Like much of the U.S. tax code, the home mortgage interest deduction (MID) has a complex history. Introduced in 1913, its original purpose was to simplify businesses’ tax returns — almost all interest payments a century ago were business-related, so no distinction was needed between professional and personal costs. More than half of Americans rented at the time, and continued to do so until the creation of the Federal Housing Administration in 1934 and its subsequent mortgage-guarantee program. It was only when suburbanization took root in the 1950s that the MID came to be perceived as an essential part of enabling the “American dream” of home ownership, an association encouraged by presidents and partisans alike. Not bad for an “accidental deduction,” as it is described in a 2010 paper from U.C. Davis.

Much has changed since 1913, of course, in particular the tax code. All consumer interest was once deductible, but that went away with the 1986 Tax Reform Act, signed by President Ronald Reagan. Yet MID hangs on, in part thanks to fierce support by the National Association of Realtors and other industry groups. But in an age of high unemployment, falling tax receipts and increasing concerns about Social Security and Medicare, the mortgage-interest deduction has become very expensive: According to a 2013 report from the nonpartisan Center on Budget Priorities, the MID cuts into government revenue by roughly $70 billion a year, but “appears to do little to achieve the goal of expanding homeownership.”

Part of the problem is that the higher one’s tax bracket, the more benefit the deduction provides. And to even claim it, taxpayers must itemize their returns, yet few lower-income Americans do. As a consequence of these and other factors, more than 75% of the MID’s benefits go to households with incomes over $100,000, and often for second homes, according to the CBP. Given the sharp rise in income inequality in the United States, the desire to address the growing federal deficit, and other issues, Congress has shown a willingness to revisit what has been called the “third rail” of the U.S. tax code. In February 2014, Dave Camp, chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, unveiled a plan that would have cut the mortgage limit in half, to $500,000. While the plan’s reception was chilly, some adjustment to the MID seems inevitable in the long term, particularly within a larger tax reform.

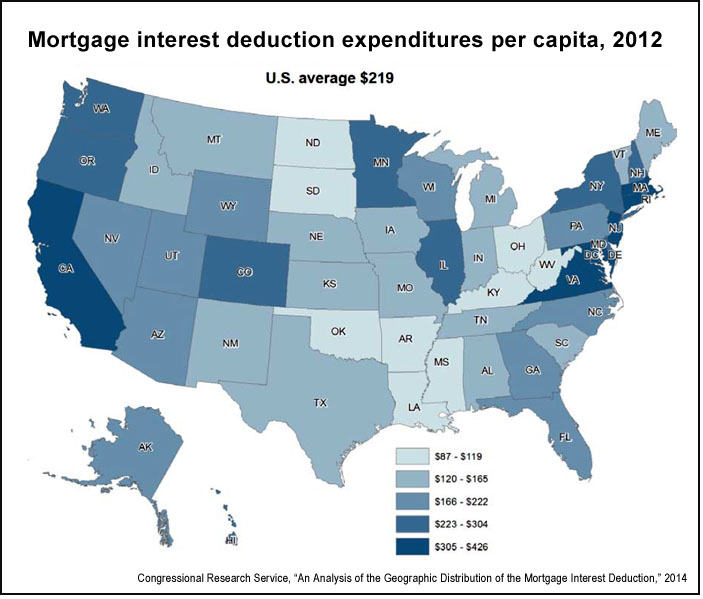

A 2014 report from the Congressional Research Service (CRS), “An Analysis of the Geographic Distribution of the Mortgage Interest Deduction,” looks at variations in the deduction’s use from state to state. The purpose of the report, authored by Mark P. Keightley, is to help Congress better understand the potential impact of any tax-reform plan.

The study’s findings include:

- Because the current mortgage-interest benefit is structured as a deduction, higher-income taxpayers gain more than lower-income ones. For example, someone with a 25% marginal tax bracket would get a tax reduction of $2,500 from $10,000 in mortgage interest; however, higher-income individual in the 35% bracket could deduct $3,500 for the same mortgage.

- Based on figures from the Joint Committee on Taxation, the CRS estimates that the mortgage-interest deduction cut federal tax revenues by $68.5 billion in the 2012 fiscal year. The U.S. per-capita average was $219.

- The states that were the smallest per-capita beneficiaries were Mississippi and West Virginia, just under $90 per person. Residents of Washington, D.C., and Maryland benefited the most, with benefits of $426 and $414 per person, respectively — nearly five times as much.

