Journalism has undergone many changes over the past five decades, revolutionized once by the television and then again by the Internet. Watergate also played a role in altering the role of the press, as reporters became more aggressive and hard-hitting and increasingly critical of government leaders.

Yet, there’s one important shift that has gone under-reported in the evaluation of media — and that’s the rise of more analytical news articles. In the 1950s stories were largely focused on the “who, what, where and when,” but today articles are increasingly providing the backstory. As a consequence, readers are getting much more than just the facts: They are getting the “so what” and “why.”

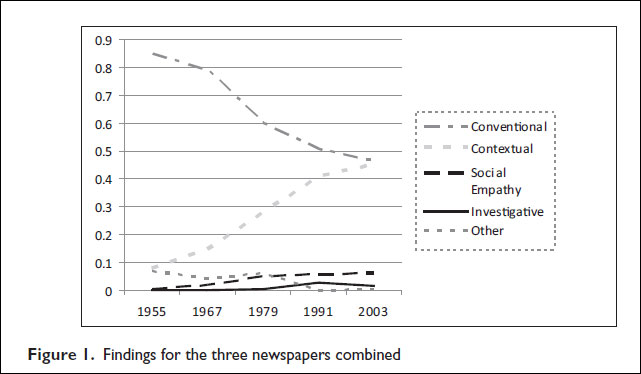

Labeling this new style of reporting “contextual journalism,” scholars Katherine Fink and Michael Schudson of Columbia University tracked three newspapers — the New York Times, the Washington Post and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel — for the years 1955, 1967, 1979, 1991 and 2003. The researchers performed a content analysis on about 1,900 individual stories, grouping them by genre or type. In the resulting 2013 study, “The Rise of Contextual Journalism, 1950s-2000s,” which appeared in the academic publication Journalism, the authors found that journalists were increasingly supplementing the hard facts of a story with interpretation.

The study’s findings include:

- ‘”Contextual reporting,” characterized by greater analysis and interpretation, grew from just under 10% of all articles in 1955 to about 40% in 2003.

- Conventional news stories, which focus on the “who, what, when, and where,” declined from 80% or 90% in all three publications to about 50% over the same period.

- The number of articles per page declined 53%, from 13.5 in 1955 to 7.3 in 2003. Part of the drop can be attributed to the increased length in articles, but part to the addition of photos and promotional material as newspapers strove to mirror the visual stimulation of television.

- Although the number of investigative stories on the front page has increased over time — there were none in the 1955 sample examined, but seven in 1991 and four in 2003 — there continue to be very few investigative articles due to the time and effort required to produce them.

- Social empathy stories increased from 1% of all coverage to 6% in 1991; the level remained at 6% in 2003.

Although some argue that appending commentary to news stories may violate conventional journalistic standards and norms (that reporters should present just the facts), Jonathan Stray writes in an article for Harvard University’s Nieman Journalism Lab that this shift may be appropriate. “No one needs a news organization to know what the White House is saying when all press briefings are posted on YouTube,” he writes. “What we do need is someone to tell us what it means. In other words, journalism must move up the information food chain.”

Fink and Schudson argue that the verdict on whether the shift toward “contextual journalism” is positive is still up for debate: “Contextual journalism has emerged as a powerful and prevalent companion to conventional reporting. Its impact on how people understand their world has yet to be explored.”

The study provides the following chart to illustrate these trends:

Tags: news

Expert Commentary