Mike Reilley is a veteran journalist and educator whose work has focused on bridging the traditional and digital media worlds, as well as curating online resources for deeper research. A former reporter and editor at the Los Angeles Times and a founding member of ChicagoTribune.com, he also started the widely used site Journalist’s Toolbox (Twitter: @journotoolbox), which he still actively updates for the Society of Professional Journalists. The site was developed out of his teaching at Northwestern University more than a decade ago. Reilley now teaches journalism at DePaul University’s College of Communication, where he helped launch the Chicago-based hyperlocal news site “The Red Line Project.”

As part of our “research chat” interview series, Journalist’s Resource caught up with Reilley at the 2012 AEJMC in Chicago. The following is an edited transcript:

______

Journalist’s Resource: Journalist’s Toolbox has been around a long time, but for those who may not be familiar, remind us what it offers. Why should every journalist — particularly young journalists — bookmark it?

Mike Reilley: One of the things that we discovered about Journalist’s Toolbox when we started it was that it was really helpful for those who are new to a newsroom and for those who may not have the resources and contacts built up that more veteran reporters might have. Or maybe a smaller newspaper or media outlet that doesn’t have a strong intranet of resources to go to. We’ve found it’s very popular among news librarians who wanted to do quick research. For reporters who are new to a beat, it can be very helpful. So, for example, someone who is going from a general assignment position to the science or education or city government beat. Our tools are organized much like beats in a newsroom. It can be very, very helpful to them. We try to dig a little deeper than what you might find on your typical search engine two or three pages down, and give people a little deeper content from sites.

JR: Can you give us some examples of news topics and the types of related resources?

Mike Reilley: I’ll talk about a few of the most popular ones. For example, with the elections and the party conventions, reporters can find links to various websites that track polls, historical sites about past national conventions, a whole section on political ad campaigns over the years and archives of old videos from that. If you’re researching the 10th anniversary of 9/11, a year ago, people were going into those pages we built 10 years earlier and going back to use as research. So it’s become very nice for archival purposes, but also for breaking news, too. Resources about the drought this summer have been very popular. It’s kept a lot of people coming to the public safety pages and our weather pages, where people have also been coming for hurricane-related resources. We try to build and tailor some of the content for breaking news stories, either planned or unplanned, but also to just have that depth of material there for ongoing stories. Sometimes it’s just as simple as having a page about something like sports law; that page has gotten a lot of traffic from sports reporters. Lord only knows that professional and college sports have given us a lot to write about there. So there’s a lot of ways the site can be used both on breaking news and more, in-depth investigative stories.

Mike Reilley: I’ll talk about a few of the most popular ones. For example, with the elections and the party conventions, reporters can find links to various websites that track polls, historical sites about past national conventions, a whole section on political ad campaigns over the years and archives of old videos from that. If you’re researching the 10th anniversary of 9/11, a year ago, people were going into those pages we built 10 years earlier and going back to use as research. So it’s become very nice for archival purposes, but also for breaking news, too. Resources about the drought this summer have been very popular. It’s kept a lot of people coming to the public safety pages and our weather pages, where people have also been coming for hurricane-related resources. We try to build and tailor some of the content for breaking news stories, either planned or unplanned, but also to just have that depth of material there for ongoing stories. Sometimes it’s just as simple as having a page about something like sports law; that page has gotten a lot of traffic from sports reporters. Lord only knows that professional and college sports have given us a lot to write about there. So there’s a lot of ways the site can be used both on breaking news and more, in-depth investigative stories.

Our resources on public records are second to none. We’ve got all sorts of resources on the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA); we’ve got all kinds of different public records databases — some free, some you have to pay a small fee for. But it’s very helpful to a blogger or maybe someone in a smaller newsroom who needs to be able to crack open and find public records very quickly and who might not have time to go down to city hall and get them or file a FOIA request. Some of this stuff you can access through databases.

JR: It seems at times that Google might be better off just taking your first 20 links or so as search results on certain key words — that human curation can sometimes be better for finding in-depth, research-oriented resources.

Mike Reilley: We built the site with kind of a Delicious-like presentation. We wanted to give people a really good, quick snapshot of what they needed to know about that specific topic or that specific beat. But I have to give Google a lot of credit. We grew hand-in-hand as Google was growing. Because a lot of people who were linking to us were news librarians and academics, Google’s algorithm moved us up very high in search engine rankings, particularly for searches on “journalism” or “journalist” or “journalism tools.” This was in the Wild West of the Internet — 2001, 2002 — and we saw a lot of organic traffic.

JR: Let’s talk about your teaching and academic work, and how it all lines up with your interest in curating information resources. When you teach your online and beat reporting classes, what are some of the information-seeking tips you give students?

Mike Reilley: I always couch my advice about the Internet this way to my students: It’s one more tool in your arsenal in the reporting field. It’s not the end-all, be-all. It’s not going to write your story for you. You can’t use it as your sole reporting source. Nearly every assignment I give out requires them to do field reporting. Now it can help them background the piece and give them some quick information at their fingertips, but it doesn’t necessarily give them all the answers.

I talk to them a lot about the power of the link. I give a little talk called “thinking before linking,” and we talk about how when we write our stories and link off to somewhere for background, we want to be asking, “Is that the best, more credible source I can find? Can I find something better?” I have the “Wikipedia rule,” which a lot of journalism professors have. Wikipedia is off limits as your main source but you can use the citations at the bottom of the page. They can be very, very helpful in sourcing and back-grounding before you go out.