- On average, 25% of U.S. taxpayers claim the mortgage-interest deduction. Residents of South and North Dakota had the lowest claim rates, under 15%, while the highest rates were found in Connecticut and Maryland, where approximately a third of those filing taxes deducted mortgage interest costs.

- Less than half of all U.S. homeowners claim the deduction, 48%. The reasons can include not having a mortgage, mortgage payments too low to make filing worthwhile or living in a state without an income tax. Louisiana, Mississippi, North and South Dakota and West Virginia had the lowest proportions of homeowners claiming the deduction, while those in California, Colorado, Utah and along the Northeast Corridor had the highest claim rates.

- A related 2013 report from the Pew Center on the States provides some additional specificity on where MID benefits are most frequently claimed and the amount of interest deducted. In particular, there’s a notable “doughnut hole” pattern visible around big cities, indicating that claims in suburbs are both more frequent and larger than those in other areas of the country.

- The average homeownership rate in the United States was 65% in 2011, varying between 41% and 73%. High rates of ownership were observed in states such as Wyoming, Minnesota and Iowa, while California, Nevada and New York had low rates.

- While states with higher homeownership rates should expect to see higher claims rates, that was not found to be the case. Factors in state-to-state variability include home prices, state and local taxes and individual income. Ultimately, “all else equal, markets with higher incomes should be expected to have a higher claim rate.”

The Congressional Research Service Report looks at four policy options considered for the mortgage interest deduction. They are:

- Retain the current deduction. While the deduction is understandably popular with higher-income homeowners and industry groups and is thought to promote homeownership, that is not supported by the evidence: Research “generally suggests that the deduction does not achieve the often-stated policy objective of increasing homeownership,” yet it costs the federal government nearly $70 billion per year.

- Eliminate the deduction. “Elimination of the deduction could improve the overall performance of the economy if the deduction is currently leading labor and capital to be allocated to less-productive uses in the owner-occupied housing sector…. Elimination of the deduction would be a step in the direction of creating more uniformity in the tax treatment of various sectors, which would assist in a more efficient allocation of resources across the economy. The increase in federal revenue from eliminating the deduction could also improve the long-term budgetary situation of the United States, implying less reliance on deficits to finance spending.”

- Limit the deduction. Given the deduction’s oft-stated goal of increasing homeownership, its effectiveness could be increased if it were limited to mortgage amounts more typical of first-time homebuyers. “In 2009, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated the revenue effect of gradually reducing the maximum mortgage amount on which interest can be deducted from $1.1 million to $500,000 [and found that] this option would raise a total of $41.4 billion between enactment (2013) and 2019.”

- Replace the deduction with a credit. Because the benefit is a structured as a deduction, it provides more assistance to higher-income homeowners; a credit, on the other hand, would have the same dollar value of all taxpayers regardless of income. The CRS report analyzes five options, all of which limit the deduction to the principal residence. “Four out of the five would allow a 15% credit rate. Three of the five credit options would be nonrefundable. Two of the options would limit the size of the mortgage eligible for the credit to $500,000, while one would limit eligible mortgages to no greater than $300,000 (with an inflation adjustment). Another option would limit the maximum eligible mortgage to 125% of the area median home prices. And still another would place no cap on the maximum eligible mortgage, but would limit the maximum tax credit one could claim to $25,000.”

“It is important to note that any change to the mortgage interest deduction would likely require careful consideration of how to transition to the new policy so as to minimize disruptions to the housing market and overall economy,” the author writes. “Depending on its design, a policy modification could result in a more evenly distributed benefit to homeowners. The author cites research that suggests that if the deduction were phased out over 15 to 20 years, it would have no effect on demand or prices.

Related research: A 2013 study from the Peterson Institute for International Economics, “Does High Home-Ownership Impair the Labor Market?” found that increasing rates of home-ownership in a state were eventually followed by higher unemployment. The reasons: lower levels of labor mobility, longer commutes and reduced rates of businesses creation. Also of interest is a 2010 paper from the University of California, Davis, “The Accidental Deduction: A History and Critique of the Tax Subsidy for Mortgage Interest.” It found that the MID had undesirable effects such as “distorting the cost of owner-occupied housing relative to other investments, contributing to overinvestment in the asset class and misallocation of capital stock [and] artificially raising housing prices.”

Keywords: homeownership, suburbanization, inequality, consumer affairs, land use, sprawl

Expert Commentary