Bullying is as old as humankind and, unfortunately, as new as the Internet. It’s found on playgrounds and in classrooms, on popular sites like Facebook and ask.fm, and can even play out through non-consensual “sexting.” U.S. state laws aimed at reducing bullying vary widely, often because their definitions of such behavior differ. Many states focus on specific actions, others look at the intent or motivation of the aggressor, while some focus on the degree and nature of harm done.

To better understand its roots, impacts and consequences, a broad range of studies have looked at various aspects of bullying behavior. A 2011 study in the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry looked at the correlation between low theory of mind — an individual’s ability to interpret correctly the mental and emotional states of others — and bullying experiences. Other research has considered whether bullying is a potential warning sign of school violence, and the possibility that violent video game play could contribute to youth aggression.

A 2013 study in Psychological Science, “Impact of Bullying in Childhood on Adult Health, Wealth, Crime and Social Outcomes,” looks at the long-term effects of childhood bullying on victims and perpetrators. The researchers — Dieter Wolke of the University of Warwick and William E. Copeland, Adrian Angold and E. Jane Costello of Duke University — defined bullying as a “systematic abuse of power and [it] refers to repeated aggression against another person that is intentional and involves an imbalance of power.” Bullied children were often found to be those who were “withdrawn, physically weak, or prone to show a reaction (e.g., run away, become upset), who have poor social understanding or who have few or no friends who can stand up for them.” Bullies, on the other hand, “have high social impact in school despite being controversial (i.e., liked by some children but disliked by their victims), come from disturbed families, and are deviant in their behavior but not emotionally troubled.” Children who are both victims of bullying and perpetrators “seem to be the most troubled: impulsive, easily provoked, low in self-esteem, poor at understanding social cues, and unpopular with peers.”

The researchers based the current research on a sample of 1,420 North Carolina children in three groups (ages 9, 11 and 13) who were enrolled in the Great Smoky Mountains longitudinal population-based study in 1993. The children completed annual assessments with their primary caregivers until age 16, and then were surveyed again a decade later. They were assessed for involvement in bullying in childhood and then assessed as young adults for health, risky behavior, wealth and social relationships.

The study’s findings include:

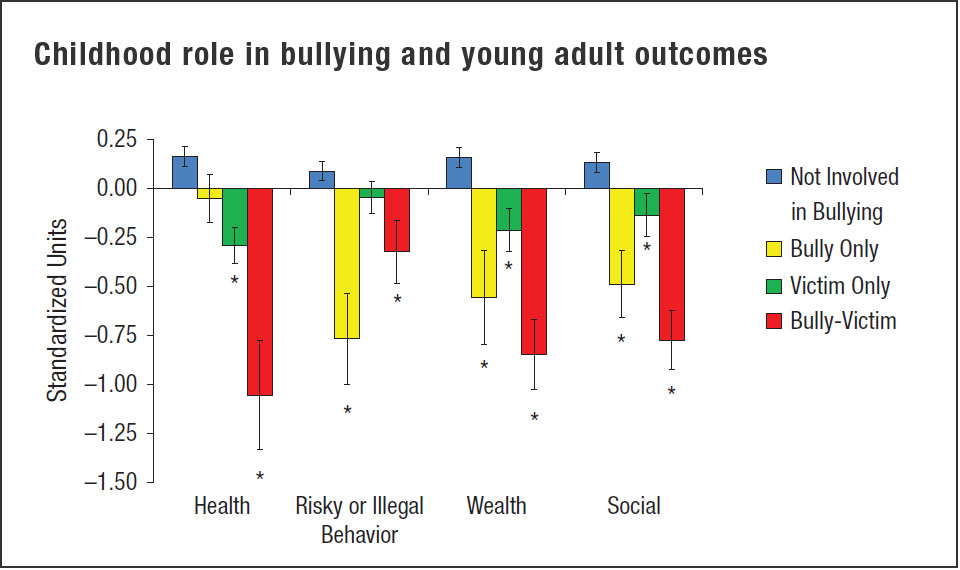

- Involvement with bullying in any role — bully, victim, or bully-victim — was associated with negative financial, health, behavioral and social outcomes later in life. Even when the researchers adjusted for family hardship and childhood psychiatric disorders, “risk of impaired health, wealth, and social relationships in adulthood continued to be elevated in victims and bully-victims.”

- Bully-victims exhibited the greatest overall long-term impairment, including “the worst health outcomes in adulthood (increased rates of poor outcomes on six of nine indices), with markedly increased likelihood of having been diagnosed with a serious illness, having been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder, regular smoking, and slow recovery from illness.”

- Bullies were at high risk for later psychiatric problems, regular smoking, and risky or illegal behaviors, including felonies, substance use and self-reported illegal behavior.

- All groups showed elevated problems with financial-educational functioning. “Bullies had elevated rates of four of seven outcomes, bully-victims of six outcomes, and victims of three outcomes. All groups were at risk for being impoverished in young adulthood and having difficulty keeping jobs. Both bullies and bully-victims displayed impaired educational attainment. There were no significant differences across groups in the likelihood of being married, having children, or being divorced, but social relationships were disrupted for all subjects who had bullied or been bullied.”

- Involvement of any kind in these events proves to have long-term consequences: “Being a victim or, in particular, a bully-victim continued to be an independent predictor of diminished health, wealth, and social relationships in adulthood.”

- “Of the 421 victims and bully-victims, 159 (37.8%) were chronically bullied…. Direct comparisons of chronically bullied victims and victims bullied at only one time point revealed that the chronically bullied subjects had significantly higher levels of social problems (p = .046) and showed a trend toward greater financial problems (p = .083).”

The researchers note that while the sample is not representative of the U.S. population — blacks were underrepresented and American Indians overrepresented — “the prevalence rates of bullying and peer victimization reported by subjects of the present study in childhood are similar to rates reported in population-based studies.”

Keywords: bullying, youth

Expert Commentary