I also encourage students to go to the library. Here at the DePaul campus, we have a nice library, but we’re also right across the street from the Harold Washington Library. I have them take a look at Lexis-Nexis and all of the other materials that you have at your fingertips that are available in a library; many times those are underutilized in newsrooms. I’ll send them to the Toolbox a little bit, but I’ll also send them some social media, as well, to help create crowdsourcing techniques. I came up in the old-school, school-leather reporting days, when we didn’t have the Internet at our fingertips. We relied on news librarians and our research — and at times, unfortunately, even our own memory!

We’re so fortunate today to have all of this research right here at our fingertips. But we also have to be very, very careful that we’re picking the right information, and that it’s correct, and not the first information you find in somebody’s fan blog or a bad statistic. We go through a checklist of things on verifying tweets, on verifying information on a site, credibility. I show them how to look up a Web address and see who owns it, at Whois.net. Is this website really an environmental advocacy website, or is it a petroleum-funded site, a front controlled by an oil company? There’s a difference between these two. I try to get the students to ask, “Have I exhausted all options to try to get the best source?”

JR: How did “The Red Line Project” website come about? What role is it playing in the Chicago community now?

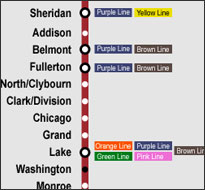

Mike Reilley: I ride the Red Line to and from work most days every week. I live near Wrigley Field. My job is in the South Loop in Chicago, and so I ride the elevated train for about six stops and then go into the subway. Riding an elevated train gives you an unique perspective on the city: You can look down into the neighborhoods and see what’s going on. You can be riding and see flashing lights and say, “Hey, what’s going with that ambulance and fire truck?” You always have this neat perspective. The Red Line runs north-south, from the border of Evanston through the city of Chicago, down to the South Side of Chicago on 95th Street. It’s one of the main arteries that connect the city together, along with the Blue Line. I thought to myself, “What a great way to tie the city together, and just sort of lay out a news page.” There’s a lot happening in these neighborhoods. Some are very urban, and some are a little more suburban — a lower-key lifestyle. But much of the city’s happenings take place within a mile of the Red Line. There’s a lot going on in those areas and neighborhoods.

Mike Reilley: I ride the Red Line to and from work most days every week. I live near Wrigley Field. My job is in the South Loop in Chicago, and so I ride the elevated train for about six stops and then go into the subway. Riding an elevated train gives you an unique perspective on the city: You can look down into the neighborhoods and see what’s going on. You can be riding and see flashing lights and say, “Hey, what’s going with that ambulance and fire truck?” You always have this neat perspective. The Red Line runs north-south, from the border of Evanston through the city of Chicago, down to the South Side of Chicago on 95th Street. It’s one of the main arteries that connect the city together, along with the Blue Line. I thought to myself, “What a great way to tie the city together, and just sort of lay out a news page.” There’s a lot happening in these neighborhoods. Some are very urban, and some are a little more suburban — a lower-key lifestyle. But much of the city’s happenings take place within a mile of the Red Line. There’s a lot going on in those areas and neighborhoods.

I always use an Internet analogy when explaining the city dynamics to students: The Internet is the railroad, and the Web is the content. Likewise, with the Red Line Project, we’re going to use the train tracks are the way to package our content about the city of Chicago. We try to cover stories in various neighborhoods that maybe don’t get covered by the Chicago Tribune or the Chicago Sun-Times. We also try to look for trends — for example, business along the Red Line. We put together a small business package, with students interviewing various small business owners along the Red Line and looking at how they’ve been faring during the Recession — and even how the closing of some Red Line stops was affecting their business. It was really good reporting. So we try to cover things that the main newspapers don’t have the resources to cover anymore or issues that are just not their main area of focus.

JR: You came up in the traditional media world, but then adapted and helped make the transition to the digital with the ChicagoTribune.com and more. Now you’re teaching this convergence to the next generation of journalists. How do you see the future of journalism?

JR: You came up in the traditional media world, but then adapted and helped make the transition to the digital with the ChicagoTribune.com and more. Now you’re teaching this convergence to the next generation of journalists. How do you see the future of journalism?

Mike Reilley: It’s such an exciting time to be part of journalism and journalism education. Just in the last four or five years there’s been tremendous change. Unfortunately, a by-product of that change has been the layoffs, and a lot of great people — people who were mentors to me — who are unemployed. That’s really hard to swallow. I really miss the days of the 1980s and early 1990s when we had a couple deadlines and we cranked out stories for a newspaper. I loved it. I miss it dearly. But I understand we have to change and perish in this business. And we have all sorts of tools now. I began to see this coming around 1995, when I was in graduate school at Northwestern. The new tools, and the new platforms on which we have to tell stories, opens up new possibilities. The one concern I have — while I love apps and all the tools we have in this industry — I hope we don’t lose that basic storytelling approach. This was borne out of my print journalism years. That’s why I always make sure my students do shoe-leather reporting in my classes — that they interview people face-to-face and package that with digital elements, whether it be maps, graphs, photos. We still have to have storytelling as the core of what we do as journalists. If we lose that, we’re in big, big trouble. The business models have fallen by the wayside, but given what we’re creating and introducing now online through various apps and bold platforms, I think there is no more interesting time to be in this industry.

Tags: research chat, training

Expert Commentary