The United States Department of Labor reported some good news in January 2015, with the national unemployment rate falling to 5.6%, the lowest level since June 2008. The total national figure for persons receiving benefits from unemployment insurance programs was 2,405,601 on Dec. 20, 2014, a 57% drop from the 4,205,127 during that same week in 2013.

Despite the positive figures, however, there continue to be several unresolved and troubling dimensions of this recovery. One of the most prominent is the changing nature of wage growth, which has been generally slowing down in recent decades — a phenomenon that has complex roots. But there are other related trends worth reporting on, even as the economy comes back. Research usefully sheds light on some of these issues.

Skills and new jobs

The character of many new jobs produced during the recovery has come under considerable scrutiny. The economy lost many higher-wage jobs during the Great Recession and has since gained many more low-wage jobs, according to an analysis by the National Employment Law Project. Further, as the research institution Re:Gender points out, there has been a huge increase in the number of “independent”/contract workers in the U.S. labor force. This form of work typically has little security.

There are also a significant number of Americans who have found themselves, in effect, “overeducated” relative to the work opportunities available, as Brian Clark and Arnaud Maurel of Duke University and Clement Joubert of UNC Chapel Hill put it in a 2014 paper. A more general “skills mismatch” has also been noted, making the efficient transition from a lost job to a new one more difficult for many workers. Bart Hobijn of the Federal Reserve of San Francisco and Aysegul Sahin of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York note in a 2013 paper:

The displacement of a large part of the labor force during deep recessions results in a shift of the composition of vacancies and an increase in mismatch in the labor market which leads to a decline in measured match efficiency…. [T]he U.S. experience in the wake of the Great Recession perfectly fits this profile, with construction jobs being at the center of both the composition effect and the increase in skill mismatch.

There continues to be a debate about the scope of the skills mismatch and thus the need to retrain significantly large parts of the workforce. (President Obama’s community college initiative, announced in January 2015, is in part a response.) Still, a 2013 study by Andrew Weaver and Paul Osterman of MIT looked at empirical data generated by a survey of U.S. manufacturers and found that the skills gap may be overstated in some instances. They found that:

Basic skill demands are widespread, but that demands for higher-level skills are surprisingly modest. Demands for higher-level reading and math skills are prominent, but those for skills related to high-performance work systems are substantially less so. With regard to skill gaps, three-quarters of establishments show no sign of hiring difficulties. We estimate an upper bound on potential skill gaps of 16% to 25% of manufacturing establishments. This finding contrasts sharply with other, non-representative surveys that have reported figures in excess of 60% or 70%.

The research of Harvard’s Richard B. Freeman has long spoken to these and related issues, while that of his colleague Lawrence Katz has put the skills issue in historical perspective.

Human impacts of unemployment

Perhaps the most troubling aspect of the current economic recovery — the “underside,” as it were — is the large cohort of Americans who have simply stopped looking for work and who are effectively no longer part of the labor force (as distinguished from the long-term unemployed who are still technically looking for work and are available). Beyond the economic burden that protracted joblessness places on families and the increased chances of falling into the poverty trap — the poverty rate has also remained stubbornly high in recent decades — unemployment frequently results in deep emotional distress. As Cristobal Young of Stanford has noted, job loss “amounts to a highly visible and stigmatizing loss of personal identity.”

The New York Times has created a visualization of what life often looks like for the jobless, and scholars have even attributed an increase in suicide to the Great Recession. Financial insecurity also has a range of secondary effects for communities, including, as the Pew Research Center recently noted, diminished participation in civic and political life.

The “missing workers” problem

The size of this “missing workers” cohort in the United States is estimated to be well into the millions. The liberal-leaning Economic Policy Institute puts the missing-workers figure at 5.76 million, while the conservative-leaning Heritage Foundation finds that 6.9 million fewer Americans are working or searching for work since the recession began. But this jobless group’s exact dimensions are difficult to pin down, and in any case, they’re not accounted for in the official unemployment rate. (The Labor Department does keep track of “discouraged workers” who are only “marginally attached” to the job market.)

