Long underrepresented across the economy and society, nearly 60% of women now participate in the workforce, and those under age 30 are more likely to graduate from college than their male counterparts. Among younger women, parity in terms of wages and opportunities appears to be much closer than it was for previous generations of women.

Despite this progress, an overall gender wage gap persists — on average, women earn as little as 77 cents for every dollar a man earns (this is a tricky number however, as fact-checking institutions continue to point out). Numerous studies have searched for the gender wage gap’s underlying causes, and explanations have ranged from an underrepresentation of women on corporate boards to inadequate state-level social services programs, from increased family responsibilities to discriminatory language in job postings.

A 2014 study published in the American Sociological Review looks at the role that “overwork” plays in the gender wage gap in the United States. The researchers — Youngjoo Cha of Indiana University and Kim A. Weeden of Cornell University — defined overwork as consistently working at least 50 hours per week. The study, “Overwork and the Slow Convergence in the Gender Gap in Wages,” is based on surveys administered by the Bureau of Labor Statistics between 1979 and 2009 and includes data on nearly 5 million non-military workers ages 18 to 64. They note that progress toward closing the wage gap began to stall in the 2000s, and they examine how new patterns of work generally may reinforce old patterns.

The study’s findings include:

- Men were much likely to work long hours compared to women over the study period — in 2007, 17% of men worked at least 50 hours per week while only 7% of women did.

- Beginning in the mid-1990s, employees working long hours began to earn more money on average than other full-time workers. By 2009, both men and women who overworked earned 6% more than their peers.

- In the 1980s and 1990s, overwork became much more common. “Trends in overwork and their effect on the gender gap in wages are especially consequential for understanding the especially slow change in the gender wage gap in managerial occupations and the slight increase in the gender wage gap in the professions since the early 1990s.”

- The growing prevalence of overwork accounts for an estimated 10% of the gender wage gap observed by 2007.

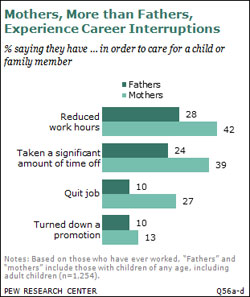

One empirical puzzle remains the persistence of the pay gap in the 2000s, despite the relative decline of overwork during that period, Cha and Weeden note. The researchers hypothesize that, despite popular attitudes that superficially support egalitarianism, women face “essentialist” expectations for “intensive mothering” that now prevail. “In the context of rising relative wages for overwork, gender essentialism about caregiving may exacerbate the motherhood penalty in wages and stagnate the gender wage gap trend by limiting mothers’ ability to benefit from these rising prices.”

One empirical puzzle remains the persistence of the pay gap in the 2000s, despite the relative decline of overwork during that period, Cha and Weeden note. The researchers hypothesize that, despite popular attitudes that superficially support egalitarianism, women face “essentialist” expectations for “intensive mothering” that now prevail. “In the context of rising relative wages for overwork, gender essentialism about caregiving may exacerbate the motherhood penalty in wages and stagnate the gender wage gap trend by limiting mothers’ ability to benefit from these rising prices.”

As for the study’s findings more generally, they conclude: “For all the attention devoted to education and labor market experience in the gender inequality literature, our findings show that growing work hours and compensation of overwork is equally important to understanding trends in the gender wage gap.”

Related research: Harvard’s Claudia Goldin also lays out the case for why temporal flexibility in job structure is the last remaining hurdle for women to achieve pay parity, while Hannah Riley Bowles has investigated the gender dynamics of negotiating over salary. The Pew Research Center presents a variety of key facts. Research reviews on women’s leadership in the workplace and work/family balance provide additional perspective on the gender wage gap.

Expert Commentary