The traditional borders and spheres of influence of the nation of Iraq appear to be deteriorating and shifting, perhaps giving way to a new, unknown order in that vast region in the Middle East.

One of the primary forces driving these violent and chaotic changes is the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, or al-Sham (also referred to as ISIS, or ISIL), a jihadist Sunni group that has poured out of Syria and has advanced rapidly toward Baghdad and other cities. That group is led by Abu Bakr Al Baghdadi, who has drawn together fighters from around the region — and Sunni sympathizers within Iraq — and organized a fighting force estimated at perhaps 7,000. While this figure is impressive, according to a 2013 report from the Center for Strategic & International Studies, Iraq’s Ministry of Defense has 279,103 personnel (primarily the army, air force and navy), while the Ministry of the Interior has 649,800 (local and federal police, as well as other units ) — a total of 933,103. Yet the insurgent fighters have succeeded in driving many Iraqi soldiers to desert posts and leave their command structures.

Both Sunni Kurds in Iraq’s north, with their Peshmerga fighting force, and the Shiia majority that rules the country, led by Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki, are resisting this insurgent advance. Meanwhile, both Turkey and Iran have interests that they perceive are being threatened. And there are of course calls for the United States to renew its involvement in Iraqi governance and politics, as well as to help with military strikes or tactical assistance.

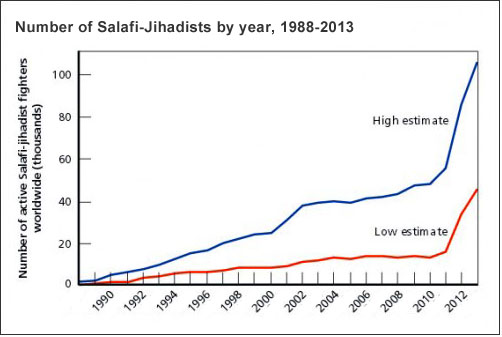

The names, affiliations and relative capacities of terrorist and jihadist groups continue to morph; for a detailed analysis of the latest trends, see the RAND Corporation’s 2014 report, “A Persistent Threat: The Evolution of al Qa’ida and Other Salafi Jihadists,” by Seth G. Jones. He notes:

In Iraq, the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham has significantly increased its attack tempo since 2011, focusing on Shi’a and Iraqi government targets. In fact, the group has likely targeted more Shi’a than every other al Qa’ida affiliate combined. By 2013, attacks by the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham had surpassed levels in 2011, the last year that U.S. military forces were in Iraq, and controlled small amounts of territory in areas like Fallujah in Al-Anbar Province. Most were vehicle-bomb attacks, with smaller numbers of suicide attacks. In neighboring Syria, the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham’s seizure of weapons and money from Syrian rebel groups, execution of some rebel leaders, and refusal to participate in peace talks triggered a backlash. Several groups, including the Islamic Front, Syrian Revolutionary Front, and even Jabhat al-Nusrah engaged in heavy fighting with the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham.

The RAND report also includes this useful data on the global rise of jihadist movements and fighters over time:

For in-depth perspective on Syria’s civil war and its relationship to Iraq, see the May 2014 Congressional Research Service report “Armed Conflict in Syria.”

The following are additional reports from think tanks and research institutions that can help put events in Iraq and Syria into wider context:

_______

“Iraq: Politics, Governance, and Human Rights”

Katzman, Kenneth. Congressional Research Service report, March 2013.

Excerpt: “Ten years after the March 19, 2003, U.S. military intervention to oust Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq, accelerating violence and growing political schisms call into question whether the fragile stability left in place after the U.S. withdrawal from Iraq will collapse. Iraq’s stability is increasingly threatened by a revolt — with both peaceful and violent components — by Sunni Arab Muslims who resent Shiite political domination. Sunni Arabs, always fearful that Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki would seek unchallenged power, accuse him of attempting to marginalize them politically in part by arresting or attempting to remove key Sunni leaders. Sunni demonstrations have grown since late December 2012 and some have led to protester deaths. Iraq’s Kurds are increasingly aligned with the Sunnis, based on their own disputes with Maliki over territorial, political and economic issues. The Shiite faction of Moqtada Al Sadr has been leaning to the Sunnis and Kurds, and could hold the key to Maliki’s political survival. Adding to the schisms is the physical incapacity of President Jalal Talabani, a Kurd who has served as a key mediator, who suffered a stroke in mid-December 2012 and remains outside Iraq. The rifts have impinged on provincial elections on April 20, 2013, and will likely affect national elections for a new parliament and government in 2014. Maliki is expected to seek to retain his post in that vote.

