As the 2020 general election quickly approaches, voters across America are poised to cast an unprecedented number of mail ballots to avoid voting in person and risking contracting COVID-19.

In a normal year, most U.S. voters cast their ballots at polling places on Election Day or during early voting. Some vote by mail for various reasons, including being disabled or temporarily located in another state or serving overseas in the military. For the 2018 general election, about one-fourth of voters submitted mail ballots, according to a report the U.S Election Assistance Commission, an independent, bipartisan commission established by the federal Help America Vote Act of 2002, released in 2019.

“By-mail voting (often called absentee voting) allows individuals to receive their ballot in the mail before the election and mark their ballot away from the election office,” the report explains. “The marked ballot can be returned by mail to an election office or, in some states, dropped off at physical polling sites or designated drop-off boxes.”

Some 30.4 million Americans voted by mail for the 2018 general election — not counting citizens living abroad who are allowed to vote absentee under the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act. Election officials rejected 1.4% of these mail ballots for a range of reasons such as arriving late, lacking a required signature and having a signature on the ballot return envelope that does not match the official voter signature on file.

This year, more than 82 million mail ballots have been requested or automatically distributed to eligible voters nationwide, an analysis from the United States Elections Project at the University of Florida shows.

Because mail ballots likely will play a significant role in this year’s presidential election, Journalist’s Resource set out to answer three big questions that many news outlets and their audiences will be pondering. We pored over the academic literature searching for studies that attempt to answer — or at least provide insights on — these three questions:

Does in-person voting raise the risk of COVID-19 infection?

If someone submits a mail ballot, what are the odds it will be rejected?

Do mail-in ballots benefit one political party over another?

Below, check out a sampling of recent journal articles and working papers we think newsrooms will find helpful. Four of them focus on voting in two battleground states — Florida, which allowed election officials to offer early in-person voting as early as Oct. 19, and Wisconsin, where early voting begins today. We provide a summary of each, highlighting key data and findings to help journalists cover these issues on deadline.

———–

Does in-person voting raise the risk of COVID-19 infection?

The following two studies examine voting during the Wisconsin primary election in April. While their findings appear to be contradictory, they are not. The two groups of researchers take different approaches to investigate the issue.

In the first, researchers look at the link between in-person voting and COVID-19 infection statewide, offering a high-level view. In the second study, researchers study in-person voting and positive tests for COVID-19 at the county level, allowing them to spotlight areas where an increase in voters per polling site was associated with a rise in the rate at which people in that state tested positive for the illness.

No Detectable Surge in SARS-CoV-2 Transmission Attributable to the April 7, 2020 Wisconsin Election

Kathy Leung, Joseph T. Wu, Kuang Xu and Lawrence M. Wein. American Journal of Public Health, August 2020.

Voting during the Wisconsin primary in April appears to have been “a low-risk activity,” according to a statewide analysis by researchers from the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Control at the University of Hong Kong and the Stanford University Graduate School of Business.

The April 7 election “produced a large natural experiment to help understand the transmission risks” of COVID-19, the authors write. Of the almost 1.6 million votes cast, about 413,220 were from people who voted in person.

The researchers note that if voters contracted the coronavirus on April 7, infections would have been reported by April 17, on average. Considering the illness’ incubation period, most cases would have been reported between April 11-22.

The researchers learned that the number of COVID-19 tests conducted in the state that month remained stable. Meanwhile, hospitalizations for the illness declined in April.

The Relationship Between In-Person Voting and COVID-19: Evidence From the Wisconsin Primary

Chad D. Cotti, et al. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 27187, October 2020.

This paper provides a more in-depth look at in-person voting and COVID-19 transmission than did the prior analysis, which offers a statewide look at COVID-19 transmission in the wake of Wisconsin’s April primary election. By examining data collected in individual counties rather than across the state, researchers “observed a positive statistical relationship between county level in-person voting per location and COVID-19 spread.”

“Results show that counties which had more in-person voting per voting location (all else equal) had a higher rate of positive COVID-19 tests than counties with relatively fewer in-person voters,” write the authors. “Our results suggest that a 10% increase in voters per polling location leads to about an 18% increase in the test-positive rate.”

