Recent events around the globe have amply demonstrated that one person’s revolution is another’s coup.

The ongoing crisis in Ukraine began with rallies denouncing then-President Viktor Yanukovych’s broken promise to sign political and free-trade agreements with the European Union. Depending on whom you ask, Yanukovych’s subsequent departure from Kiev was the result of either a people’s revolution or a coup that violates Ukraine’s constitution. Similarly, only a year after Egypt’s Mohamed Morsi was sworn in as president, he was ousted after a series of public protests even larger than the ones that removed his predecessor, Hosni Mubarak. Once again, Egyptians gathered in Tahrir Square to protest their current regime, this time supported by the same army they criticized in 2011. Unsurprisingly, Egyptian officials who opposed the Muslim Brotherhood championed Morsi’s removal as the result of a popular uprising, while Morsi supporters accuse the military of mounting a coup.

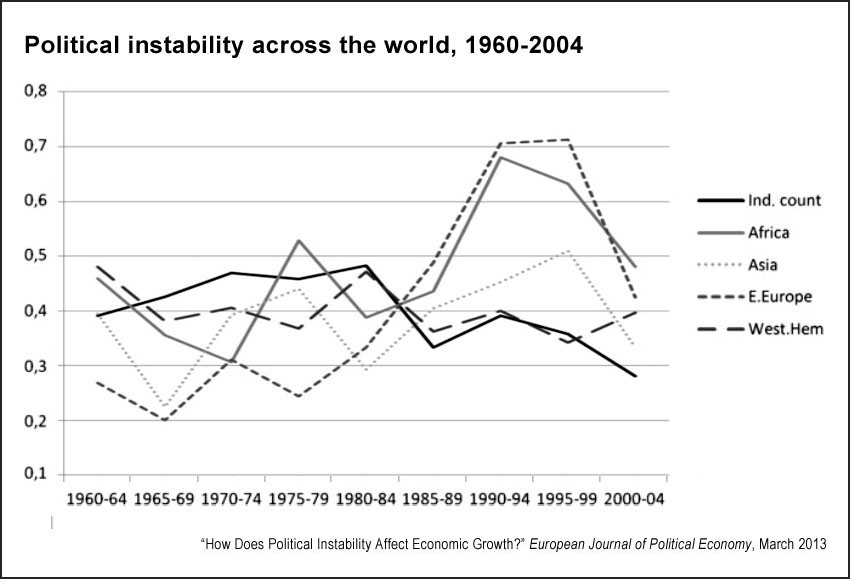

A 2013 study in the European Journal of Political Economy examined political instability in more than 200 countries from 1960 to 2004. Instability was gauged by the number of times in a year in which a country had a new premier and/or when half or more of the cabinet ministers changed.

The above chart shows that rates of instability vary significantly from region to region over the period studied. For example, the 1991 fall of the Soviet Union unleashed a wave of political change in Eastern Europe: By 1994 more than 70% of the countries in that region had had a regime change of some sort. Some transformations were peaceful, others extremely violent, and in some cases — as with Ukraine — the process continues.

Beyond the implications for the affected countries, the distinction between “protest” and “coup” can hold significant consequences when it comes to foreign aid. The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2012 requires the United States to withdraw nonhumanitarian aid from “the government of any country whose duly elected head of government is deposed by military coup d’état or decree or, after the date of enactment of this Act, a coup d’état or decree in which the military plays a decisive role.” A 2012 study in the Harvard International Law Journal argues that changes of power should be assessed in a more balanced way, however: “The conventional view, which views all coups as a menace to democracy and stability, should be replaced with a more nuanced approach to evaluating their desirability that takes into account coups that produce democratic regimes.”

A 2014 paper in the Journal of Politics, “Popular Protest and Elite Coordination in a Coup d’État,” looks at the relationship between popular protests and coups. The researchers — Brett Allen Casper and Scott A. Tyson of New York University — focus on how popular uprisings can affect the coordination of coups among elites (leaders in the political class), emphasizing that both acts test the ability of governments to withstand pressure. Casper and Tyson develop a model using data from the Cross-National Time-Series Archive and the Center for Systemic Peace coups database. The scholars also examined how variations in media freedom affected the relationship between large-scale protest movements and coups.

Findings from the NYU study include:

- Mass protests increase the probability of a coup attempt, but the degree depends on a country’s level of media freedom: “The change in the effect of protests on coups is almost four times bigger when one moves from a partially free press to a fully free press.”

- Popular discontent affects the behavior of elites in two ways: “First, protests provide elites with information which helps them better ascertain the ability of the leadership to withstand a coup. Second, the publicity of the protest causes elites to sharpen their beliefs about what other elites will do, thus reducing the strategic uncertainty associated with participating in a coup.”

- Increased media freedom reduces elites’ “strategic uncertainty,” allowing them to better know whether a coup attempt is likely to be successful: “Media freedom, through its influence on the dispersion of citizen beliefs, affects the precision of elite expectations regarding the actions of other elites. When media is free, citizens are more likely to correctly align their own actions. When citizens correctly align their actions, the aggregate signal the protest provides to elites is more sensitive to leadership characteristics.”

- In a brief case study of Libya, the researchers note: “Since Libya in 2011 was an extremely restricted regime with virtually no social media nor an independent press, the recent protests in Libya were unhelpful for ambitious elites, which insulated Gaddafi from a coup (but not NATO-assisted rebels).”

The findings lead the authors to hypothesize that there have not been more coups in the post-Arab Spring Middle East due to restrictions on media freedom throughout the region. Elites haven’t had sufficient information on citizen beliefs to mount coups, and as a consequence, governments instead fall due to popular pressure.

Related research: For additional information on the uprisings of the Arab Spring, see studies on the political protest model and the role of social media in the upheaval. Also of interest is “People Power or a One-Shot Deal? A Dynamic Model of Protest,” which examines the probability of new mass, revolutionary protests if new regimes turn out to be just as unsatisfying to citizens as old ones. The scholars — Adam Meirowitz of Princeton and Joshua A. Tucker of NYU — note that there is a fundamental difference between a regime change and a change of government without a new regime. “The conditions that can lead to ‘one-shot-deals’ seem especially plausible in countries without much of a prior history of democracy, such as Egypt and the Ukraine,” because citizens of new democracies “are not just learning about the quality of their new leaders following a successful protest, but rather may be learning (or think they are learning) something fundamental about the universe of potential leaders in their country.”

Keywords: armed conflict, Russia, Vladimir Putin, Egypt, Syria, Libya, Arab Spring

Expert Commentary