The estimated number of people with dementia is expected to increase to 153 million by 2050 worldwide, compared with an estimated 57 million cases in 2019, according to recent projections published in The Lancet Public Health.

In the U.S., dementia cases are expected to double to 10.5 million by 2050, up from 5.3 million in 2019, shows “Estimation of the Global Prevalence of Dementia in 2019 and Forecasted Prevalence in 2050: An Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.”

The study, published in January, adds to the body of evidence that dementia will continue to be among the leading causes of death and disease worldwide, unless effective treatments enter the market and nations begin to address some of the common risk factors for dementia, including obesity, diabetes and smoking.

Dementia is not a specific disease. It’s a general term that refers to a collection of symptoms such as memory loss, cognitive impairment and personality changes that interfere with daily life.

The symptoms are caused by disease processes that lead to the death of brain cells. Researchers have been trying to find out how to stop or prevent that from happening.

There are several common forms of dementia:

- Alzheimer’s disease, the most common dementia diagnosis among older adults, makes up as many as 70% of all dementia cases around the world.

- Frontotemporal dementia is rare and mostly happens in people younger than 60.

- Lewy body dementia is caused by abnormal deposits of a protein called alpha-synuclein.

- Vascular dementia is caused by conditions that damage blood vessels in the brain.

- It is also common for older adults with dementia to have more than one form of dementia. This is called mixed dementia.

Alzheimer’s disease and dementia are not interchangeable terms. You can, however, say ‘Alzheimer’s disease and all other dementia,’ according to Liz McCarthy, health systems director and research champion at the Alzheimer’s Association, one of the largest nonprofit funders of Alzheimer’s research in the world.

Dementia is not a normal part of aging, although it is most commonly diagnosed among older adults. Nearly 10 million new cases of dementia are diagnosed around the world each year, according to the World Health Organization, making it the seventh leading cause of death.

In the United States, an estimated 6.2 million Americans 65 years and older lived with Alzheimer’s disease in 2021. Of those, 72% percent were 75 years or older, according to latest data from the Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s disease is the seventh leading cause of death in the U.S., according to the CDC.

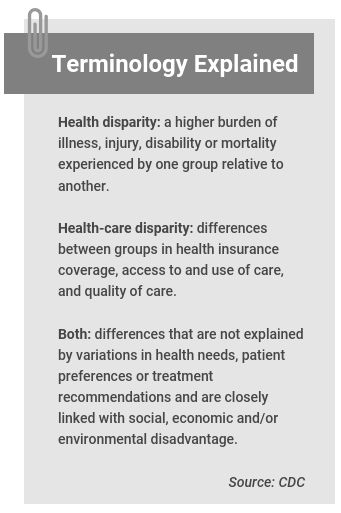

Older African Americans and Hispanics are disproportionately more likely than whites to have Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias. According to some estimates 18.6% of African Americans and 14% of Hispanics 65 years and older have Alzheimer’s disease compared with 10% of whites. For reasons yet unknown, the rate of dementia is also higher in women than in men across races and ethnicities.

Pinning down the numbers for different forms of dementia is difficult, because to get the most accurate diagnosis, patients need to have a brain scan and that technology is costly and not available to everyone. So, many people are diagnosed based on their symptoms. If their doctor lacks expertise in dementia diagnosis, a patient might just receive an Alzheimer’s diagnosis by default, says McCarthy.

Meanwhile, research has shown that dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, is underdiagnosed.

“Only about 50% of the people with Alzheimer’s disease are diagnosed,” says McCarthy.

There are currently no drugs that reverse dementia. Aduhelm, which was approved in June 2021 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, is the first new treatment approved for Alzheimer’s since 2003. It targets beta-amyloid plaques, which can kill brain cells and are a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. However, there are still questions about whether the treatment actually slows memory loss. The drug has also been controversial in terms of cost, safety and the accelerated process through which it was approved. (For a detailed explanation of the controversy surrounding Aduhelm, see our explainer on the FDA’s accelerated approval process.)

In addition to the search for an effective drug, a few areas are currently of special interest to scientists.

One area, which is new, is the connection between the COVID-19 infection and long-lasting or permanent damage to the brain. For now, preliminary studies hint at a potential link between coronavirus infection and “brain fog.”

