Since the beginning of the Syrian conflict in 2011, more than 2 million refugees have been displaced from their homes. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), as a result of the conflict more than 6.5 million people within Syria require immediate humanitarian assistance, and an estimated 9.3 million are in need of aid. The sheer scope of this complex situation makes it among the largest humanitarian crises in recent history.

With limited access into the country for humanitarian groups, the number of refugees arising from the Syrian conflict may climb up to 4 million people in 2014, according to UNHCR. As international donors gather for the Kuwait II Donors Conference to discuss the crisis, there are growing concerns around the wellbeing of Syrian refugees and their access to humanitarian aid. NGO reports of border restrictions, child labor, forced marriage and human smuggling have surfaced. Groups such as Doctors Without Borders and Amnesty International have recently highlighted particularly urgent aspects of the crisis.

Two January 2014 reports from Harvard University provide on-the-ground insights into these growing problems. A new report drawn from field work in Lebanon, where more than 500,000 refugee children now live, documents patterns over 10 days in November 2013. The lead authors are Susan Bartels and Kathleen Hamil. The onset of winter has heightened dangers and uncertainty for this vulnerable population, the researchers note. The report concludes:

Compelled to choose between sending their children to work in potentially dangerous environments or foregoing basic needs, many families rely on child labor. Even when families can afford for their children to spend precious working hours in school, refugee children have limited, if any, access to education. These constraints deprive children of sufficient food, education, health care, and play, and in doing so they hamper children’s short- and long-term physical and psychosocial development. From both a humanitarian and a human rights perspective, the Syrian refugee crisis in Lebanon is intolerable. From the public health standpoint, the survival needs of the population are approaching catastrophe.

Another new field study based in Jordan looks at wider refugee problems being generated by the conflict. That Harvard report — written by a team led by Claude Bruderlein — assesses the refugee crisis and the international responses, issues around refugee status and rights, refugee living conditions and the distribution of international responsibilities. In January 2014, the researchers conducted interviews with government representatives, NGOs and refugees as well as reviewed a variety of secondary sources to arrive at preliminary findings on issues surrounding the Syrian refugee debate.

The report’s findings include:

- Contrary to popular belief, most of the Syrians who have fled to neighboring countries live in urban settings, not camps. In the five key host countries (Turkey, Lebanon, Iraq, Egypt and Jordan), the number of refugees living in non-camp settings is expected to rise from 81% in 2013 to 84% in 2014.

- Even where camps are available, refugees prefer to live in urban settings. The registered refugee population of Jordan’s Za’atari camp declined by almost 40% between April and December 2013, at the same time that Jordan received an additional 100,000 refugees.

- Refugees appear willing to make significant sacrifices to leave camps. According to a survey by CARE International, more than 50% of participating refugee households living outside Jordanian camps reported incurring debts to smugglers of between 75 and 1,500 Jordanian dinars (roughly $105 to $2,115 U.S.)

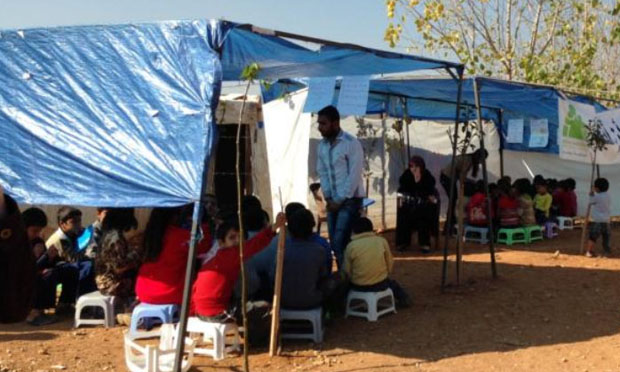

- The limited supply of housing and economic opportunities have resulted in an average Syrian household size of 6.2, forcing large numbers of people into unsuitable settlements such as tents, chicken coops, and garages. These overcrowded informal settlements lack basic amenities, such as electricity, heating, and access to water.

- While the 1951 Refugee Convention and the corresponding 1967 Protocol were meant to protect the rights of all refugees, many displaced Syrians are in nations such as Lebanon, Iraq and Jordan that are not signatories to the 1951 and 1967 protocol, or have signed them with geographical limitations (Turkey).

- Host communities have been dramatically affected by the influx of Syrian refugees. For example, affordable housing is not available in many northern regions of Jordan, where monthly rents have increased from JOD 40-50 ($56 to $70 U.S.) before the crisis to an average of JOD 300 (about $420 U.S.). Strains on public education, health services and water and energy resources have heightened social tensions in some instances due to the limitations of municipal capacity to cope with the increased demand.

While humanitarian intervention in Syria has been discussed at length, there is also a clear need for solutions to deal with the largest refugee crisis in the history of the Middle East, the researchers note. Innovative programs and policies to address the short- and medium-term needs of refugees and host communities will be essential to the long-term stability of the Middle East.

Keywords: Syria, refugee, refugee rights, communities, protection

Expert Commentary