The relationship between gun ownership and safety is a hotly debated one in the United States, yet it has also been the subject of extensive data-driven analysis. A 2014 meta-analysis in the Annals of Internal Medicine found that people who have access to firearms at home are twice as likely to die in gun-related homicides and more than three times as likely to commit suicide than those without such access. The study also found that men with access to a gun at home were nearly four times more likely than women to commit suicide with a gun, while women were three times more likely to die in a gun-related homicide.

In addition to the question of home firearms, considerable debate surrounds the impact of state laws allowing or prohibiting U.S. residents to carry weapons in public, either in the open or concealed. Firearms advocates often assert that such right-to-carry (RTC) laws have a major role in reducing crime. A 1997 working paper by John R. Lott Jr. and David B. Mustard of the University of Chicago provided support for this theory, but its findings were disputed by a 2003 study from Ian Ayres and John J. Donohue of Yale and Stanford, respectively. Their study was itself subject to a critical review, to which they replied.

A 2004 meeting by National Research Council — the preeminent research body in the United States, part of the National Academy of Sciences and chartered by Congress — examined the question, and an associated report from a research committee of experts, “Firearms and Violence: A Critical Review,” concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support claims about right-to-carry laws and crime:

[A]nswers to some of the most pressing questions cannot be addressed with existing data and research methods, however well designed. For example, despite a large body of research, the committee found no credible evidence that the passage of right-to-carry laws decreases or increases violent crime, and there is almost no empirical evidence that the more than 80 prevention programs focused on gun-related violence have had any effect on children’s behavior, knowledge, attitudes, or beliefs about firearms. The committee found that the data available on these questions are too weak to support unambiguous conclusions or strong policy statements.

A member of the committee, political scientist James Q. Wilson, then at Pepperdine, agreed with the report’s overall conclusions, but in a dissent wrote that the evidence “suggests that RTC laws do in fact help drive down the murder rate.” This dissent was challenged by the National Research Council, which stated that “the scientific evidence does not support” Wilson’s position.

A 2014 study for the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) by John J. Donohue, Abhay Aneja and Alexandria Zhang, “The Impact of Right-to-Carry Laws and the NRC Report: The Latest Lessons for the Empirical Evaluation of Law and Policy,” revisits these much-cited studies, seeking to gain better insight into the relationship between RTC laws and violent crime.

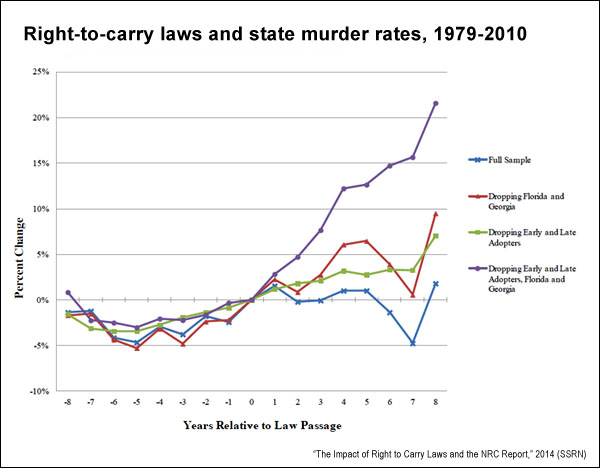

The researchers, based at Stanford and Johns Hopkins, expand on the original data by adding a decade of county-level observations, analyzing state panel data for the period 1979-2010. They also control for potentially confounding variables over the study period, including the level of police staffing, incarceration rates and the crack epidemic in the late 1980s and early 1990s — for example, Florida experienced enormous drops in murder during the 1990s that may have been completely unrelated to its passage of a right-to-carry law. Finally, while the original Lott-Mustard study used 36 “highly collinear” demographic variables, the new study uses six controls that the authors assert are more relevant to the question at hand.

The NBER study’s findings include:

- Right-to-carry laws were found to be associated with higher rates of murder, rape, aggravated assault, robbery, auto theft, burglary and larceny.

- In each of seven crime categories, at least one of the four estimates used by the authors suggests that RTC laws increase crime at the 0.10 level of significance, with murder, rape and larceny estimates reaching significance at the 0.05 level.

- Eleven of 28 estimates suggest that RTC laws increase aggravated assault 8%, and the authors note these results may actually be understated: “Our analysis of admittedly imperfect gun-aggravated assaults provides suggestive evidence that RTC laws may be associated with large increases in this crime, perhaps increasing such gun assaults by almost 33%.”

- Rising crime rates were observed prior to the passage of RTC laws, and these in turn would “likely lead to a bias in favor of finding a deterrent effect.” However, excluding early and late adopters as well as Georgia and Florida, both of which were outliers, rates of murder and other violent crimes continued to rise strongly after the passage of RTC laws.

- The 36 demographic variables used in the 1997 working paper were “the most important driver of the ostensible decline in crime from RTC laws.” The new research, quoting the 2003 Ayres and Donohue study, confirms that “the results are incredibly sensitive to the inclusion of various seemingly unimportant demographic controls,” even with the addition of 10 more years of data. Only by using six relevant controls rather than the 36 original variables were the impacts of RTC laws on violence fully evident.

- The report corrects several standard errors in the Lott-Mustard and National Research Council data that produced the results that laid the groundwork for Wilson’s dissent. “With correct standard errors, none of the estimates that Wilson thought established a benign effect of RTC laws on murder would have been statistically significant. Thus, getting the standard errors right might have kept Wilson from writing his misguided dissent to the benefit of Wilson, the [National Research Council] majority and the public.”

In addition to the findings related to the relationship between RTC laws and violent crime, the authors note that there are several lessons here for researchers: One is how easy it is for data errors to slip into empirical studies, and that the peer-review process is not well-equipped to detect such errors. In addition, “best practices” in econometrics are not fixed, but constantly evolving: “Researchers and policymakers should keep an open mind about controversial policy topics in light of new and better empirical evidence or methodologies.”

Related research

An April 2015 study in Behavioral Sciences and the Law, “Guns, Impulsive Angry Behavior and Mental Disorders: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication,” examines the likelihood that adults with self-reported anger-management or mental-health issues to possess or carry guns. The study, authored by researchers at Harvard, Columbia and Duke universities, “found that a large number of individuals in the United States self-report patterns of impulsive angry behavior and also possess firearms at home (8.9%) or carry guns outside the home (1.5%). These data document associations of numerous common mental disorders and combinations of angry behavior with gun access. Because only a small proportion of persons with this risky combination have ever been involuntarily hospitalized for a mental health problem, most will not be subject to existing mental health-related legal restrictions on firearms resulting from a history of involuntary commitment.”

Also of interest is a 2012 meta-analysis by researchers from Arizona State and the University of Cincinnati, “The Effectiveness of Policies and Programs That Attempt to Reduce Firearm Violence,” examined 29 rigorous studies on laws and programs to reduce gun violence. It found that probation strategies — increased contact with police, probation officers and social workers — were the most effective, while “prosecutorial strategies” — harsher sentences and restricted bail opportunities — showed the least promise.

Keywords: crime, law, guns, sex crimes, mental health

Expert Commentary