With more than 1.8 million passengers traveling through United States airports each day, each passenger cannot be screened as thoroughly as security officials would like. Therefore, many airports have resorted to passenger profiling to target travelers who appear to be a threat. Although controversial, passenger profiling has a long history in the United States. Airports relied heavily on profiling before metal detectors were introduced in 1973 and security administrators admit that, even today, travelers from certain countries (and who exhibit certain behavior) may be subject to further search.

The balancing of security concerns with respect for the dignity and liberties of the persons traveling — and not unnecessarily creating psychological and social harm — represents a significant challenge for all nations. As the New York Times reports, new measures proposed by the United States in 2013 to distinguish “trusted travelers” from more perceived high-risk passengers have raised significant civil liberties concerns.

No country has more experience with the difficult dynamics of airport security than Israel, and as the authors of a 2012 study published in the American Law and Economics Review point out, the country is “likely to be the world’s frontier on the topic.” That study, “Ethnic Profiling in Airport Screening: Lessons from Israel, 1968-2010,” considers the implications of ethnic profiling in airport screening practices. Using data collected from Israel’s Ben-Gurion Airport — the first country in the world to introduce airport security — the researchers, from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Tel Aviv University and the Radzyner School of Law, sought to better understand the equity costs entailed by profiling. The researchers interviewed a random sample of 918 passengers prior to boarding; these included 308 Israeli Jews, 306 Palestinians who were Israeli citizens (Israeli Arabs), and 304 non-Israelis.

The study focuses on the idea of “expressive harm,” whereby “profiling minorities may result in significant equity costs as it reminds the targeted group members of the discrimination against them in other aspects of life.”

The study’s findings include:

- The researchers found the negative feelings toward airport security arose not based on ethnicity of the passenger, but whether the passenger’s bag was opened for further examination and the way in which it was done. Only 9.8% of Israeli Jews were required to open their suitcases for additional searches whereas 40% of the suitcases of Israeli Arabs and non-Israelis were opened for additional searches.

- The findings suggest that “it is only when the security check becomes visibly intrusive that harm is triggered. This means that the way in which the screening is done, that is, making it as tacit as possible, in a patient and polite manner, could significantly reduce costs.”

- Israeli Arab passengers felt that they were treated differently by the airport’s security personnel to a greater extent (33%) than Israeli Jewish passengers (13.4%) and foreign passengers (21%).

- Asked whether airport security checks are justified given Israel’s security situation, 95.4% of Israeli Jews surveyed agreed. By comparison, 80.3% of foreign passengers and 66% of Israeli Arabs agreed. Only 62.4% of Arab passengers reported the treatment during the security checks was fair, compared to 96.1% of Jewish passengers.

- A majority of the respondents (82%) reported that security checks contributed to their sense of safety with only a small difference between Jewish (88%) and Arab (80%) passengers.

- In the Israeli context, the typical profile of a terrorist is a Muslim (88%), Arab (79%), male (87%) and a member of a Palestinian terror organization (91%). This profile comes from an analysis of aviation terror-related data from 1968 to 2010.

The authors conclude that profiling is an important part of airport security, but that overtly doing so in a way that could provoke resentment could be counterproductive. Consequently, they suggest several policies to reduce the negative psychological impacts of extensive screening, including opening suitcases away from the passenger-screening area or in a separate space.

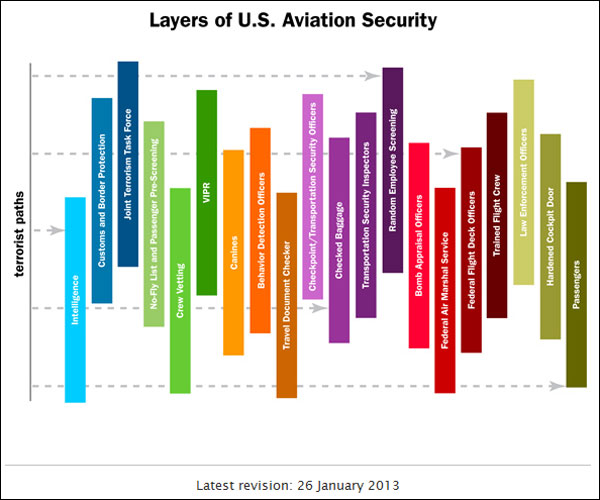

Related: The U.S. Transportation Security Administration, created after the 9/11 attacks to strengthen screening and protection in airports and other travel hubs, offers the following chart to illustrate the various measures it takes:

Tags: terrorism, Middle East, civil rights

Expert Commentary