Editor’s note: On March 12, the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy will award the 2019 Goldsmith Prize for Investigative Reporting to a stellar investigative report that has had a direct impact on government, politics and policy at the national, state or local levels. Seven reporting teams have been chosen as finalists for the 2019 prize, which carries a $10,000 award for finalists and $25,000 for the winner. This year, for the first time, Journalist’s Resource is publishing a series of interviews with the finalists, in the interest of giving a behind-the-scenes explanation of the process, tools, and legwork it takes to create an important piece of investigative journalism. Journalist’s Resource is a project of the Shorenstein Center, but had no involvement with or influence on the judging process for the Goldsmith Prize finalists or winner.

————–

Reporters at The Philadelphia Inquirer found over 9,000 environmental problems in the city’s public schools, including mold, asbestos and lead paint, during a nine month investigation that relied on community-based testing.

The series, called “Toxic City: Sick Schools,” was part of a broader investigative series, “Toxic City,” that looks at environmental hazards in Philadelphia. The paper already had looked at lead paint in homes and lead levels in soil before shifting its focus to schools. Journalist’s Resource talked to several reporters who worked on the project to learn more about the work behind it.

“Every child in Philadelphia has to go to school, spends more hours during the year in school than at home, and we knew that the schools were very old,” reporter Barbara Laker explained. “The average age [of Philadelphia public school buildings] is like 70 years and we knew they had lead dust and asbestos, and, in some cases, lead in the water and mold.”

The journalists wanted to conduct independent environmental testing to investigate the extent of these hazards in the district. But there was a major obstacle: access.

“One of the huge hurdles we had was that we didn’t have access to public schools,” reporter Wendy Ruderman said. School security is strict, and the reporters did not want to trespass in order to collect the dust and water samples.

“So we came up with the idea to enlist staffers within schools to do environmental testing for us,” Ruderman explained. “It was extremely difficult, because many of the people we approached — the teachers, the staffers — were very afraid for their jobs, very afraid of retribution … if they got caught doing this testing.”

And yet, Ruderman and Laker were able to convince dozens of school employees to execute the testing. This is the story of how they persuaded teachers and staffers to assist with the investigation, and the steps involved in developing the testing protocol and training the volunteers to execute it.

THE PROTOCOL

To develop the testing protocol, Ruderman and Laker went to a certified lab where they received training for dust-wipe testing for each of the hazards they were interested in. “They illustrated it for us, and then we had to do it in front of them so they could see that we knew how to do it,” Laker explained.

Laker and Ruderman created detailed instructions for testing for each hazard. Ruderman said her colleagues served as guinea pigs for the draft protocols: “We passed the instructions around, just to various people in the office, to see if the instructions were understandable.”

The team let their reporting guide their testing strategy, according to Ruderman. At first they relied on internal school records, such as maintenance documents, and public documents, such as asbestos reports published by the school district and the public health department.

Reporter Dylan Purcell analyzed all of the data and created a database with details down to the classroom level of hazards in the district’s public schools. (The team later made this information public through an interactive tool called School Checkup, designed by Garland Potts, who creates data visualizations for the Inquirer.)

“We started with a study of the buildings that was done by a contractor that was helpful but not perfect,” Purcell explained. Adding in data from other reports, Purcell could pinpoint areas to focus volunteer recruitment and testing efforts.

“We decided to look at at least five years’ worth of data on all of these different environmental factors, and it turned out to be about a dozen data sets that guided us along the way,” Purcell added. “I wanted to understand each school building and know it as intimately as I could get through data. So I was layering datasets together a lot of times in SQL Server, just so I could, at a glance, pull up a building and say, ‘Okay, it’s got these five problems, like, it’s notoriously bad for asbestos damage, or it’s got flaking lead paint through 70 percent of the building.’”

To recruit testers, Laker and Ruderman went to community meetings with teachers in attendance, such as union meetings. They contacted teachers and other school employees through social media; they made connections through word-of-mouth; and they also made calls to teachers’ homes, relying on phone numbers connected to public lists of teacher salaries.

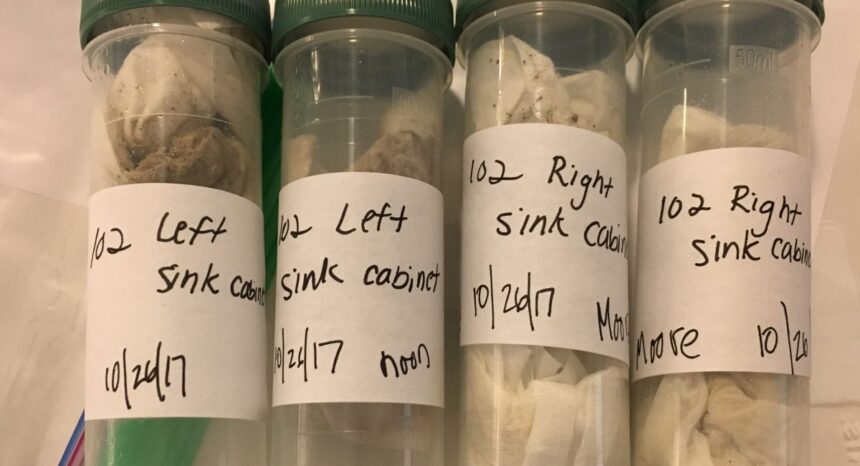

“I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say we gave out hundreds of testing kits with instructions and vials,” Ruderman said. “In the end, we got teachers and staffers — about 26 of them — who were really fantastic.”