Researchers also continue to make progress in finding biomarkers in the blood that can signal changes in the brain, similar to how diabetes is diagnosed with blood tests.

A third area of interest is prevention, with a focus on risk factors such as types of diet, level of exercise, impact of social engagement and chronic diseases like diabetes.

“So just taking care of your brain from the very get-go is going to put you in a better position as you age,” says McCarthy.

Researchers are also looking at barriers in accessing care and how societal and structural disparities, such as exposure to stress, air pollution and racism can increase a person’s risk of developing dementia.

Below, we’ve gathered several reports and studies that can help journalists add context and data to their stories.

Estimation of the Global Prevalence of Dementia in 2019 and Forecasted Prevalence in 2050: An Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019

Global Burden of Disease 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. The Lancet Public Health, January 2022.

The study is part of the 2019 Global Burden of Disease Study, which is a worldwide observational epidemiological study led by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington. The GBD study has been examining various health trends regularly since 1990, with data from 204 countries and territories, 369 diseases and injuries and 87 risk factors. In their most recent analysis, researchers forecast the prevalence of dementia, including the role of three risk factors — obesity, diabetes and smoking. They leveraged country-specific estimates of dementia prevalence from the 2019 GBD study to project dementia prevalence globally, by world region and at the country level by 2050.

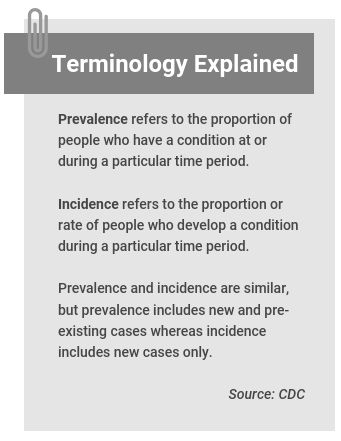

What they find: The team estimates that globally, the number of people with dementia will increase from 57.4 million in 2019 to 152.8 million in 2050. It’s important to note that the age- and sex-specific prevalence of dementia are projected to remain stable between 2019 to 2050, but the overall prevalence of dementia is expected to increase. (The world population is expected to increase by 2 billion in the next 30 years, from 7.7 billion in 2019 to 9.7 billion in 2050, according to a United Nations report.)

Other study findings include:

- Women are 1.7 times more likely to develop dementia than men and that pattern is expected to continue in the coming decades.

- There are geographic variations. The smallest percentage change in projected dementia cases is in high-income Asia Pacific countries (Brunei, Japan, South Korea and Singapore) and Western Europe. The largest in North Africa and the Middle East, and eastern sub-Saharan Africa.

Population growth and aging are the two leading attributors to increases in dementia cases, although, the importance of each factor varies by world region. Population growth contributed most to the increase in dementia cases in sub-Saharan Africa while aging contributed most to increases in East Asia.

What the authors write: “Growth in the number of individuals living with dementia underscores the need for public health planning efforts and policy to address the needs of this group,” they write. “Given that there are currently no available disease-modifying therapies, appropriate emphasis should be placed on efforts to address known modifiable risk factors.” They add that countries need to address structural inequalities to make a meaningful change in dementia rates.

They also point out large gaps “in the availability of quality end-of-life care for individuals with dementia,” adding that “such care can positively affect both individuals with dementia and their caregivers,” and call for evidence-based interventions to support caregivers.

The study was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Gates Ventures.

Race, Ethnicity and Alzheimer’s in America

Alzheimer’s Association, March 2021.

This special report accompanies the Alzheimer’s Association’s 2021 Facts and Figures report and is a first for the association. It examines perspectives and experiences of Asian, Black, Hispanic, Native and white Americans about Alzheimer’s and dementia care. The results are based on online surveys of 2,491 U.S. adults and 1,392 current or recent caregivers of adults 50 years and older with cognitive issues. The surveys were conducted between October and November 2020. They do not include people with dementia.

The surveys show that half of Black respondents who were not caregivers reported having experienced discrimination when seeking health care. The rate was 42% for Native Americans, 34% for Asian Americans and 33% for Hispanics. It also shows:

- 42% of Black caregivers were concerned that health providers don’t listen to what they’re saying because of their race, color or ethnicity. That’s compared with one-third of Native American, Asian American and Hispanic caregivers and 17% of white caregivers.

