interviews with experts, which journalists can download and use for free.

Expert Commentary