In North America the winter of 2014-2015 was one for the record books — in particular, 108.6 inches of snow fell in Boston, breaking a longstanding record. But melting snow can bring rising waters, as indicated by a March 2015 report from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which highlighted the approaching flood risks for New England and Upstate New York as well as for southern Missouri, Illinois and Indiana.

The role of human-induced climate change in the increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events is well established. The 2014 Vermont Climate Assessment found that since 1960 average temperatures in that state have climbed 1.3 degrees and annual precipitation by nearly 6 inches, with the majority of the increase occurring after 1990. The 2011 Vermont floods and those in North Dakota in 2009 show how devastating such events can be. The projected rise in sea levels will also create profound challenges for coastal communities large and small.

According to a 2013 report from the Congressional Research Service (CRS), just 18% of Americans living in flood zones have the required insurance — not comforting news for them or for federal and state governments, charged with providing material and financial disaster relief after the fact. Data from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) indicates that between 2006 and 2010, the average flood claim was nearly $34,000, and large events can impose substantially higher costs. According to the CRS, the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) paid out between $12 and $15 billion after Hurricane Sandy — more than triple the $4 billion in cash and borrowing authority it initially had. Starting in 2016, states seeking to receive disaster-preparedness funds must have plans in place to mitigate the effects of climate change, or risk losing funding, FEMA announced in March 2016.

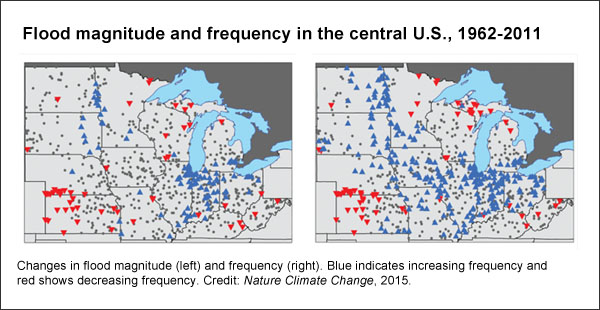

A 2015 study published in Nature Climate Change, “The Changing Nature of Flooding across the Central United States,” examines long-term trends in the frequency and intensity of flood events. The researchers, Iman Mallakpour and Gabriele Villarini of the University of Iowa, used data from 774 stream gauges over the period 1962 to 2011. Gauges had at least 50 years of data with no gaps of more than two continuous years. The 14 states examined were Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North and South Dakota, Ohio, West Virginia and Wisconsin.

The study’s key findings include:

- In the Central United States (CUS) the frequency of flooding events has been increasing, while the magnitude of historic events has been decreasing. Overall, 34% of the stations (264) showed an increasing trend in the number of flood events, 9% (66) a decrease, and 57% (444) no significant change.

- The largest proportion of flood events was in the spring and summer, and 6% of the stations (46) showed increasing trends in the spring, and 30% (227) in the summer. “Most of the flood peaks in the northern part of the CUS tend to occur in the spring and are associated with snow melt, rain falling on frozen ground and rain-on-snow events.”

- Increased flood frequency was concentrated from North Dakota down to Iowa and Missouri, and east to Illinois, Indiana and Ohio. Areas with decreasing flood frequencies were to the southwest (Kansas and Nebraska) and to the northeast (northern Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan).

- “Trends of rising temperature yield an increase in available energy for snow melting, and the observed trends in increasing flood frequency over the Dakotas, Minnesota, Iowa and Wisconsin can, consequently, be related to both increasing temperature and rainfall.”

The researchers note that “a direct attribution of these changes in discharge, precipitation and temperature to human impacts on climate represents a much more complex problem that is very challenging to address using only observational records.” At the same time, “changes in flood behavior along rivers across the CUS can be largely attributed to concomitant changes in rainfall and temperature, with changes in the land surface potentially amplifying this signal.”

Related research: A 2011 metastudy from the Institute for Environmental Studies at Vrije Universiteit in the Netherlands, “Have Disaster Losses Increased Due to Anthropogenic Climate Change?” analyzes the results of 22 peer-reviewed studies on economic losses from weather disasters and the potential connection to human-caused global warming. It found that while economic losses from weather-related natural hazards — including storms, cyclones, floods and wildfires — have increased around the globe, the exposure of costly assets is by far the most important driver.

Keywords: global warming, climate change, flooding, snowfall, rain, precipitation, disasters, water

Expert Commentary