In recent decades, low- and middle-income countries such as Chile, Costa Rica, Cuba and China have succeeded in dramatically improving their citizens’ health. The number of people living below the poverty line has also fallen significantly in many large countries: Between 1981 and 2005, China’s poverty rate dropped from 84% to 16%, India’s from 60% to 42% and Brazil’s from 17% to 8%. Within Africa, Ghana and Senegal halved their incidence of poverty between the mid-1990s and 2010. Furthermore, the highest rates of GDP growth over the past decade have been in East Asia (8%), South Asia (7%) and Sub-Saharan Africa (5%) — “the three regions which account for the bulk of absolute poverty” globally, according to a 2013 World Bank study.

Despite these positive trends, there continue to be massive gaps in the degree of human development among countries. Comparing the lives of people in Norway, Australia and Switzerland — the three most developed countries, according to the United Nations — to those in Congo, Niger and the Central African Republic — the least developed — astonishing disparities emerge across all measures of health, wealth, security and well-being. And the World Bank’s most recent data show that 48.5% of the population in Sub-Saharan Africa still lives on $1.25 or less a day.

For more than two decades, the United Nations Development Programme has issued an annual review that details the quality of life for people around the world. The “Human Development Report 2014: Sustaining Progress: Reducing Vulnerabilities and Building Resilience,” by lead author Khalid Malik and a team of researchers, focuses on “structurally vulnerable” groups of people. While the report acknowledges that “overall global trends are positive and … progress is continuing” and that “globalization has brought benefits to many,” it focuses on the precariousness of life for billions around the world. The authors state that the “sustained enhancement of individuals’ and societies’ capabilities is necessary to reduce these persistent vulnerabilities — many of them structural and many of them tied to the life cycle.” The report also includes a ranking of all countries, 1 to 187, in its Human Development Indices table.

Key descriptive data from the report includes:

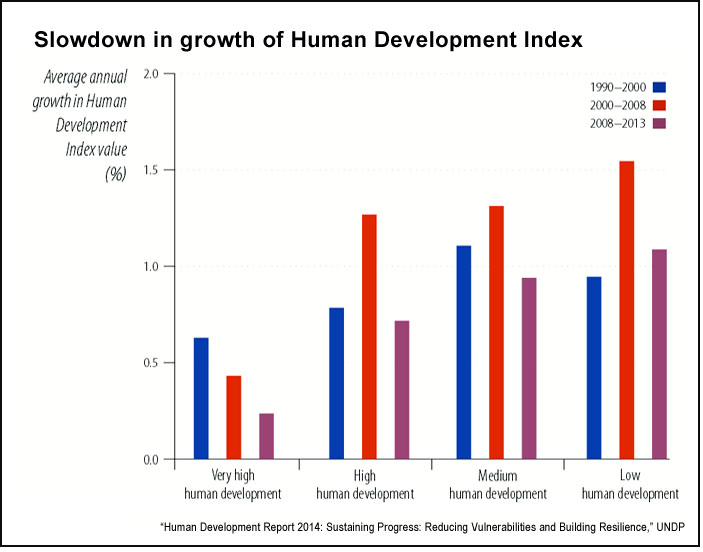

- Over the past two decades, development rates accelerated in many poorer nations: “More than 40 developing countries — with the majority of the world’s population — had greater gains on the Human Development Index than would have been predicted given their situation in 1990,” when the first Human Development report was issued. But this progress has slowed over the period 2008-2013.

- “Despite recent progress in poverty reduction, more than 2.2 billion people are either near or living in multi-dimensional poverty…. That means more than 15% of the world’s people remain vulnerable to multi-dimensional poverty. At the same time, nearly 80% of the global population lack comprehensive social protection. About 12% (842 million) suffer from chronic hunger, and nearly half of all workers — more than 1.5 billion — are in informal or precarious employment.”

- There is mixed news in terms of distribution of money and resources: “Average loss of human development due to inequality has declined in most regions in recent years, driven mainly by widespread gains in health. But disparities in income have risen in several regions, and inequality in education has remained broadly constant.”

- “In developing countries (where 92% of children live) 7 in 100 will not survive beyond age 5, 50 will not have their birth registered, 68 will not receive early childhood education, 17 will never enroll in primary school, 30 will be stunted and 25 will live in poverty. Inadequate food, sanitation facilities and hygiene increase the risk of infections and stunting: Close to 156 million children are stunted, a result of undernutrition and infection.”

- For the elderly, there continues to be little safety net, as “roughly 80% of the world’s older population does not have a pension and relies on labor and family for income.”

- Young people around the world continue to have difficulty finding work, hurting their life chances over the long run. The period during ages 15 to 24 is the “transition when children learn to engage with society and the world of work” and a time when young persons are especially “vulnerable to marginalization in the labor market.” Indeed, “in 2012 the global youth unemployment rate was an estimated 12.7%, almost three times the adult rate.”

- Rising levels of violence are significantly impeding development globally: “More than 1.5 billion people live in countries affected by conflict — about a fifth of the world’s population. And recent political instability has had an enormous human cost — about 45 million people were forcibly displaced due to conflict or persecution by the end of 2012 — the highest [number] in 18 years — more than 15 million of them refugees.”

Beyond the analytical data, the report also spells out how policymakers can work to make societies more resilient: The authors call for “universal access to basic social services, especially health and education; stronger social protection, including unemployment insurance and pensions; and a commitment to full employment, recognizing that the value of employment extends far beyond the income it generates.”

Keywords: poverty, Asia

Expert Commentary