The violent component of Sunni unrest is spearheaded by the Sunni insurgent group Al Qaeda in Iraq (AQ-I). The group, apparently emboldened by the Sunni-led uprising in Syria, is conducting attacks against Shiite neighborhoods and Iraqi Security Force (ISF) members with increasing frequency and lethality. The attacks are intended to reignite all-out sectarian conflict, and some fear that goal might be realized. Should the violence escalate further, there are concerns whether the ISF — which numbers nearly 700,000 members — can counter it now that U.S. troops are no longer in Iraq.”

“Shaping Iraq’s Security Forces”

Cordesman, Anthony H.; Khazai, Sam; Dewit, Daniel. Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), December 2013.

Excerpt: “In fairness, part of the problem was that the U.S. had tried to impose too many of its own approaches to military development on an Iraqi structure that had no internal checks and balances to make them function once U.S. advisors were gone. As in Vietnam and Afghanistan, the U.S. accomplished a great deal, but it tried to do far too much too quickly with more emphasis on numbers than quality, and grossly exaggerated unit quality in many cases…. Many elements of Iraqi forces did become effective while U.S. forces were present and stayed effective after they left, but successful force building takes far longer than the U.S. military was generally willing to admit and U.S. efforts to transform — rather than improve — existing military cultures and systems have often proved to be counterproductive and a waste of effort.

The U.S. learned, even before Iraq failed to grant U.S. advisors immunity, that tactical-level proficiency, while a critical core competency for any military unit, is often also the easiest to instill…. Creating a U.S.-shaped process of logistics and upper-echelon planning capabilities, and a command culture that supported initiative and decision-making at junior levels proved far more difficult and many aspects could not survive the departure of U.S. advisors and the loss of U.S. influence.”

“The Fall and Rise and Fall of Iraq”

Pollack, Kenneth. Saban Center, Brookings Institution, Middle East Memo No. 29, July 2013.

Excerpt: “[I]t may still be possible for the United States to begin to rebuild its influence in Iraq. It will be a slow and arduous process, and it will require the Obama Administration to do the one thing it has absolutely refused to do all along: treat Iraq as an important element of American vital interests, one deserving of time, energy and even resources (albeit far, far less than had been the case at the height of the U.S. occupation). If Washington is willing to do that, we might find an Iraqi government still desirous of working together to turn the SFA [U.S.-Iraqi Strategic Framework Agreement] from an idea to a program. Indeed, on its own, the Iraqi government has again begun to signal that it wants to rebuild ties to Washington, including by resuscitating the SFA. It is exactly the opening we need. There are, moreover, any number of ways in which the United States could deliver tangible assistance to Iraq at a relatively low financial cost. For instance, under the rubric of the SFA, we might establish a joint economic commission to serve as a central oversight body to coordinate, monitor, and provide technical expertise for reconstruction and capital investment projects initiated with Iraqi funds….

Second, Washington could shift from a devotion to quiet diplomacy favoring the Maliki government to the occasional embrace of public diplomacy that chastised it for its misbehavior along with that of its rivals. The Administration is right that Maliki’s opposition has not covered itself in glory, but they are wrong to claim that Maliki’s actions have not been harmful too — or have been less harmful. Simply as the government, their actions are inevitably much more damaging than anything the opposition might do because of the precedent they set and the fear they sow….

Third, although taking the steps necessary to end the Syrian civil war seem far beyond what this Administration is willing even to imagine, lesser steps there might have benefit for Iraq. In particular, providing greater aid to the Syrian opposition might give Washington more cards to play with both Turkey and the Sunni Arab states — all of whom want to see a greater American role in Syria. The United States might then trade its moves in Syria for help in Iraq.”

“Islamic State in Iraq and Greater Syria”

Laub, Zachary; Masters, Jonathan. Council on Foreign Relations backgrounder, June 12, 2014.

Excerpt: “Insurgents’ consolidation of territorial control is a concern for the United States, which believes such areas outside of state authority may become safe havens for those jihadis with ambitions oriented toward the “far enemy” — the West. The Obama administration has responded to the regional resurgence by increasing the CIA’s support for the Maliki government, including assistance to elite counterterrorism units that report directly to the prime minister, and providing Hellfire missiles and surveillance drones. After Iraqi forces retreated from Mosul, the insurgents who routed them released more than one thousand prisoners and picked up troves of U.S.-supplied matériel.”

