A March 2015 report from the Brookings Institution estimates that there at least 46,000 Twitter accounts run by supporters of the Islamic State (also known as ISIS or ISIL), a group of violent extremists that currently occupies parts of Syria and Iraq. This group has also taken to posting violent videos and recruiting materials on many other digital platforms, posing a dilemma for Silicon Valley companies — YouTube, Google, Facebook and the like — as well as traditional news publishers. Facebook, for example, has grappled with whether or not to allow videos of beheadings to be viewed on its platform, and on March 16, 2015, again modified its “community standards.”

Although rising connectivity has helped make these problems more acute in the past few years, terrorism analysts have long been theorizing about an international media war and a globalized insurgency. The RAND Corporation has documented the unique radicalization process now taking place in the digital era.

The dilemmas are personal for many organizations: ISIS has not only executed journalists but has even threatened employees of Twitter who seek to block accounts promoting violence. For news media, there are hard questions about when exactly propaganda is itself newsworthy and when reporting on it serves a larger public purpose that justifies allowing access to a mass audience and amplifying a violent message, however well contextualized. This has led to questions about whether the slick production and deft use of media by ISIS is indeed just a form of “gaming” journalists. Of course, reporting on terrorism in a globalized media environment has been the subject of much debate and research since the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks; the press has faced steady criticism for focusing too much on relatively rare violent acts while neglecting other aspects of the Muslim world, and for hyping threats and helping to sow fear.

Meanwhile, social-media companies have been called on to be more aggressive with those seeking to incite violence. All of these companies have “terms of service” policies: Twitter forbids “direct, specific threats of violence”; YouTube states that it’s “not okay to post violent or gory content that’s primarily intended to be shocking”; and Facebook specifies that it does not allow “terrorist activity” and “organized criminal activity” and states that “supporting or praising leaders of those same organizations, or condoning their violent activities, is not allowed.”

Because of the volume of materials posted, however, these companies often must rely on users reporting problematic content, and their philosophy is generally to err on the side of openness. In an important 2014 paper published in New Media & Society, Kate Crawford of Microsoft Research and Tarleton Gillespie of Cornell analyze this evolving culture of “flagging” content and problems associated with enforcement and transparency.

At the same time, as extremists broadcast messages, they open themselves up to scrutiny, a situation being taken advantage of both by the U.S government (see DARPA’s Social Media in Strategic Communication program) and researchers (for example, the University of Arizona’s Dark Web Project). In a post-Edward Snowden/NSA leaks world, of course, government programs relating to social media analysis are not without controversy.

The SITE Intelligence Group monitors jihadist threats and interprets online messages, while the University of Maryland’s START program provides data on a wide variety of extremist activities.

The following papers and studies help further contextualize these issues:

______

“The ISIS Twitter Census: Defining and Describing the Population of ISIS Supporters on Twitter”

J.M. Berger and Jonathon Morgan, Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World Analysis Paper, No. 20, March 2015.