The researchers point out that in the weeks leading up to the primary, the Wisconsin Elections Commission allowed election clerks to make changes to the number of voting sites and voting setup. “Among clerks who modified the voting locations available to their registered voters, nearly all sought to consolidate — a decision that almost certainly increased the in-person voter density per voting location,” explain the paper’s authors, from the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh, University of Wisconsin-Madison and Ball State University.

The authors suggest election officials reduce voter density to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

“Although our results are not definitive,” they write, “they do suggest it may be prudent, to the extent possible during the COVID-19 epidemic and weighed against other factors, for policymakers and election clerks to take steps to either expand the number of polling locations, voting times, early voting opportunities, or encourage absentee voting in order to keep the population density of voters as low as possible. The above recommendations could be particularly beneficial to urban voters who face longer weight times and minority voters with substandard voting accessibility.”

If someone uses a mail ballot, what are the odds it will be rejected?

Vote-By-Mail Ballot Rejection and Experience With Mail-In Voting

David Cottrell, Michael C. Herron and Daniel A. Smith. Working paper, October 2020.

This analysis of ballot rejections during three elections in another key battleground state — Florida — finds that election officials were about three times more likely to reject the mail ballots of voters who did not have experience using them, compared with voters who had used mail ballots in prior elections.

In the 2020 primary election, for example, election officials rejected 1.22% of the mail ballots sent by voters who lacked experience using them after those ballots arrived late. They rejected 0.47% of mail ballots submitted by experienced users because of lateness, according to this working paper, from researchers at the University of Georgia, Dartmouth College and the University of Florida.

In this study, researchers deemed voters “experienced” if they submitted mail ballots in the two most recent general elections in Florida and their mail ballots were accepted.

They examined voting records across three elections — the 2016 and 2018 general elections and the 2020 primary election. In Florida, voting records are public, making it possible for researchers to see how many mail ballots were rejected and why. The researchers also were able to disaggregate rejection rates by age, gender and party registration as well as race and ethnicity.

Lack of experience was most harmful to Black and Hispanic voters and voters not affiliated with a major political party. Their mail ballots were most likely to be rejected because they arrived late or lacked a required signature or because of some other voter error — for example, the signature on the ballot return envelopes did not match the official voter signature on file.

“We suspect that one explanation for the latter is that independently minded voters wait longer to vote than do partisans, thus raising the risk of late mail-in ballots,” the authors explain. “This is compounded when independently minded voters are inexperienced with mail-in voting.”

The authors stress that their findings apply specifically to Florida and cannot be generalized to other parts of the country.

“We cannot be sure that our findings on the role of voter experience extend to other states, but the vast majority of states simply cannot be scrutinized in the way that Florida can,” they write.

Voting by Mail and Ballot Rejection: Lessons from Florida for Elections in the Age of the Coronavirus

Anna Baringer, Michael C. Herron and Daniel A. Smith. Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy, September 2020.

In this study of Florida voting records from the 2016 and 2018 general elections, researchers find that younger voters, those needing assistance to vote and those not registered with a major political party were more likely than other voters to have their mail ballots rejected. This paper, however, focuses only on mail ballots that arrived at election offices on time.

“We also find disproportionately high rejection rates of mail ballots cast by Hispanic voters, out-of-state voters, and military dependents in the 2018 general election,” the authors write. “Lastly, we find significant variation in the rejection rates of VBM [vote-by-mail] ballots cast across Florida’s 67 counties in the 2018 election, suggesting a non-uniformity in the way local election officials verify these ballots.”

In November 2016, more than 27,700 mail ballots — about 1% — were rejected despite arriving on time, the analysis reveals. In November 2018, elections officials rejected almost 32,000 mail ballots, or about 1.2%, that made it to election officials on time.

The rejection rate of mail ballots among voters aged 18 to 21 years was 3.9% in 2016 and 5.4% in 2018. The researchers also find that while voters aged 18 to 29 years cast 2.7% of all mail ballots in the 2016 general election, their ballots accounted for more than 11% percent of the mail ballots that arrived by the Election Day deadline but were not counted.

Researchers suggest differences in how election administrators evaluate voter signatures might explain some of the variation in rejection rates.

“Local elections officials have considerable leeway when evaluating the veracity of a signature on a VBM [vote-by-mail] ballot return envelope,” they explain. “Discretion of local election officials or county canvassing boards may result in unequal treatment of VBM ballots due to implicit biases or partisanship, allowing racial or party preferences to be subconsciously present.”