- 40% of those who cared for a Black person said race made it harder for them to get excellent health care. One in three caregivers of Hispanic individuals said the same.

- The majority of non-white Americans said it’s important for health providers to understand their ethnic or racial background and experiences.

- 62% of Black respondents believed medical research is biased against people of color. The group was also less interested in participating in clinical trials for Alzheimer’s than all other groups surveyed. When asked why, about 70% of the Black respondents selected “Don’t want to be a guinea pig” as the reason. In comparison, about half of white, Native American, Asian American and Hispanic respondents chose that option.

- Knowledge, concern and stigma about Alzheimer’s varies widely across racial and ethnic groups. For instance, Black, Hispanic and Native Americans were twice as likely as whites to say that they won’t see a doctor if they have memory problems. Also, 48% of white respondents said they were worried about developing Alzheimer’s, compared with 25% of Native Americans, 35% of Black respondents and 41% of Hispanics. More than half of non-white Americans believe significant loss of memory or cognitive abilities is “a normal part of aging.”

Key takeaway: “Overall, the results of the Alzheimer’s Association surveys indicate that despite ongoing efforts to address health and health care disparities in Alzheimer’s and other dementias, there is still much work to do,” according to the report. “The data suggest that discrimination and lack of diversity in the health care profession are significant barriers that demand attention.”

Population Estimate of People with Clinical Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment in the United States (2020–2060)

Kumar Rajan; et al. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, May 2021.

The study uses data from the Chicago Health and Aging Project, which enrolled participants 65 years and older in four Chicago neighborhoods from 1993 to 2012, with 10,342 participants over the project’s period. Using the data, researchers estimated the 2020 U.S. prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment (an early stage of memory loss). They then used the U.S. Census projections for population demographics from 2020 through 2060.

The findings: Prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease was 11.3% in the overall study population, 18.6% among Black participants, 14% among Hispanic participants and 10% among whites. The prevalence of mild cognitive impairment was 22.7% overall, 32% among Black participants, 25.9% among Hispanics and 21.1% among whites. The study also finds:

- An estimated 6.1 million older adults in the U.S. had Alzheimer’s disease in 2020. The number will increase to 7.2 million in 2025 and 13.9 million in 2060.

- By 2060, the proportions of Black and Hispanic people with Alzheimer’s are projected to increase to 24.5% and 26.8%, respectively, while it will decrease to 50.8% of whites.

- In 2020, 1.4 million more women had Alzheimer’s than men. This difference is projected to increase to 2.6 million in 2060. “Hence, the sex gap in the number of people with [Alzheimer’s] is expected to continue to widen in the United States over the next four decades,” the authors write.

- The number of people with early-stage memory loss in the United States is twice the number of people living with Alzheimer’s disease. The estimated 12.2 million people with early-stage memory loss due to all causes in 2020 is projected to increase to 21.6 million in 2060.

The takeaway: “The number of people with [Alzheimer’s disease] will increase as the “baby boom” generation reaches older ages, exerting a strong upward influence on disease burden,” the authors write.

Trends in Relative Incidence and Prevalence of Dementia across Non-Hispanic Black and White Individuals in the United States, 2000-2016

Melinda Power; et al. JAMA Neurology, March 2021.

The study investigates whether racial disparities in dementia prevalence and incidence changed in the U.S. between 2000 and 2016. It uses the Health and Retirement Study, a longitudinal study that surveys a representative sample of approximately 20,000 people 50 years and older in the U.S. Researchers focused on data from non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic Black participants 70 years and older.

Context: Studies have shown that Black people are almost twice as likely as whites to have dementia. These disparities are attributed to the cumulative effects of structural racism, which can affect brain health various mechanisms, the authors explain. The National Alzheimer’s Project Act was signed into law in January 2011 to create a national plan to increase research on Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. It also calls for decreasing disparities in minority populations at a higher risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

The findings: “There was no evidence to suggest either narrowing or widening of relative racial disparities in dementia prevalence or incidence,” the authors write. Black participants 70 years and older had an approximately 1.5 to 1.9 times higher prevalence of dementia compared with whites between 2000 and 2016.

The authors call for careful examination of how disparities in dementia risk arise and evolve “if we are to achieve the stated national goal of reducing or eliminating racial disparities in dementia prevalence.”

