American patients in the rural South are more likely to receive opioid prescriptions than patients in the urban North, according to two new studies from Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania.

In one new analysis of data from 2016, researchers found that opioid prescribing rates per 100 people vary across congressional districts, from a high of 166 in Alabama’s Fourth Congressional District to a low of 23 in New York’s Ninth Congressional District. It’s important to note these rates can include multiple prescriptions written for one individual.

According to their analysis, the areas with the highest opioid prescribing rates are in the South, Appalachia and the rural West. The districts with the lowest prescribing rates are located in New York City and urban areas in California and Virginia.

A full ranking of all congressional districts is available as a supplemental table to the paper.

The researchers had legislators in mind when they chose to study prescribing rates by congressional district rather than by county or state. The paper, published in the American Journal of Public Health, indicates that analysis at the congressional district level might facilitate targeted policy interventions.

“We are interested in congressional districts because they have a certain level of political accountability, they have an elected representative, in the way that counties do not,” said Jack Cordes, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and an author on the paper, in a phone interview. The data he and his co-authors collected, he continued, “makes it easier for representatives to understand what their particular constituents are going through, and it makes it easier for advocacy — for certain interventions and polices.”

Moreover, analysis of prescribing rates at the congressional district level might reveal trends that aren’t evident at the state level, the paper notes. For example, Virginia is noteworthy in that it contains districts in both the top and bottom 10 for opioid prescribing rates; in the rural, western part of the state, opioid prescriptions are high, whereas in the metropolitan north of the state, near Washington D.C., rates are low.

To create the map, the researchers looked at prescribing rates for opioids provided by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and population data collected by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Cordes noted that while the findings reveal important geographical trends in the prescribing rates of opioids, the results don’t reveal whether the patients actually use these prescriptions, or whether they are tied to overdoses or deaths.

“These are areas that we identified as [being] at higher risk because of oversaturation of opioids, but it’s not a particular health outcome,” he told Journalist’s Resource.

A new paper in Annals of Emergency Medicine offers further detail on similar trends, presenting links between receiving opioid prescriptions for minor injuries and increased likelihood of prolonged use.

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania analyzed opioid prescribing rates among patients who showed up to the emergency room with ankle sprains between 2011 and 2015. The data was collected from a sample of privately insured people across the United States; this sample resembled the U.S. population of commercially insured people in terms of demographics. The sample included over 30,000 patients who had not received opioids in the six months prior to their E.R. visit.

“Ankle sprains are a minor, self-limited condition for which there is likely to be little clinical benefit from opioids,” the authors write. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are the recommended treatment for ankle sprains and are shown to be as effective as opioids in reducing pain.

Despite this, nearly 20 percent of the studied ankle sprain patients in 2015 received a prescription for opioids. While this was a decrease from the overall prescription rate in 2011 of 28 percent, more than 140,000 opioid tablets “could have been prevented from entering the community if opioids had not been prescribed for our study sample,” the authors write.

Patients with ankle sprains who received prescriptions for longer courses of opioids (more than 30 tablets) had a 6.3 percent likelihood of developing prolonged use, as compared to a 1.2 percent likelihood for those who received 10 tablets or less — a nearly five-fold increase.

Moreover, most of the patients who received subsequent prescriptions got them for reasons unrelated to sprains and strains or joint disorders.

“This suggests that association between larger prescriptions and increased likelihood of prolonged use could be due to other factors such as patients requesting opioids as default pain control, or the development of dependence or misuse,” the authors write.

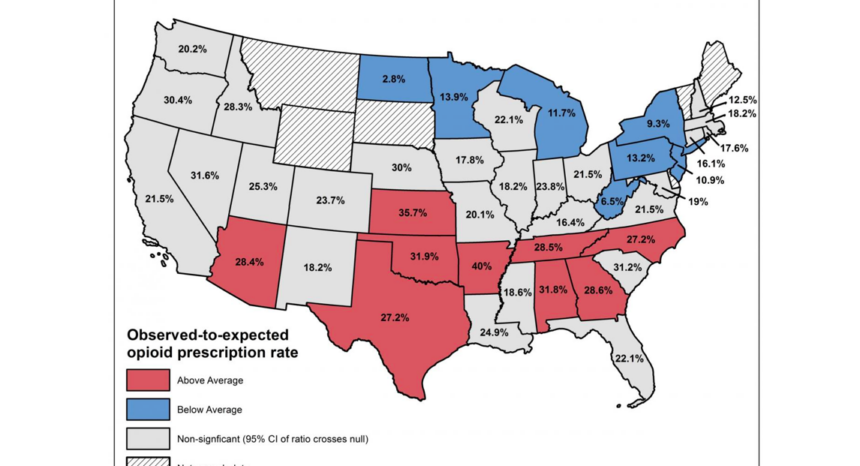

As with the congressional district analysis, certain geographical trends held. Prescribing rates varied drastically across the country, with above-average rates concentrated in the South and below-average rates in the North. North Dakota had the lowest prescribing rates: 2.8 percent of patients with sprained ankles received opioids. By contrast, in Arkansas, 40 percent of patients with sprained ankles were prescribed opioids. The authors indicate that their findings present “multiple opportunities for clinical, health system and state-level interventions.”

Journalist’s Resource has also covered research that shows how the race gap in prescription opioid use is narrowing and a paper that highlights how unlikely it is for opioid users referred for treatment by the criminal justice system to receive evidence-based treatments.

Expert Commentary