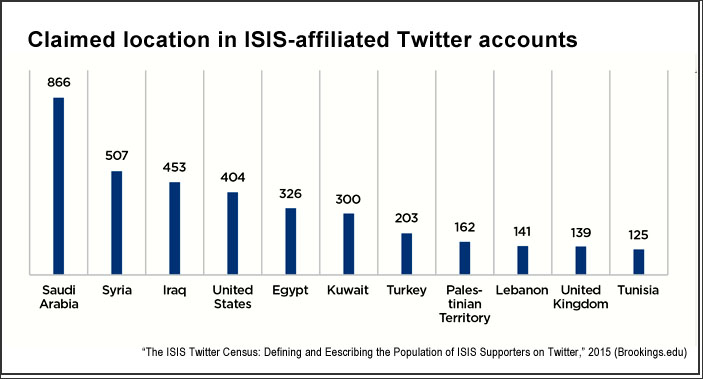

Excerpt: “From September through December 2014, the authors estimate that at least 46,000 Twitter accounts were used by ISIS supporters, although not all of them were active at the same time. Typical ISIS supporters were located within the organization’s territories in Syria and Iraq, as well as in regions contested by ISIS. Hundreds of ISIS-supporting accounts sent tweets with location metadata embedded. Almost one in five ISIS supporters selected English as their primary language when using Twitter. Three-quarters selected Arabic. ISIS-supporting accounts had an average of about 1,000 followers each, considerably higher than an ordinary Twitter user. ISIS-supporting accounts were also considerably more active than non-supporting users. A minimum of 1,000 ISIS-supporting accounts were suspended by Twitter between September and December 2014. Accounts that tweeted most often and had the most followers were most likely to be suspended. Much of ISIS’s social-media success can be attributed to a relatively small group of hyperactive users, numbering between 500 and 2,000 accounts, which tweet in concentrated bursts of high volume.”

“Tweeting the Jihad: Social Media Networks of Western Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq”

Jytte Klausen. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 2015, 38:1, 1-22. doi: 10.1080/1057610X.2014.974948

Excerpt: “Social media have played an essential role in the jihadists’ operational strategy in Syria and Iraq, and beyond. Twitter in particular has been used to drive communications over other social media platforms. Twitter streams from the insurgency may give the illusion of authenticity, as a spontaneous activity of a generation accustomed to using their cell phones for self-publication, but to what extent is access and content controlled? Over a period of three months, from January through March 2014, information was collected from the Twitter accounts of 59 Western-origin fighters known to be in Syria. Using a snowball method, the 59 starter accounts were used to collect data about the most popular accounts in the network-at-large. Social network analysis on the data collated about Twitter users in the Western Syria-based fighters points to the controlling role played by feeder accounts belonging to terrorist organizations in the insurgency zone, and by Europe-based organizational accounts associated with the banned British organization, Al Muhajiroun, and in particular the London-based preacher, Anjem Choudary.”

“Radicalisation in the Digital Era: The Use of the Internet in 15 Cases of Terrorism and Extremism”

Ines von Behr, Anaïs Reding, Charlie Edwards, Luke Gribbon. RAND Corporation, RAND Europe, 2013.

Excerpt: “Evidence from the primary research conducted confirmed that the internet played a role in the radicalization process of the violent extremists and terrorists whose cases we studied. The evidence enabled the research team to explore the extent to which the five main hypotheses that emerged from the literature in relation to the alleged role of the internet in radicalization held in these case examinations. The summary findings are briefly presented here and discussed in greater detail in the full report that follows: The internet creates more opportunities to become radicalized. Firstly, our research supports the suggestion that the internet may enhance opportunities to become radicalized, as a result of being available to many people, and enabling connection with like-minded individuals from across the world 24/7. For all 15 individuals that we researched, the internet had been a key source of information, communication and of propaganda for their extremist beliefs.”

“The Media Strategy of ISIS”

James P. Farwell. Survival: Global Politics and Strategy, 2014, 56:6, 49-55. doi: 10.1080/00396338.2014.985436.

Excerpt: “ISIS leaders seem to recognize that social media is a double-edged sword. The group tries to protect the identity and location of its leadership by minimizing electronic communications among top cadres and using couriers to deliver command-and-control messages by hand. Social media is reserved for propaganda. Still, advances in technology may eventually leave the group vulnerable to cyber attacks, similar to those reportedly urged by US intelligence sources to intercept and seize funds controlled by Mexican drug cartels. Ultimately, defeating ISIS will require focused efforts aimed at discrediting and delegitimizing the group among Muslims, while working towards the only long-term solution for the evil the group has brought to the world: eradication. One hopes the policymakers building coalitions and launching strikes against ISIS have these aims in mind, and will calibrate their narratives, themes and messages accordingly.”

“Making ‘Noise’ Online: An Analysis of the Say No to Terror Online Campaign”

Anne Aly; Dana Weimann-Saks; Gabriel Weimann. Perspectives on Terrorism, 2014, Vol. 8, Issue 5.