“Iraq: Falluja’s Faustian Bargain”

International Crisis Group, Middle East Report No. 150, 28 April 2014.

Excerpt: “Sunni groups have been all too willing to play along with the government’s divide- and-rule strategy. Should this communal competition continue, the election gambit risks becoming an open-ended intra-Sunni struggle. The military council and Muttahidun, rather than vilifying each other, should work together on crucial tasks, such as securing public order; selecting a new mayor and police chief; and demanding that the government boost police and tribal sahwat forces that, if they cooperated, likely could evict al-Qaeda. Chief responsibility for unifying Sunni ranks, however, lies with the community itself. This is essential for crafting a strategy of positive engagement with the national political process that might enable Sunnis to negotiate, at the central government level, greater authority for their provincial bodies and authorities (e.g., provincial council, governor) to manage their own political and security affairs.

Iraq needs genuine reconciliation and integration, but the election campaign has pushed it in precisely the other direction. It has not been an exercise in national unity, but rather an occasion for the government to seek its mandate by opposite means. Baghdad has used the polls to set Sunnis against Shiites, and Sunnis against Sunnis, in the name of battling terror and al-Qaeda. The irony is that these goals are not mutually exclusive: Iraq could yet have far more success in fighting extremism were it to do so as a unified polity.”

“The End of Sykes-Picot? Reflections on the Prospects of the Arab State System”

Rabinovich, Itamar. Saban Center, Brookings Institution, Middle East Memo No. 32, February 2014.

Excerpt: “In January 2014, the most radical jihadi group operating in Syria, ISIS (Islamic State in Iraq and Syria), consisting mostly of radical Sunni jihadis from Iraq, transferred the edge of its activities to Iraq itself and captured parts of cities of Falluja and Ramadi, thus posing a severe challenge to the al-Maliki government and underscoring the interplay between the Syrian and Iraqi crises. The very name, ISIS, implies the notion that a Sunni victory in Syria would lead to the creation of an entity friendly to Iraq’s Sunnis across the border. This is not a sentiment shared so far by the majority of Iraq’s Sunnis who are not quite ready to secede from Iraq and is limited to the radical jihadis.

Iraq’s civil war burned hottest in the middle of the last decade, and the fire is not out. Indeed, the Syrian war has added fuel, with thousands dying in 2013 in sectarian violence. Partition there remains a possibility. Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki has built an authoritarian system that rests mostly on the Shiite-Arab majority and has sharply antagonized the Sunni-Arab population that feels disenfranchised after centuries of hegemony. The Sunni minority concentrated in the north-western part of the country is estranged from the current Iraqi state and the government in Baghdad has a limited sway over this part of the country. This area serves as the territorial link between the Syrian civil war and the ongoing conflict in Iraq, and has been described above, serves in turn to inflame one party or the other. The Kurdish region in the north enjoys full autonomy and is economically flourishing.

The gloomy status quo in Iraq could persist in the coming years unless a radical domestic or external development serves to convert the potential for radical change into an actual one. For now, neither the Kurds nor the Sunnis are ready to separate — Iraqi national identity remains real. Saddam Hussein invested a massive effort in trying a legacy and a distinct identity for Iraq that would integrate the three major communities into one polity. His success was not full, but the notion of a distinct Iraqi entity is there. Nor should the significance of oil revenue be taken lightly. For Iraq’s Sunnis to secede from Iraq would be to abandon their claim for their share in its oil income. At this point they would rather fight for their position inside Iraq than secede from it. The gloomy status quo in Iraq could persist in the coming years unless a radical domestic or external development serves to convert the potential for radical change into an actual one. In this context, the future course of the Syrian crisis and its interplay with Iraq’s domestic conflict seems to be the most likely source for such a change.”

“Iraq Ten Years On”

Spencer, Claire; Kinninmont, Jane; Sirri, Omar, editors. Chatham House, May 2013.

Excerpt from Chapter 5: “The greatest political challenge facing Iraq today is its transition from a power-sharing to a majoritarian form of government without a concomitant depoliticization of ethno-sectarian identities. Power-sharing is an ineffective system of government. It is often introduced into ‘deeply divided societies’ on the basis that countries made up of numerous religious or ethnic groups must ensure that these are properly represented in government in order to prevent civil conflict. There are two key flaws in this model. The first is the assumption that communal groups must be represented by their own kind in government, and the second is the notion that ethno-sectarian identities will remain the most important political cleavages in a given society.”

Keywords: Middle East, terrorism

Expert Commentary