On September 30, 2015, the U.S. Federal Court of Appeals overruled a lower court’s decision that colleges and universities could pay student athletes up to $5,000 in deferred compensation, which would be held in a trust until the athletes leave college. This decision was a win for the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA), which claims that the amateur nature of college sports should keep it exempt from antitrust laws, or laws put in place to ensure fair and free competition in an open marketplace. The original class action lawsuit, O’Bannon v. NCAA, involved a lead plaintiff, former UCLA basketball player, Ed O’Bannon, who claimed that athletes should be allowed earnings from the marketing and commercialization of their images and likenesses after they leave college.

The 2014 ruling in that case was made by Judge Claudia Wilken, who maintained that the NCAA was in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Laws. The decision to reverse that ruling by the U.S. Federal Court of Appeals in 2015 comes on the heels of another case involving college athletes and whether or not they are entitled to compensation. In April 2015, Northwestern University’s football team voted to unionize claiming they were employees of Northwestern, and thus deserved the right to collectively bargain. In August of 2015, the National Labor Relations Board made the decision that it did not have jurisdiction in the case, effectively blocking the unionization of the athletes. Many saw this as a win for NCAA leaders, who have long argued that paying athletes will result in an unfair marketplace where richer schools are able to scoop up all the best high school athletes by paying a premium.

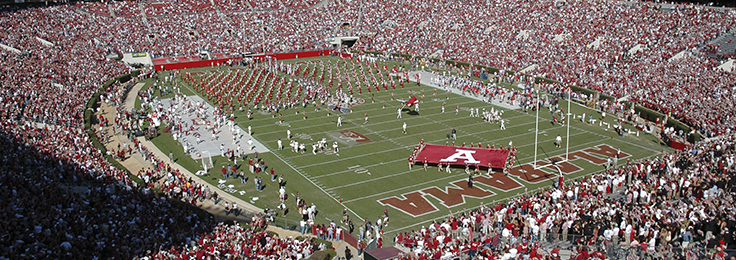

Despite the ongoing debate about whether college athletes should be paid, little research has been done to examine the connection between college athletics programs and the money they make for their academic institutions. Many of these programs bring in millions of dollars annually as highlighted in a December 2015 study in Management Science. “How Much Is a Win Worth? An Application to Intercollegiate Athletics” looks at how each game win during the Division 1 men’s football and basketball seasons translates into dollars for a given sports program. Doug J. Chung, an assistant professor at the Harvard Business School, surveyed data from 117 schools between 2003 and 2013. Chung separated these Division 1 programs into more and less established athletic programs. Power Five Conference teams made up the more established category, while lesser known programs were schools that have a shorter record of athletic success and do not participate in the prestigious conferences, such as the Big 10 and Big 12 conferences.

This study’s findings include:

- Some top schools make up to $200 million from their football and basketball programs annually.

- Wins equal cash for many collegiate football teams. In fact, a single win during the football season could mean as much as a $3 million increase for some top schools. Less established football teams saw a monetary increase as a result of invitations to postseason bowls.

- In general, among the 117 schools surveyed, football programs were far more lucrative than basketball programs. However, basketball programs also brought in significant revenues for schools ranging from $44 million to $123 million annually.

- College sports is a multi-billion dollar industry with several schools reporting revenue around $100 million annually and some top schools bringing in $200 million annually.

Chung mentions in his study that one area for further research is to examine how the revenue for each team and school breaks down in terms of sales categories, such as tickets and team merchandise. Chung, who is an avid college sports fan himself, says he hopes his work will inform the debate on whether and how college athletes are compensated by the schools they represent.

Related Research: A 2015 paper in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, “The Case for Paying College Athletes,” looks at the arguments for and against paying students who play sports for institutions that are NCAA members. A 2016 study published in the Journal of Sport & Social Issues, “The Effects of Revenue Changes on NCAA Athletic Departments’ Expenditures,” finds that “when a school receives additional athletic revenue, expenditures for coaches are 7.5 times more than direct expenditures for athletes (in the form of scholarships) for all NCAA Division I colleges.” A 2016 working paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research, “Academics vs. Athletics: Career Concerns for NCAA Division I Coaches,” examines whether coaches are rewarded for improvements in players’ academic performance. A 2013 report from the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education, “Black Male Student-Athletes and Racial Inequities in NCAA Division I College Sports,” looks at the over-representation of black male student athletes on college football and basketball teams.

Keywords: intercollegiate, education finance, student athletes, athletic stadium,

Expert Commentary