Do mail ballots benefit one political party over another?

Universal Vote-By-Mail Has No Impact on Partisan Turnout or Vote Share

Daniel M. Thompson, Jennifer A. Wu, Jesse Yoder and Andrew B. Hall. PNAS, June 2020.

Does allowing voters to cast their ballots by mail benefit one of the two major political parties more than the other? This study of elections held from 1996 to 2018 in three states finds that universal vote-by-mail — when every voter is mailed a ballot before an election and allowed to mail it back — “does not affect either party’s share of turnout or either party’s vote share.”

It does, however, increase the number of people who vote. An additional 2.1% to 2.2% of the voting age population participates in an election, estimate the researchers, who write that they believe their paper is “the most comprehensive confirmation to date of VBM’s [vote-by-mail’s] neutral partisan effects.”

Daniel M. Thompson, an assistant professor of political science at UCLA, and his colleagues studied elections held from 1996 to 2018 in California, Utah and Washington — three states that rolled out universal vote-by-mail county by county during that period. By comparing counties that had implemented vote-by-mail with counties in the same state that had not yet implemented the policy, researchers were able to study its impact on elections featuring the same set of candidates.

Thompson and his colleagues find that universal vote-by-mail leads to a larger number of people mailing their ballots — an estimated 14% to 19% more.

“As the country debates how to run the 2020 election in the shadow of COVID-19, politicians, journalists, pundits, and citizens will continue to hypothesize about the possible effects of VBM [vote-by-mail] programs on partisan electoral fortunes and participation,” they write. “We hope that our study will provide a useful data point for these conversations.”

America’s Electorate is Increasingly Polarized Along Partisan Lines About Voting by Mail During the COVID-19 Crisis

Mackenzie Lockhart, et al. PNAS, October 2020.

Two national surveys indicate a divide has emerged this year in terms of how voters aligned with the two major political parties want to vote in the 2020 presidential election. In both, Democrats were much more likely than Republicans to say they preferred to cast their ballots by mail.

Researchers used online surveys to ask two groups of eligible voters — 5,612 people in April and then 5,818 in June — how they wanted to vote and whether they support national legislation requiring states to provide absentee ballots for all voters requesting them.

“In April, 40.1% of Democrats indicated that they would like to vote by mail in November while 30.5% of Republicans wanted to vote by mail,” the authors write. “In June, this gap doubled as 44.8% of Democrats and only 25.5% of Republicans indicated they would like to vote by mail at this point.”

The surveys show high levels of support for national legislation requiring states to provide absentee ballots to voters who want to use them. In April, 87.3% of Democrats supported the proposal as did 64.1% of Republicans. In June, though, support was 2.3% lower for Democrats and 12.6% lower for Republicans, “suggesting an increasing partisan divide on the issue,” the authors write.

The researchers write that news outlets could be partly to blame for the change.

“One potential explanation for this is increasing media coverage that frames voting by mail as a partisan issue,” they write.

For more information to help you cover the 2020 election, see these 10 tips from the experts and our research roundup on voter intimidation.

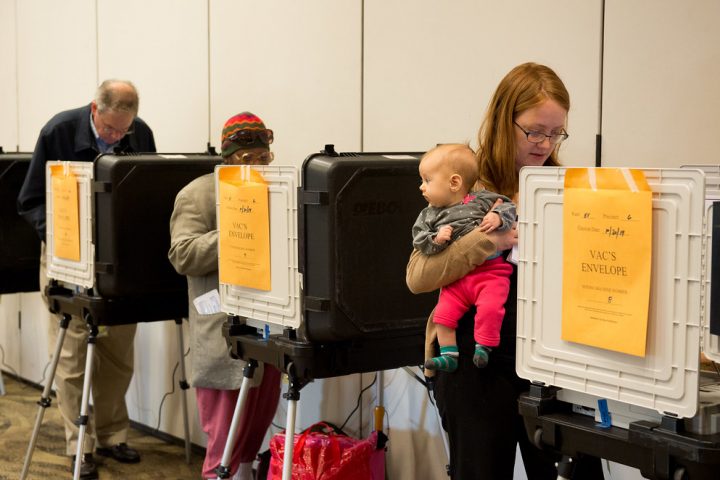

This image was obtained from the Flickr account of Maryland GovPics and is being used under a Creative Commons license. No changes were made.

Expert Commentary