Josh Neufeld is a cartoonist and journalist whose comics have covered a wide range of topics, including public health crises, academic research and journalism itself. He is best known for his book A.D.: New Orleans After the Deluge, which tells the true story of several New Orleans residents who lived through Hurricane Katrina. He is also the co-author of The Influencing Machine: Brooke Gladstone on the Media, an illustrated history of journalism and numerous other works — including a comics journalism piece about social science research on consumer behavior.

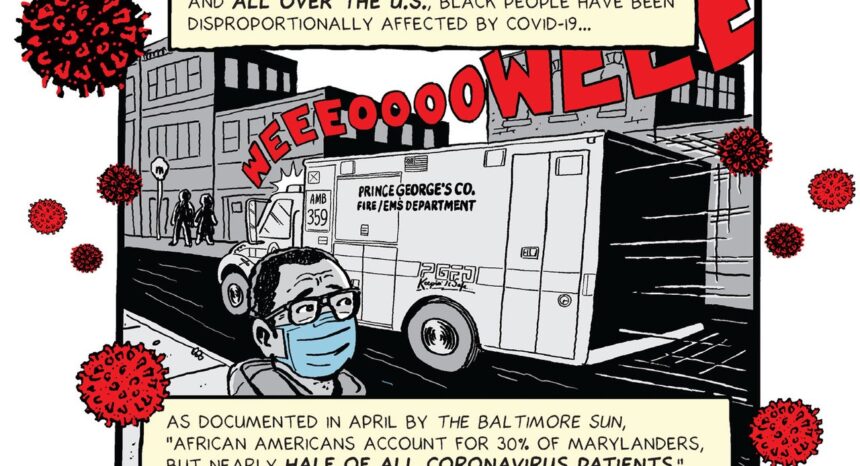

Neufeld authored our new feature, “A Tale of Two Pandemics: Historical Insights on Persistent Racial Disparities,” which uses the form of comics journalism to highlight a recent research article published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

In that article, medical doctors Lakshmi Krishnan, S. Michelle Ogunwole and Lisa A. Cooper discuss racial health disparities during the 1918 influenza pandemic, with an eye toward the future. Their research, the doctors explain, “reveals that critical structural inequities and health care gaps have historically contributed to and continue to compound disparate health outcomes among communities of color” and “frames a discussion of racial health disparities through a resilience approach rather than a deficit approach and offers a blueprint for approaching the COVID-19 crisis and its afterlives through the lens of health equity.”

“A Tale of Two Pandemics” draws on the research article itself as well as interviews with Krishnan, Ogunwole and Cooper, in which they elaborate on the disturbing parallels between the spread of misinformation during both the 1918 and COVID-19 pandemics. The doctors are the main characters in the comic, and their speech-bubble quotes come directly from the interviews. (In cases where Neufeld is quoting directly from their research article, he depicts the authors speaking in unison — akin to a Greek chorus.)

“I let their voices guide the narrative,” Neufeld says. “I’m so grateful that they spoke to me about their article!”

Via an e-mail interview, Journalist’s Resource asked Neufeld to discuss the benefits, challenges and processes of practicing comics journalism. This Q&A has been lightly edited for space and clarity.

Journalist’s Resource: For starters, what is comics journalism?

Josh Neufeld: True to its name, it’s journalism using the comics form. As a comics journalist, I research, report, and tell true-life stories — but with the added component of pictures, word balloons, and captions. The characters I portray are real people, and the text in their word balloons are actual quotes from my interviews with them.

JR: What can comics journalism do that other forms of journalism cannot? What are its limitations?

Neufeld: At its best, comics journalism brings the reader into the story in an immersive way that other mediums can’t compete with. A comics story has a certain immediacy — it feels like it’s happening right now, rather than retrospectively — and comics engender a strong sense of empathy for the “characters” in the stories. Stories featuring compelling characters in fraught situations are particularly powerful when told in comics form.

Comics embody a unique alchemy of words and pictures, so the form can also be effective in breaking down complex concepts into their component parts, or bringing life to dry charts and statistics.

Explanatory stories, for instance, work well when they can incorporate quotes from real people who can connect with the reader. But stories that require a lot of exposition, and move quickly from scene to scene, don’t work so well as comics. In my opinion, comics journalism stories are most effective when they are told “in-scene” with people talking, as opposed to using a lot of explanatory captions. But the most creative comics journalists are able to make any kind of story work in comics form!

Also, since most comics journalism stories require a lot of time to produce, they’re not really ideal for breaking news or daily reporting. I usually think of even my shorter pieces as a type of long-form journalism.

JR: Do you draw in the course of reporting, or do you wait until the interviews/research are finished before you start drawing? What are some of the visual strategies you use to achieve journalistic authenticity in your work?