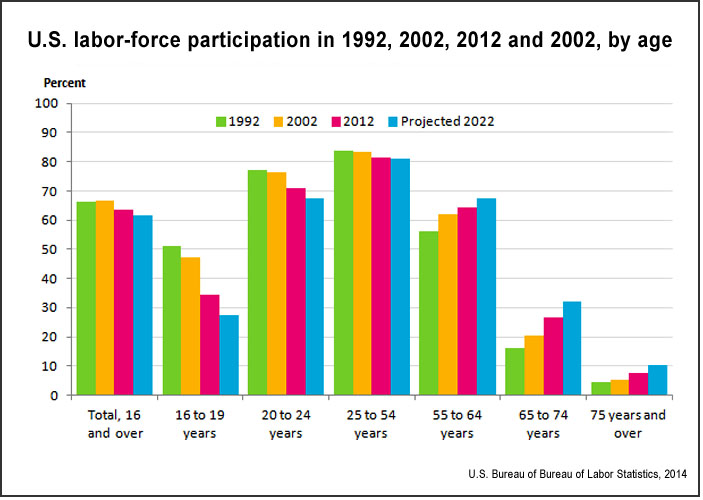

One way to quantify this issue is to look at the labor participation rate, which was 66% before the Great Recession and is down to 62.7% as of December 2014. The Department of Labor projects the rate will continue to fall through 2022 because of demographic shifts:

Why has this labor participation rate — a subject of some political controversy — declined? How much has the economic downturn driven this pattern? The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) states in a 2014 report:

The postrecession decline partly reflects the aging of the baby-boom generation, whose members have been reaching typical retirement ages (the oldest of the group turned 65 in 2011). But it also reflects declining participation within some age groups. For men between the ages of 25 and 54, participation, which had been falling gradually over a period of four decades, fell by another 1.4 percentage points from 2009 to 2013.

A 2014 paper by Willem Van Zandweghe, senior economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, finds that the economic downturn and the population getting older are equally to blame: A “variety of evidence indicates that, on balance, trend factors account for about half of the decline in labor force participation from 2007 to 2011, with cyclical factors acounting for the other half.”

Other trends in American life – two-income households where one adult drops out of the labor force to raise children, as well as the difficulty of capturing patterns relating to undocumented workers — further complicate any easy interpretations of trends in the labor force participation rate.

Chances of working again

What will the strengthening economy of late 2014 and early 2015 mean for those millions who have long been out of the labor force? Time will tell, but empirical research sheds light on this issue, too.

A 2014 paper for the Brookings Institution by three Princeton University scholars, “Are the Long-Term Unemployed on the Margins of the Labor Market?” provides insight into the border region between those who are still looking for work over long periods and those who finally drop out of the labor force altogether. The authors, Alan B. Krueger, Judd Cramer and David Cho, analyze data to pinpoint new trends and make some general observations about this area, including:

- “The long-term unemployed normally have a higher rate of labor-force withdrawal than the short-term unemployed, although following a recession the labor force withdrawal rates for all duration groups tend to collapse to a common, relatively low level.”

- The scholars’ analysis of recent data suggests that the “long-term unemployment rate has remained elevated even in low-unemployment rate states” and that “that the long-term unemployed are faring better in terms of transitioning to employment in the low-unemployment states than in the high-unemployment states.”

- In any given month, the long-term unemployed have about a 1 in 10 chance of returning to the workforce, although “when they do return to work their new jobs are often transitory.” And they frequently only regain employment “in the same occupations and industries from which they were displaced.”

- Overall, the “long-term unemployed will continue to encounter difficulty finding employment even if the unemployment rate continues to fall, although a stronger economy would undoubtedly raise the prospects of the long-term unemployed.”

“Their diverse and varied set of characteristics,” the researchers conclude, “implies that a broad array of policies will be needed to substantially lower the long-term unemployment rate and stem labor force withdrawal, as concentrating on any single occupation, industry, demographic group or region is unlikely to have a substantial impact reducing long-term unemployment by itself.”

Related research: A 2014 paper by Daniel Cooper and María José Luengo-Prado of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, “Labor Market Exit and Re-Entry: Is the United States Poised for a Rebound in the Labor Force Participation Rate?” finds that a “nontrivial share of workers under 45 years of age who exit the labor market appear to re-enter within four years.” A 2014 paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research provides technical insights into the precise mechanisms that explain long-term unemployment and the duration of joblessness. Finally, the Brookings Institution’s Hamilton Project has also been tracking the “jobs gap” — the “number of jobs that the U.S. economy needs to create in order to return to pre-recession employment levels while also absorbing the people who enter the potential labor force each month.” That number stood at 4.6 million in December 2014.

Keywords: unemployment, Great Recession, financial crisis, economy, poverty

Expert Commentary