Forced, unpaid labor formed the stilts that propped up numerous aspects of early American industry. Newspapers were no exception. Slave owners paid newspapers to publish advertisements that described the physical traits of slaves who had run away, offering rewards for their return. Those ads “were a lucrative and consistent source of revenue” for newspaper printers, writes Jordan Taylor, visiting assistant history professor at Smith College, in a new paper published in the journal Early American Studies.

But colonial newspapers weren’t mere messengers for slavers. Taylor chronicles more than 2,100 unique ads from 1704 to 1807 that show newspaper publishers also acted as brokers, facilitating the buying and selling of up to 3,400 men, women and children as chattel. For most of that century or so, slave brokerage ads appeared primarily in Northern newspapers, Taylor finds in his paper, “Enquire of the Printer: Newspaper Advertising and the Moral Economy of the North American Slave Trade.”

“Newspaper editors and printers jumped enthusiastically into brokering the slave trade,” he says. “Journalists and members of the news media today should be reckoning with that.”

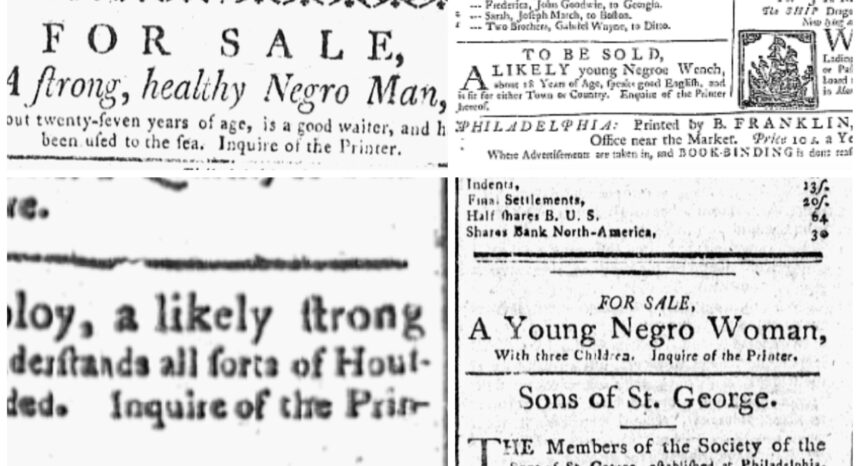

Ads were often formulaic and brusque, and most newspapers charged a flat rate for short ads. “For sale,” reads one ad Taylor found from 1792 in the Independent Gazetteer out of Philadelphia, “A Young Negro Woman, With three Children. Inquire of the Printer.” An interested buyer would go to the offices of the Gazetteer to find out how to reach the seller. Sometimes a printer would provide further details about the sale, such as price terms and attributes of the person or people being sold.

Ads were often formulaic and brusque, and most newspapers charged a flat rate for short ads. “For sale,” reads one ad Taylor found from 1792 in the Independent Gazetteer out of Philadelphia, “A Young Negro Woman, With three Children. Inquire of the Printer.” An interested buyer would go to the offices of the Gazetteer to find out how to reach the seller. Sometimes a printer would provide further details about the sale, such as price terms and attributes of the person or people being sold.

On the same broadsheet as that Gazetteer ad: Poems exalting freedom, offering sympathy to slaves. Today, those odes to egalitarianism appear undercut by the slave-for-sale ad — by the printer’s profit motive.

Threads through time: Journalism’s legacy of slave brokerage today

On Jan. 1, 1808, the federal government outlawed the transatlantic slave trade. Slave trading subsequently proliferated across state lines, rather than across national boundaries. Large numbers of slaves were moved from the North and upper South to the Deep South over the ensuing decades. The buying and selling of slaves evolved into a profession.

“The image of the auction block starts to pick up at that point,” Taylor says.

Slave brokers and traders were relatively common in slaveholding states during the run-up to the Civil War. By 1860, a quarter of households in the South held slaves. Northern states barred slavery around the turn of the century, but newspaper printers there had already helped establish America’s economy of bonded labor.

It’s important to note that because the North industrialized well before the South, it had many more newspapers during colonial times. And many of those Northern papers have been preserved, whereas “a lot of Southern newspapers don’t exist anymore,” Taylor says.

While the Independent Gazetteer and other newspapers that brokered slave sales folded decades before the Civil War, a handful of media outlets today can trace their histories to this legacy of slave brokerage. They include the Hartford Courant, The New Hampshire Gazette, the Poughkeepsie Journal, The Augusta Chronicle, The Post and Courier in Charleston, South Carolina and the New York Post, according to Taylor.

A century of slave brokerage

For most of the 1700s, slave-for-sale ads in which printers acted as brokers appeared primarily in states that would make up large swaths of the Union during the Civil War. New England newspapers — those in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut — peaked with 146 slave broker ads in the 1760s, according to Taylor’s analysis. Mid-Atlantic papers — those in Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey and Delaware — peaked at 198 slave broker ads in the 1790s.

There are fewer known instances of slave broker ads through most of the 1700s in the South and West — in Maryland, the District of Columbia, Virginia, South Carolina, Georgia, Kentucky and Tennessee — but ads peaked sharply in the late 1700s, Taylor finds. In the 1780s, 89 slave broker ads ran in newspapers in those states, which would later make up large parts of the Confederacy; then 228 ads in the 1790s; and 245 ads from 1800 to 1807.

Publish or perish

Newspapers in colonial America were often shoestring operations. A newly formed paper would likely be family run, sometimes with an apprentice. Newspapers were easy to start, Taylor explains, and quick to fail.

“One bad year and they would go belly up,” he says.

Colonial newspapers didn’t simply deliver news — they were marketplaces. They connected buyers and sellers of a range of goods and services. They centralized a decentralized world.

Imagine a farm selling butter. A potential customer with business in a nearby city might be more willing to travel to a newspaper office there to learn the terms of the butter sale, rather than to the farm miles outside the city. In addition to ad revenue, newspapers stood to profit when readers came through their offices. For the same reason museums direct visitors to exit through the gift shop, “printers thrived when their shops buzzed with attention,” Taylor writes. “A visitor inquiring about a slave sale in the print shop might offer news, share a letter, or even purchase an almanac.”

A slave-for-sale ad might cost several shillings. These ads were a non-trivial revenue stream for newspapers. Benjamin Franklin, one of the nation’s founding fathers and a vocal abolitionist in the twilight of his life, printed 277 slave-for-sale ads in his Pennsylvania Gazette over the course of 37 years in the mid-1700s, earning him a total of about 90 pounds, Taylor estimates. That’s roughly half of what Franklin paid to buy the paper in 1729. The printer — Franklin — was listed as the slave-sale broker in 113 ads, Taylor finds.

“Franklin’s newspaper was unusually profitable,” he writes, but prominent and less-prominent printers alike acted as slave-sale brokers for the simple reason that doing so helped maintain their livelihoods.

While journalism’s profit motive remains strong among major media outlets, the industry has changed substantially since the colonial era. Objectivity as a guiding principle was, by and large, unheard of in colonial media. Most news outlets now retain strong barriers between their editorial and business shops.

Still, the image of the objective, critical journalist — cultivated by white men who historically dominated the field — is a modern phenomenon.

“There was a moment in the early-to-mid 20th century when journalists were able to project themselves as people standing apart from the marketplace,” Taylor says. “That was an aberration in the larger sweep of American history.”

For more research on racism’s indelible imprint, learn how 1930s housing practices eroded black wealth, why higher taxes meant more violence against Black politicians during Reconstruction and what Khalil Gibran Muhammad has to say on calling racism what it is.

Expert Commentary