The issue: Since the Occupy Wall Street movement took over New York’s Zuccotti Park in 2011, income inequality has become a major political issue in the United States. Less often discussed is the role labor unions play in protecting workers’ wages.

In America, according to an estimate from Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz, the top 1 percent of earners take home 25 percent of the nation’s income and control 40 percent of the wealth. Meanwhile, working-class wages have fallen over the past 40 years.

Membership in labor unions peaked in 1954 with 34.8 percent of workers, according to the Congressional Research Service, and has fallen since. In 2015, 11.1 percent of American workers were members of a union, according to U.S. Department of Labor statistics. And that year median wages for union members were about 26 percent higher.

Why has union membership fallen so dramatically? One reason is that America’s workforce has largely shifted from low-skill manufacturing jobs — which are largely homogenous and easy to organize — to jobs involving high-skilled tasks that require a college education, and which are often more individualized. Moreover, with globalization and the outsourcing of jobs, American workers and the U.S. economy have been forced to compete against other countries where labor is often cheaper. Unions, by offering members higher wages, push up the cost of production and make it harder for American firms to compete.

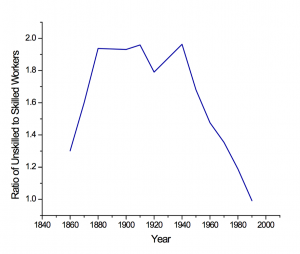

Add factory automation and the “demand for unskilled labor fell relative to the demand for skilled labor,” researchers at the Center for Economic Studies of the Census Bureau explained in a 2012 report. The Bureau defines unskilled workers “as clerical workers, laborers, operatives, and sales personnel, while skilled ones are taken to be craftsmen, managers, and professionals” (see chart to the left).

An academic study worth reading: “Unions and Income Inequality: A Panel Cointegration and Causality Analysis for the United States,” published in Economic Development Quarterly, July 2016.

Study summary: Unions have been shown to increase members’ wages. As a result, firms with large union membership among their workers have less money available to hire new workers, possibly increasing unemployment. Thus, many economists believe the net effect of unions on the distribution of income is unclear. But as unions recede, other trends are becoming apparent.

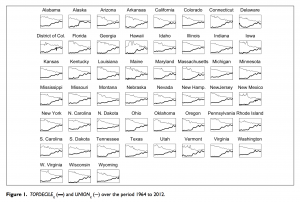

Dierk Herzer of Helmut-Schmidt-University in Hamburg, Germany examined the relationship between union membership and income inequality. He looks at two figures: The income share of the top 10 percent of earners in each U.S. state over the years 1964-2012, to measure inequality, and the rate of union membership in each state. He controlled for state income trends and education levels.

Findings:

- In every state, the top 10 percent of earners gained control over a larger share of the wealth at the same time union membership declined. (See figure.)

- There is a causal relationship between the density of union membership and income inequality over the long run. A 1 percent increase in union membership reduces the income share to the top 10 percent by 0.000514 percentage points. Given the average annual decline in union membership, that translates into the wealthiest 10 percent receiving an increase in income share of 0.00016 percent per year.

- The overall decline in union membership is responsible for about 5 percent of the increase in the income share of the top 10 percent.

- There is no evidence that income inequality led workers to leave unions. Moreover, a decrease in inequality does not boost union membership (even if it does hurt the wealth of the top 10 percent).

Other resources:

- The Bureau of Labor Statistics, part of the U.S. Department of Labor, publishes data on union membership and employment rates across the country. Some figures from 2015: New York State had the highest union membership rate in the country at 24.7 percent; South Carolina had the lowest at 2.1 percent. Men were more likely to be members than women (11.5 percent compared to 10.6 percent); Black workers were more likely to be members than White, Asian or Hispanic workers. Public-sector workers were five-times more likely to be union members than private-sector workers.

- The International Labor Organization (ILO) is a United Nations agency that brings together governments, employers and workers to set standards and develop policies on workers’ rights and work conditions. The ILO database has figures on topics such as migrant workers, child labor, grey economies and workers’ skills.

- The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) is a club of mostly rich countries that researches policy to help “governments foster prosperity and fight poverty through economic growth and financial stability.” It has published methods on how it measures inequality.

- Cornell University Library hosts a vast archive of information about labor unions and organizing, including a list of labor unions, bargaining language and labor history.

- The UC Berkeley Labor Center educates future labor leaders and carries out research on policy related to labor unions.

- The Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Labor Studies looks at labor unions in The Netherlands and Europe.

- The Heritage Foundation, a conservative Washington D.C. think-tank, argues that labor unions hurt consumers and the economy overall.

- Oxfam International, a confederation of anti-poverty groups, addressed income inequality in its 2014 briefing, “Working for the Few.”

- An October 2013 report from Credit Suisse, a bank, indicates that almost half of all wealth globally is owned by 1 percent of the population; 10 percent of the planet’s population owns 86 percent of its wealth.

Other research:

- University of California, Berkeley economist David Card estimated in 1998 that the decline in union membership caused between 10 percent and 20 percent of the rise in male income inequality over the previous 25 years.

- Celebrated French economist Thomas Piketty has collected accolades and criticism for his bestselling 2013 book on global inequality, Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

Keywords: labor unions, inequality, income inequality, economy, workforce, right-to-work, union pay

Expert Commentary