The study has an accompanying editorial by Carl Hill, the chief diversity, equity and inclusion officer for the Alzheimer’s Association. “Health equity can be achieved when all people have access to resources that help them to realize their full potential, despite socioeconomic position or socially determined circumstances,” he writes. “Identifying those who are most at risk is a critical first step for pursuing equity in dementia science.”

Additional reading

- 2021 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures, published in March 2021 by the Alzheimer’s Association, is a report on the public health impact of Alzheimer’s disease in the U.S., including incidence and prevalence, mortality and morbidity, use and costs of care, and the overall impact on caregivers and society. It also provides in-depth explanations of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

- Trends in US Medicare Decedents’ Diagnosis of Dementia From 2004 to 2017, published in JAMA Health Forum in April 2022, shows that the number of Medicare beneficiaries dying with a dementia diagnosis in the U.S. increased by 36% between 2004 and 2017. Some explanations for this increase could be increased awareness about dementia among patients and health care providers, as well as changes to billing practices, the authors write.

- Longitudinal Associations of Mental Disorders With Dementia; 30-Year Analysis of 1.7 Million New Zealand Citizens, published in JAMA Psychiatry in February 2022, finds “people with early-life mental disorders were at elevated risk of subsequent dementia and younger dementia onset.” Researchers write that their findings suggest that addressing mental disorders in early life might reduce risk of cognitive decline in later life.

- Global Prevalence of Young-Onset Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis, published in JAMA Neurology in July 2021, finds “an age-standardized prevalence of young-onset dementia of 119 per 100 000 population, although estimates of the prevalence in low-income countries and younger age ranges remain scarce. Young-onset dementia starts before age 65.

- Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care: 2020 Report of the Lancet Commission, published in The Lancet in July 2020, discusses 12 modifiable risk factors — low education, hypertension, hearing impairment, smoking, midlife obesity, depression, physical inactivity, diabetes, social isolation, excessive alcohol consumption, head injury and air pollution — which are associated with around 40% of worldwide dementia cases.

- Risk Reduction of Cognitive Decline and Dementia, published by the World Health Organization in February 2019, has evidence-based recommendations of lifestyle behaviors and interventions to help delay or prevent dementia.

- Alzheimer’s Disease in African American Individuals: Increased Incidence or Not Enough Data? published in Nature Review Neurology in December 2021, offers three obstacles in understanding racial differences in Alzheimer’s disease: Uncertainty about diagnostic criteria, cross-sectional and longitudinal findings that are not comparable, and a lack of neuropathological data. It also highlights strategies to move the field forward.

- Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementia by Sex and Race/Ethnicity: The Multiethnic Cohort Study, published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia in December 2021, analyzes data from 16,410 Medicare claims between 1999 and 2014 by sex and race or ethnicity. It shows that the rate of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the U.S. was 17 per 1,000 in women, compared with 15.3 in men. The rate was 22.9 among African American women and 21.5 among African American men; for Native Hawaiians, 19.3 in women and 19.4 in men; for Latinos, 16.8 in women and 14.7 in men; for whites 16.4 in women and 15.5 in men; for Japanese Americans, 14.8 in women and 13.8 in men; and for Filipinos 12.5 in women and 9.7 in men.

- Impact of Dementia: Health Disparities, Population Trends, Care Interventions, and Economic Costs, published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society in July 2021, discusses population trends, care interventions, economic impacts, health disparities and implications for future research from information presented at the 2020 National Research Summit on Care, Services, and Supports for Persons with Dementia and Their Caregivers.

- The World Alzheimer Reports by Alzheimer’s Disease International is a source of global socioeconomic information on dementia. Each report is on a different topic.

- The National Press Foundation has a collection of expert presentations on dementia, which can help journalists find sources and story ideas.

- How health affects voter turnout: A research roundup, published by The Journalist’s Resource in 2018, gathers research on connections between health and voting.

- In end-of-life care for people with dementia, men and women are treated differently, published by The Journalist’s Resource in 2019, focuses on a study of 27,243 nursing home residents in Ontario, Canada. The study finds many people with advanced dementia — and men in particular — receive medical interventions that researchers deem burdensome in the final month of life.

- The FDA’s accelerated approval process: When drugs are cleared for sale based on limited evidence, published by The Journalist’s Resource in 2021, explains how the accelerate approval process works — including examples of successes and controversies.

Expert Commentary