The U.S. Department of Justice issued a memo on Aug. 29, 2013, advising state attorneys general that it would not try to block laws that allow for some legal medical and recreational marijuana use. In 2012, voters in the states of Washington and Colorado approved the decriminalization of small amounts of recreational marijuana use; 18 other states and Washington, D.C., allow for some medicinal usage. The decision immediately drew strong criticism from a coalition of law enforcement organizations, which sent a letter of complaint to Attorney General Eric Holder.

In that letter, the coalition of sheriffs, police chiefs and other officers involved in drug investigations note that marijuana usage can impair people’s ability to drive automobiles, and asserted that its use is generally associated with crime. For its part, the Department of Justice acknowledges the problems with impaired driving as well as associations with crime and criminal networks, and says curbing these phenomena remains a priority. But the law-enforcement group letter goes even further, claiming that “marijuana’s harmful effects can include episodes of depression, suicidal thoughts, attention deficit issues.” (It should be noted that not all law enforcement officers or groups agree with these critiques.)

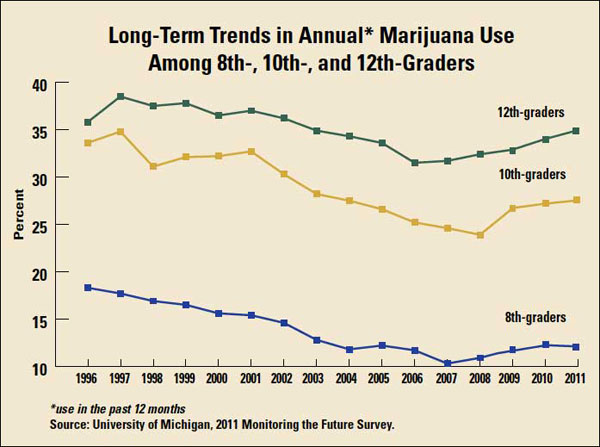

Setting aside the questions about criminal or negligent behavior and the merits of medical use, what is the scientific evidence for these general claims about the cognitive effects of pot? Broadly speaking, the medical research literature has noted some problems for heavy users and persons who begin significant use of marijuana at a young age. A 2014 study published in the Journal of Addiction Medicine found troubling evidence of problems with addiction among adolescents (this comes as survey research suggests daily pot use is up among some younger populations such as college students.) But recent medical research has weighed some of the evidence and surfaced further nuances in the conclusions about cognitive effects.

The research in this area is evolving and single studies — even those published in top journals — come under a lot of scrutiny, given the political stakes. For example, a 2012 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, “Persistent Cannabis Users Show Neuropsychological Decline from Childhood to Midlife,” found evidence that long-term use of marijuana early in life led to declines in IQ scores. But the sample size and other elements were criticized in some quarters, and the authors themselves note several limitations.

For obvious reasons, there have not been large-scale randomized control trials in laboratory conditions — the gold-standard for medical and scientific research — and therefore a great deal of the research on marijuana comes with caveats. In addition, leading experts such as Mark A.R. Kleiman of UCLA acknowledge the public health drawbacks but note that any serious policy analysis must take into account multiple other considerations. In a 2011 review article in the journal Addiction, Kleiman states:

Damage to physical and mental health, although relatively low per dose, is magnified by the large number of users, and especially of heavy users. The numbers of cannabis users ‘in need of treatment’ by clinical standards, and of those actually entering treatment, rank high compared to other illicit drugs, although far lower than for alcohol. Early initiation of use — an identified risk factor for various forms of damage — is a widespread concern, with the median age of initiation in some countries hovering around 16 years. The potency of cannabis in terms of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content has been rising, along with the ratio of THC to cannabidiol….

A full analysis of cannabis policy would work forward from (i) formal policies embodied in statutes, regulations and the budgets and administrative rules of public agencies, to (ii) policies-in-practice (e.g. of enforcement) carried out by officials, to (iii) conditions influencing cannabis use (such as price, availability, legal risks faced by users and attitudes), to (iv) use itself, to (v) harms associated with use (vi), harms associated with illicit commerce and (vii) to harms associated with enforcement, including both budget costs and the damage resulting from punishment.

