Annually, the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy awards the Goldsmith Prize for Investigative Reporting to a stellar investigative report that has had a direct impact on government, politics and policy at the national, state or local levels. Six reporting teams were chosen as finalists for the 2020 prize, which carries a $10,000 award for finalists and $25,000 for the winner. This year, as we did last year, Journalist’s Resource is publishing a series of interviews with the finalists, in the interest of giving a behind-the-scenes explanation of the process, tools, and legwork it takes to create an important piece of investigative journalism. Journalist’s Resource is a project of the Shorenstein Center, but was not involved in the judging process for the Goldsmith Prize finalists or winner. “Copy, Paste, Legislate” — a collaboration among The Arizona Republic, USA TODAY and the Center for Public Integrity — was named the winner on March 23.

On Dec. 9, 2019, The Washington Post published a series of articles on the Afghanistan Papers, a previously secret trove of candid interviews with top military and government officials from the Afghanistan War, uncovered by investigative reporter Craig Whitlock. The interviews shed unprecedented light on fundamental missteps and false public statements that officials deliberately made during the war, ongoing since 2001.

“It was one of those things that really hit a chord,” Whitlock says. “People really stayed with it. They have a hunger for this type of journalism.”

More than three years before the series went live, Whitlock, a veteran Post journalist who has reported from more than 60 countries, got a tip. Michael Flynn, who would become President Donald Trump’s short-lived national security advisor and later pleaded guilty to a felony, had given “a blistering interview to an obscure government agency about Afghanistan,” Whitlock recalls.

The tip came in August 2016. Flynn, a retired U.S. Army lieutenant general, was receiving national media attention for his support of then-candidate Trump. A few weeks before the tip, at the Republican National Convention in Cleveland, Flynn had egged on a crowd of thousands with chants of “lock her up” — encouraging the imprisonment of rival presidential candidate Hillary Clinton over her use of a private email server while serving as secretary of state. Flynn had also led wartime intelligence efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan under presidents George H. Bush and Barack Obama.

“We had been focusing on Flynn quite a bit,” Whitlock says. “Even though he was well known in national security circles, he was just getting known in political circles.”

FOIA fight

Whitlock knew that officials from the office of the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction were the ones who had interviewed Flynn. On Aug. 24, 2016, Whitlock filed a Freedom of Information Act request with SIGAR for transcripts and recordings of the Flynn interview.

“We thought it would be a straightforward records request,” Whitlock says. “The inspector general said, ‘Sure, give us a few days.’ That stretched to a few weeks. By the time Flynn got appointed [national security] advisor, the inspector general summarily denied the request — and we had heard there were hundreds of other interviews done.”

Whitlock filed another FOIA request in March 2017 for the other SIGAR interviews.

“The Post thought there was an extreme public interest in seeing what top generals thought about what was going on in Afghanistan,” Whitlock recalls.

Whitlock, his editors and Post lawyers decided to go to court to pry the records loose.

“It’s a big step to file a FOIA lawsuit,” says Whitlock. But the lawyers thought he had a strong case.

The Post team had to weigh whether to sue for all the interview records or just Flynn’s. They decided to focus on Flynn’s interviews, as a test case.

More than a year after Whitlock filed the original FOIA, the Post filed suit in U.S. District Court in Washington D.C. SIGAR waved the white flag about three months later, without a judge’s ruling, and released the Flynn interview materials.

Reporting tip: Don’t give up — follow up.

Especially when it comes to FOIA requests, a closed door is sometimes just a door that hasn’t opened yet. “If you stick with it and you’re patient and keep prodding and trying to hold the agency accountable to the law, our story shows you can get somewhere,” Whitlock says.

The Flynn interview, conducted Nov. 10, 2015, was eye-popping in its candor.

“The policy decisions and the operational decisions, I don’t think matched what the intelligence was saying,” Flynn told SIGAR interviewers at one point.

“Operational commanders, State Department policymakers, and Department of Defense policymakers are going to be inherently rosy in their assessments,” Flynn said, according to the transcripts. “They will be unaccepting of hard hitting intelligence.”

And then: “From ambassadors down to the low level, [they all say] we are doing a great job. Really? So if we are doing such a great job, why does it feel like we’re losing?”

SIGAR responded to the FOIA request for the remaining interviews with what Whitlock calls a “rope-a-dope” approach. Agency staff said it would take time. The materials would need to be vetted for sensitive information. Interviews were released in dribs and drabs.

“It was delay, delay, delay,” Whitlock says.

The Post sued for the rest of the interviews in November 2018. “A partial government shutdown in early 2019 led to more delays,” Whitlock explained in a Post article. Finally, in August 2019, the agency sent the Post the final batch of a trove of documents that were the backbone of the investigation.

“There is a fine line between spin and just not telling the truth, and intentionally spinning stuff to be false,” Whitlock says. “These documents show they went past that line many times.”

Still, 300 names were redacted of the roughly 400 people interviewed. Whitlock thinks there are other SIGAR interviews still out there. He says the Post has been waiting since September 2019 for a ruling in another case, which could force the agency to release more names, from District Judge Amy Berman Jackson. She’s the same judge Trump has publicly criticized for rulings related to his friend Roger Stone’s conviction for lying under oath to Congress.