Their recruitment efforts were most successful with employees who understood the stakes of the effort. “The teachers who were most willing to help us were those that were really concerned about the conditions in the schools themselves,” Laker said. “These are teachers who came into their classroom and had to scoop up mice droppings before they started class. They saw all this — what looked like lead dust — all over the windowsills and the floors in kindergarten rooms and first grade rooms. And they could see holes in the ceiling, with the ceiling falling down. They could see mold all over the walls and floors and other conditions like broken toilets.”

Laker continued, “These were very conscientious teachers and staffers who really cared about the school and cared about their children in the classrooms and wanted to do something to expose this and help and confirm what their fears were.”

Ruderman and Laker trained the testers individually in off-site locations, including parked cars and cafes. “In addition to giving the teachers instructions, we had to sit down and then train them,” Ruderman explained. “We would go over the instructions, take out a moist wipe that you use to collect the sample, show them how to do it and then make sure that they understood how to do it.”

Testing locations were determined through Purcell’s data analysis as well as employees’ insights. Laker said testers would sometimes collect samples at early hours in the morning, before students had arrived, in order to avoid being seen.

When the teachers and staffers collected the samples, they also took photos of themselves doing the testing or of the location they tested. Then Laker and Ruderman met with them again, to go over how they collected the sample and verify that they had followed the protocol.

THE RESULTS

Once the results started coming in, the team felt compelled to share the information with district officials about the hazards they had discovered, despite the investigation’s ongoing status. “A lot of teachers put themselves at risk to help us do this testing, and the results were extremely disturbing and unsettling — so much so that in the midst of the project, months before we published, we would tell the school district what the results were,” Ruderman said. “Our editors had decided from the beginning that the most important thing was to help the people in the building — the students and the teachers and staff — so we would alert the school district to high test results as we went along, way before the project was ready to be published.”

It was a risky move. “When we did tell them early on some of the test results, they did start to try to figure out who was doing the testing,” Ruderman said. “We were worried about a chilling effect, but we did let the school district know that we were hearing through our teachers and our sources on the ground that they were trying to figure out who did the testing and that they wanted to stop it. And they did tell teachers not to cooperate with us. And we let them [school district officials] know that we were hearing that, with the suggestion that if that were the case, we would be interested in writing something.”

The district also took issue with the Inquirer’s testing method, arguing that air monitoring for asbestos is more accurate than dust wipes. The paper dedicated space in a story to the district’s complaints.

“To be completely aboveboard, we put their total stance, their whole position, not only in the story, but then did a sidebar that described in detail how we did the testing,” Ruderman said. “So the public could see for themselves how we did it. And we said up front, yeah, most people test air samples and not dust wipe samples, but we did get several experts to weigh in and actually endorse the way we did the testing, saying it was a really good investigative tool that indicated there was a real problem there.”

School employees also helped the team photograph the story. “It’s really hard to report about invisible hazards, or health hazards, things that you can’t see, and tell a story visually,” Ruderman noted. But because the team had sources inside the schools, they received valuable tips they could pass on to their photographer, Jessica Griffin.

“One of the stories was about how the school district would do construction during school hours and put kids at risk,” Ruderman said. “They were doing this work not only during school hours, but without any dust control measures. And so the teacher would call me and she was saying, ‘They’re out here doing the work right now and there’s stuff everywhere,’ and then I would be able to call Jessica … in that way a lot of the reporting was unassailable because of the fact that Jessica could run to different places” and get photographs and video.

Adding the voices of those affected by these hazards also offered a compelling, human illustration of the problem. But again, finding sources wasn’t easy.

At first, all they had “was a source who told us that he knew that a first-grade child had been severely lead poisoned,” Laker said. “He gave me the name of the school, and that’s all.”

Laker began her search with that bit of information. “I went to the school several afternoons and hung out outside the school and tried to talk to every parent who looked like they had a first-grader with them,” she said. “Eventually I found some parents who said they would help me.” She found out the child’s name — Dean Pagan — and then tracked down the family. At first they were hesitant to talk, but eventually agreed.

“They wanted people to know that as much as they can take care of their child at home, parents have to be aware that their child can be harmed at school if they’re exposed to these environmental hazards,” Laker said. “I think they were also kind of mad at the district and the way the district downplayed it. But their main focus and their main drive was to help other kids and not have another Dean or not see another child lead poisoned in the school.”

For journalists interested in reporting on environmental hazards in their local school district, Purcell stressed the following fundamentals:

- Across the country, all public and non-profit schools are required to do asbestos testing every three years and make the results publicly available.

- If a school building was built before 1978, there’s a high likelihood it might have lead paint inside.

- If a school building was built before 1980, it could contain asbestos.

- Consider asking about the following: When was the water last tested in the district? If the district is building a school on a new site, has the ground been tested? Is it a former toxic site?

And if you’d like to model a testing protocol after the Inquirer’s, you can read their lead and asbestos sampling instructions.

Check out all of our coverage of the 2019 Goldsmith Finalists, including an account of how one reporter investigated an Alabama sheriff who pocketed over $2 million in jail food funds, how two journalists’ tenacity, language skills and cultural competency helped them investigate a teen labor trafficking scheme in Ohio, how public records helped reporters investigate police abuse of power and how ProPublica helped to shape national immigration policy through their investigation of children’s shelters.

Expert Commentary