Neufeld: My typical reporting process starts with preliminary research (including visual research) and then interviews with the subjects.

With interviews/reporting, some artists do in-person sketching, but I tend to focus on taking lots and lots of photographs — not only of my subjects, but of their homes, their pets, the neighborhood and so on — anything I think I might need to draw afterward. I often will draw detailed floor plans of important interiors, so that when I draw a scene I’ll always know what furniture and “props” are in the background of that panel.

After compiling this material, I think about the most effective presentation for the story, in terms of its narrative structure and the most punchy visual components. I usually also draw some sketch “turnarounds” of my main characters — views of them from the front, side and back, to get a sense of how they will look and interact with the environment.

I then write a full script, formatted in a similar manner to a screenplay. I describe what will be visually represented in each panel and what captions or word balloons will be included. I try to create a dynamic narrative, one that has the feel of, say, an exciting television show or movie.

One of the freedoms that the form allows is that the reader accepts that some amount of creative license will be employed — obviously, as the storyteller, I wasn’t there when the character I interviewed survived the flooding of their city or was attacked by the police during a peaceful demonstration. And even if I have photographic or video reference from an event, I’m still “making up” details or background characters to fill out a scene.

But in my scripts, I always stick to the facts as I have gleaned them from interviews, data and other reporting.

After the script is written and approved by my editor, I lay out the story, dropping in the text where necessary so my editor can read through the piece and sign off it. At that point, I start drawing, continually referring to photo reference and details I got from talking to my subjects/witnesses. Once the penciling is done, the editor once again signs off before I move to the final inking and coloring stage.

It’s a laborious process, with a lot of check-ins along the way, but I don’t mind because my primary goal is to serve the truth of the people whose story I am telling.

JR: What are some of the biggest challenges and toughest choices you have to make when creating any given comic?

Neufeld: Comics are an incredibly pithy form — long-winded quotations and lots of explanatory text make a tiresome reading experience. So when it comes to quotes and narration, I’m always cutting, cutting, cutting, trying to find that perfect image choice (or facial expression) that can carry the bulk of the narrative weight. Like any other form of writing, in the initial drafts there’s always a lot of “killing your darlings” — cutting great quotes and the like because they just don’t fit or would distract from the through-line of the story.

Tone is also really important to a piece of comics journalism (especially because of the hurdle of “believability” I mention later). So even though humor and exaggeration are powerful tools of comics, I sometimes have to restrain my impulse in that direction if I (or my editor) feels it would take away from the story’s authenticity. I still try to use those tools, but probably in more moderation than I would in a fiction piece.

JR: What are some common misconceptions/misperceptions about comics journalism?

Neufeld: One of the biggest hurdles comics journalism stories face is the entrenched expectation that all comics stories are fictional. Historically, the comics produced in our country have mostly centered on humor, adventure and superheroes, so it’s still a struggle to convince your average reader that a nonfiction story told in comics form is “legitimate.” Thank goodness for the work of creators like Will Eisner, Harvey Pekar, Art Spiegelman, Chris Ware, Alison Bechdel and Marjane Satrapi who have elevated the perception of the comics form in recent decades!

The other perception that comics journalism struggles against is subjectivity. People often think that because the work is drawn, it is more subjective than other forms of journalism. But of course subjectivity comes into play in all other journalistic media, from the video and audio edits made in TV and radio studios to the various edits and omissions made to events and quotes in print stories. Comics journalism is just more obvious about it, which makes it easier to target!

That’s why I always try to be as transparent as possible when I discuss my work: showing photos of the people I interviewed and places I am depicting, talking about my process and freely admitting to places in the narrative where I used creative license.

JR: For those who want to learn more about the genre — and to read more of it, could you please suggest some further reading?

Neufeld: My introduction to the form came by way of Maltese-American cartoonist Joe Sacco, who is known for his long-form narratives about areas of conflict in the Middle East and the former Yugoslavia. Books to look for of his include Palestine and Safe Area Gorazde, among many others. Sacco is a rigorous journalist and an incredible draftsman. He popularized the form and to me is still the standard-bearer.

Comics journalist Dan Archer created a wonderful two-pager on comics journalism for Poynter [Institute] some years back. It goes over the history of the form (dating back to the 19th century), mentions some creators and discusses the methods (as well as those who criticize the form).

The Nib is a great site for current works of comics journalism and is updated almost every day. They make a point of featuring female cartoonists and work by people of color and there’s always a new, incredible piece of comics journalism on the site. (They also publish sharp-edged political and editorial cartoons.) A few times a year, The Nib publishes a print edition of comics on a particular theme.

Two European English-language sites, both published out of the Netherlands, also feature comics journalism: Drawing The Times and Cartoon Movement.

And, of course, my own website has a large collection of comics journalism pieces I have done over the years.

Expert Commentary