Something for the rest of the newsrooms out there

Most newsrooms don’t have the lawyerly resources the Post can boast. Still, “it isn’t like we have unlimited resources,” Whitlock says. He was able to spend most of 2019 tracking down the Afghanistan Papers. But there was no phalanx of reporters on the story.

“It was me and my assignment editor on it,” Whitlock says.

Reporting tip: Beef up your FOIA side hustle.

Reporting on a single beat is hard enough, let alone the multiple beats that reporters often have to cover in an era of downsized newsrooms. Still, Whitlock notes that this story came about because of a tip and a FOIA that weren’t part of a story he was actively pursuing. “You stick with it and juggle it,” he says. “It’s no different here than anywhere else.”

Regional papers can often turn to pro-bono legal help for FOIA requests. The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press offers a legal defense and FOIA hotline. The Free Expression Legal Network, made up of law school clinics and legal academics, is another good place to start. Some lawyers will take cases on contingency, and only get paid if a judge orders the government to pay legal fees.

“There’s options out there,” Whitlock says. “You don’t have to hire a blue chip law firm.”

Sifting through — and organizing — a trove

With SIGAR interviews in hand, the real fun began: Whitlock had to read through 2,000 pages of transcripts for newsworthy nuggets that, together, would create a cohesive narrative.

“There’s a challenge of, ‘What does this all add up to?’” Whitlock says. “What do you write out of it? That took many months to find.”

Reporting tip: There’s no guidebook for sifting through a massive trove of documents.

But themes will emerge with time. “There were several patterns,” says Whitlock. “The strategy of the war was a mess. The government wasn’t truthful. Some clear themes of corruption and the heroin production epidemic in Afghanistan. Problems training the Afghan army. So there were some things we put our fingers on early on. We just kept sifting and mining.”

Organizing the transcripts, patterns and Whitlock’s own thoughts were beyond the capabilities of the tools journalists usually use for data analysis.

“It’s not something you can put in a spreadsheet,” Whitlock says. “These are interviews.”

Reporting tip: Think outside the journalism toolbox.

Whitlock turned to a case management software program called CaseFleet. “Lawyers use it,” he says. “Lawyers get some big class action lawsuit with lots and lots of documents. You’re trying to organize it by facts and dates and people. So the Post got a subscription to it — I don’t think it’s that much. It’s an 18-year war to keep track of. I can’t remember who was the general in 2002 and what happened on this date in 2009. This was a great way to do that.”

Telling the story, completely

Production and presentation posed another set of challenges. Post editors wanted to publish all the documents. They wanted to provide access without bogging down readers.

“We spent all of 2019 in really intensive discussions with talented people in the newsroom who do database work and graphic design and audio and video,” Whitlock says. “How do we use these tools to our advantage? How do we tell these stories in a more effective way?”

Reporting tip: Bring visual thinkers in early.

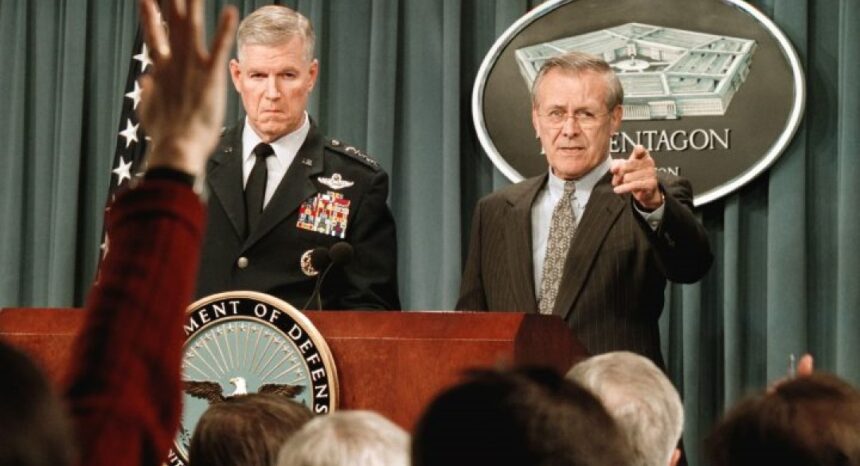

The photographs included in the final package are striking. There are wounded American soldiers, warlords and coalition forces and massive refugee camps. The images drive home the stakes of Whitlock’s reporting — that a nearly two-decade war, which top U.S. officials have had serious doubts about all along, has had devastating personal consequences. Whitlock looped in a Post photo editor on early story drafts. The photo editor had 50,000 images to choose from — to match to Whitlock’s text. The photo editor intimately understood the reporting. “In one story, the lede was about corruption, about dark money flooding Afghanistan,” says Whitlock. “He finds a photo of a money changer in Afghanistan with stacks and stacks of dirty money that hasn’t been laundered yet. It was a perfect image.”

Sniffing out a ‘media hound’

John Sopko runs SIGAR, the agency that did the Flynn and other interviews.

“He’s known as a media hound,” Whitlock says. “He’s not the usual bureaucrat who hates reporters. In his office in northern Virginia there are press clippings all over the wall. He’s clearly a guy who loves to be interviewed.”

When it was apparent the Post was going to win its second FOIA suit, SIGAR sent word that other agencies would have to review the documents before they were released — even though Sopko’s agency doesn’t have the authority to classify, according to Whitlock.

“That was my biggest surprise, was how hard they fought it even though it was of extraordinary value,” he says. “Still can’t get my head around why he did that.”

Expert Commentary