The following is a representative sample of academic studies relating to the cognitive and personal health aspects of the issue:

Depression

A June 2013 metastudy — an examination of prior scholarly research — published in Psychological Medicine analyzed the 14 most rigorous studies available that, combined, looked at results for more than 76,000 subjects. The paper, conducted by a team of researchers at the University of Toronto and several other institutions, represents the “current state of knowledge on this association.” The research accounts for a number of problems that have weakened other single studies, such as small sample sizes or study groups where persons with other mental health problems were over-represented. The 2013 metastudy, titled “The Association between Cannabis Use and Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Longitudinal Studies,” finds: “Cannabis use was associated with a modest increased risk for developing depressive disorders…. [H]eavy cannabis use was associated with a stronger, but still moderate, increased risk for developing depression. These associations … were consistent for cannabis use both in adolescence and in adulthood.”

However, the researchers concede that existing research has not fully accounted for a number of variables — including how cumulative exposure works, and types of marijuana used — and, overall, “results pertaining to increased risk for depression among cannabis users should be regarded with caution.”

It should also be noted that other newer research, such as a 2012 study in the journal BMC Psychiatry, finds no relationship between cannabis and depression, but establishes a link with “psychosis” (although even the psychosis connection remains contested and in need of more research.) A December 2013 study published in Schizophrenia Bulletin finds some connection between heavy marijuana use during teenage years and severe mental illness, though the study’s authors note that more long-term research is needed to definitively confirm the results and establish a firm causal relationship.

Suicide

A 2012 study published in the journal Addictive Behaviors, “Daily Marijuana Use and Suicidality: The Unique Impact of Social Anxiety,” notes that research has demonstrated a “clear relationship” between cannabis and suicide, but medical scientists have established relatively little about the precise connection or exactly why it is such a “risk factor.” That study suggests that certain additional factors, such as underlying levels of social anxiety, are truly what make regular marijuana users more likely to be suicidal. It also suggests the difficulty of separating out marijuana’s exact role in fostering suicidal tendencies. Further, a May 2013 study in the Journal of Health Economics, finds that “using cannabis at least several times a week leads to suicidal ideation in susceptible males. [But] we find that … suicidal ideation does not lead to cannabis use for either males or females.”

Still, as noted in a 2009 research paper in the Journal of Forensic Sciences, an analysis of toxicology reports suggests that victims of suicide are more likely to have used marijuana. However, there is very credible research, such as a 2009 study in the British Journal of Psychiatry, that casts doubt on any direct link between cannabis use and suicide.

Attention deficit issues

If by “attention deficit issues” one means a general diminishing of cognitive functioning, there is medical research that supports the notion that cannabis can negatively affect one’s memory and learning ability both during and after use. However, when researchers speak of a cannabis-attention deficit connection, they frequently refer to the cultural phenomenon — still controversial — of people with ADHD using marijuana to “self-medicate.” It is, in any case, a complicated matter. An August 2013 study published in Psychiatry Research, which examined a relatively small number of subjects (56 men, 20 women), yields interesting findings but also underscores the challenge of proving the exact relationship and disentangling variables: “Significant correlation between greater frequency of marijuana use and increased number of inattentive symptoms was found in men, but not in women with ADHD. Although men with ADHD showed a stronger correlation than women, the correlation coefficients were not significantly different between genders. Previous research suggested that individuals with ADHD may use marijuana to treat their symptoms … and our findings may support this hypothesis in men. Alternatively, increased marijuana use may negatively affect inattention in men, and to a lesser degree in women with ADHD. Clearly, more research is necessary to examine the causal effects of marijuana on ADHD symptoms.”

Any causal connection is also complicated by the fact that people with substance-use disorders in general are more likely to be afflicted with ADHD, and vice versa, as suggested by a 2012 metastudy in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence.

Keywords: drugs, cognition

Expert Commentary