Excerpt: “A consideration of terrorism as communication necessarily draws attention to the development of counter narratives as a strategy for interrupting the process by which individuals become radicalized towards violent extremism. As the Internet has become a critical medium for psychological warfare by terrorists, some attempts have been made to challenge terroristic narratives through online social marketing and public information campaigns that offer alternative narratives to the terrorists’ online audiences. ‘Say No to Terror’ is one such campaign. This article reports on a study that examined the master narratives in the ‘Say No to Terror’ online campaign and applied concepts of ‘noise’ and persuasion in order to assess whether the key elements of the ‘Say No to Terror’ campaign align with the application of “noise” as a counter strategy against terrorists’ appeal on the Internet. The study found that while the master narratives of ‘Say No to Terror’ align with suggestions based on empirical research for the development of effective counter campaigns, the campaign does not meet the essential criteria for effective noise.”

“Rhetorical Charms: The Promise and Pitfalls of Humor and Ridicule as Strategies to Counter Extremist Narratives”

L. Goodall, Jr.; Pauline Hope Cheong; Kristin Fleischer; Steven R. Corman. Perspectives on Terrorism, 2012, Volume 6, Issue 1.

Excerpt: “In this article we provide a brief account of the uses of humor, in particular satire and ridicule, to counter extremist narratives and heroes. We frame the appeals of humor as “rhetorical charms,” or stylistic seductions based on surprising uses of language and/or images designed to provoke laughter, disrupt ordinary arguments, and counter taken-for-granted truths, that contribute to new sources of influence to the globally wired world of terrorism. We offer two recent examples of how the Internet in particular changed the narrative landscape in ways that offer potent evidence of uses of humor to remake extremist heroes into objects of derision. We also caution those who would make use of humor as a strategic communication device to take into account the negative side effects and unexpected consequences that can accompany such uses.”

“Detecting Linguistic Markers for Radical Violence in Social Media”

Katie Cohen; Fredrik Johansson; Lisa Kaati; Jonas Clausen Mork. Terrorism and Political Violence, 26:1, 246-256. doi: 10.1080/09546553.2014.849948.

Excerpt: “Lone-wolf terrorism is a threat to the security of modern society, as was tragically shown in Norway on July 22, 2011, when Anders Behring Breivik carried out two terrorist attacks that resulted in a total of 77 deaths. Since lone wolves are acting on their own, information about them cannot be collected using traditional police methods such as infiltration or wiretapping. One way to attempt to discover them before it is too late is to search for various ‘‘weak signals’’ on the Internet, such as digital traces left in extremist web forums. With the right tools and techniques, such traces can be collected and analyzed. In this work, we focus on tools and techniques that can be used to detect weak signals in the form of linguistic markers for potential lone wolf terrorism.”

“Social Network Analysis: A Case Study of the Islamist Terrorist Network”

Richard M. Medina. Security Journal, Vol. 27, 1, 97–121.

Excerpt: “Social Network Analysis is a compilation of methods used to identify and analyze patterns in social network systems. This article serves as a primer on foundational social network concepts and analyses and builds a case study on the global Islamist terrorist network to illustrate the use and usefulness of these methods. The Islamist terrorist network is a system composed of multiple terrorist organizations that are socially connected and work toward the same goals. This research utilizes traditional social network, as well as small-world, and scale-free analyses to characterize this system on individual, network and systemic levels. Leaders in the network are identified based on their positions in the social network and the network structure is categorized. Finally, two vital nodes in the network are removed and this version of the network is compared with the previous version to make implications of strengths, weaknesses and vulnerabilities. The Islamist terrorist network structure is found to be a resilient and efficient structure, even with important social nodes removed. Implications for counterterrorism are given from the results of each analysis.”

Keywords: research roundup, terrorism, surveillance, social media

Expert Commentary