Before he was elected president in 1992, Bill Clinton ran on a platform of “ending welfare as we know it.” At the time, a New Deal-era program called Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) provided payments to children whose parents were unemployed, deceased, disabled or absent from the household. States administered AFDC and were entitled to unlimited matching funds from the federal government. Critics of AFDC charged that the program was too costly, discouraged parents from finding work and encouraged unmarried women to have children.

President Clinton signed a bill in 1996 that ended AFDC and replaced it with Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF). The new program placed limits on federal welfare spending, prevented parents from receiving funds for more than five years in a lifetime and mandated that recipients enroll in job training “workfare” programs. Clinton’s welfare reform effort was immediately controversial for the potential hardships it posed to low-income Americans. Several high-level officials at the Department of Health and Human Services resigned in protest of the new law.

One way to evaluate welfare reform efforts is to look at employment rates and earnings for individuals who are no longer receiving benefits. A 2002 study in Social Science Review found that 84% of individuals exiting TANF were employed, which was slightly higher than the 81% of former AFDC recipients who were employed. Annual earnings for former TANF recipients were about 15% lower compared to AFDC recipients, however.

Another way to assess the impact of welfare reform is to conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis. Two previous studies of welfare reform randomly assigned families to receive benefits following AFDC guidelines or TANF guidelines. Researchers were able to quantify the cost per beneficiary of each program, but also looked at other outcomes such as recipient mortality. Both studies found that TANF resulted in considerable cost savings for government, but also reduced life expectancies for mothers.

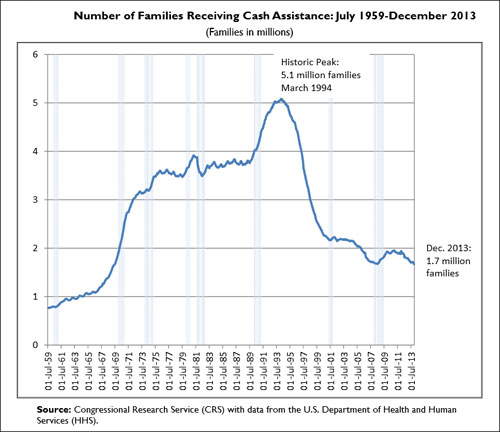

Currently, about 1.7 million American families claim TANF benefits each month; about 75% of the 4 million people receiving benefits are children. Funding is based on an annual $16.5 billion block grant from the federal government, while states also contribute about $10.4 billion.

A 2014 study published in the American Journal of Public Health, “More Money, Fewer Lives: The Cost-Effectiveness of Welfare Reform in the United States,” offers a cost-effectiveness analysis based on data from these previous studies. Columbia University researchers Peter Muennig, Rishi Caleyachetty, Zohn Rosen and Andrew Korotzer estimate the cost of AFDC in terms of years of life gained for the average enrolled mother.

The study’s findings include:

- Over a mother’s working life, receiving AFDC cost the government $28,161 more on average compared to receiving TANF.

- Receiving TANF rather than AFDC led to premature death for some women. Averaged over all program recipients, mothers gained 0.44 years of life from AFDC.

- Relative to TANF, gaining one year of life for the mother from AFDC cost $64,000. The authors compare this measure of cost-effectiveness to that of other public health interventions: “In terms of life-years saved, this is roughly in line with many social interventions in which the government chooses to invest. Examples include emergency floor lighting in airplanes, collapsible steering columns in cars, and airbags in cars. Smoke detectors in homes (at $210,000/life-year saved) roughly correlate with our high estimate of returns on marginal family incomes associated with TANF.”

The authors conclude that the policy changes yielded mixed outcomes: “Welfare reform may have produced very large direct monetary savings, including returns for both individuals and for the US government. However, TANF may also harm women who could not subsequently work (whether as a result of young children at home, large family size, or mental or physical illness). Some may have ended up relying on weak financial networks or become homeless. Given that higher earnings and employment are thought to be beneficial for health, the observed adverse impacts on the mothers and their children likely occurred solely among these women who could not work and therefore lost their welfare benefits.”

Related research: The Urban Institute crunches data and looks at welfare reform more than 15 years after it was enacted. A 2006 study by researchers at University of Santa Clara, “Leaving Welfare and Joining the Labor Force: Does Job Training Help? Evidence from an Innovative Intervention in New York City” looks at the effectiveness of a job-training program for welfare recipients in the early 1990s.

Keywords: poverty

Expert Commentary