Young voters have been a major voting bloc since 1971, when the U.S. lowered the federal voting age from 21 to 18. Today, they are one of America’s largest voting blocs — about 50 million people aged 18 to 29 with the potential to sway elections nationwide.

This year, young voters are most likely to shape the 2024 presidential election in 10 states: the seven battleground states of Georgia, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, Nevada and Arizona as well as Virginia, New Hampshire and Minnesota, according to an analysis from Tufts University’s Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement. The center, commonly known as CIRCLE, ranks the states where young adults are most likely to influence races for president and the U.S. House and Senate using its Youth Electoral Significance Index.

It’s tough to predict how many young adults will vote in any given election, however, partly because their turnout rates vary considerably by state and year. Also, many college students get to pick the state they will vote in. Those who leave their home state to study in another state can usually vote in either state — although some states, since the 2020 election, have made it harder for out-of-state students to vote where they go to school.

Historically, young voters have had the lowest turnout of any age group. But their voting rates spiked in recent years. Half of young voters participated in the 2020 presidential election, up from 39% in 2016, CIRCLE researchers estimate, adding that it was likely one of the highest turnout rates for young voters since the voting age dropped to 18.

Even the youngest voters showed up in higher numbers for that election: 51% of U.S. citizens aged 18 to 24 voted in 2020, compared to 46% four years earlier, data from the U.S. Census Bureau show.

Who are young voters?

Most young voters are members of Generation Z, the most racially and ethnically diverse generation of Americans who also have never known a world without the internet. Roberta Katz, a senior research scholar at Stanford University who studies Gen Zers, describes them as highly collaborative and self-driving.

In the workplace, they value direct communication, authenticity and relevance, according to Katz, coauthor of the 2021 book “Gen Z, Explained: The Art of Living in a Digital Age.”

“They also value self-care,” she told the Stanford Report in 2022. “They may be more likely than older people were when they were the age of the Gen Zers to question rules and authority because they are so used to finding what they need on their own.”

As a whole, young voters tend to be politically progressive, finds an April 2024 analysis from the Pew Research Center. But many do not identify directly as Democrats or Republicans. About half of voters under age 25 identify as independent or something else. The other half are partisan “leaners” — 28% say they lean Democratic and 20% say they lean Republican, Pew Research Center data show.

A new survey, conducted with a nationally representative sample of young voters, finds they favor Vice President Kamala Harris over former President Donald Trump in the 2024 presidential race. Harris leads Trump by 20 percentage points among registered voters under 30 and by 28 points among those who say they will likely vote, according to the Harvard Youth Poll, released Sept. 24 by the Harvard Kennedy School’s Institute of Politics. The Journalist’s Resource also is located at Harvard Kennedy School.

The results of that survey also suggest young voters will be more likely to vote if their friends vote — 79% of those who believe their friends will vote said they also plan to vote. Meanwhile, 35% of those who do not think their friends will vote plan to vote themselves. The voting behavior of family and friends tends to influence the voting habits of people across age groups, research suggests.

CIRCLE estimates that 40.8 million Gen Zers will be eligible to vote on Nov. 5. The Census Bureau estimates there were 53.1 million adults under 30 living in the U.S. in April 2023, some of whom would not be eligible to vote in federal elections because they are not U.S. citizens or registered to vote or because they do not meet their state’s residency requirements. In most states, adults with a felony conviction also cannot vote while they are incarcerated.

Factors that affect young voter turnout

Journalists who cover young voters need to understand the various factors that can influence their voting habits, says John Holbein, an associate professor of public policy, politics and education at the University of Virginia.

He warns journalists not to assume lower turnout means young voters are generally lazy, apathetic or uninterested in politics. Many young adults face significant barriers throughout the voting process — from figuring out how to register to vote to getting to polling places or submitting a mail-in ballot correctly, says Holbein, coauthor of the 2020 book “Making Young Voters: Converting Civic Attitudes into Civic Action.”

“Young people told us again and again in my research for my book that they want to vote but they have difficulty following through on those good intentions,” he says.

Transportation is one of the larger hurdles. Traveling to election offices and polling places can be tough without a reliable vehicle, public transportation or money to take a cab or use a ridesharing service. In many parts of the U.S., especially in more rural areas, young people have limited or no access to ridesharing services such as Uber and Lyft.

Voter identification requirements can be another barrier. Many young adults do not have driver’s licenses, the most common form of voter ID. Since the most recent general election, several states stopped allowing students to use their student ID for voting. In August, the U.S. Supreme Court reinstated a provision of a state law in Arizona that requires residents to provide documentation of their U.S. citizenship to register to vote.

When CIRCLE researchers surveyed young adults who did not participate in the 2022 midterm elections, they found that 1 in 5 young voters had difficulty registering to vote. CIRCLE researchers also learned that young adults who had been contacted by any organization about the 2022 election prior to the election were much more likely to vote than young adults who had not been contacted about the election.

“One reason young people may be unsure about the importance of their vote or have insufficient information about the election is a lack of outreach from campaigns and organizations,” CIRCLE researchers write in a December 2022 report. “There was a 29-point gap in self-reported voter turnout between young people who were contacted at least once and those who were not contacted at all.”

For young adults who leave home to go to college in another state, deciding where to vote can be difficult, adds Menlo College Dean of Arts & Sciences Melissa Michelson. These students must weigh the pros and cons of voting in their home state against voting in the state where they go to school.

“That’s like a complicated math equation in a way,” says Michelson, a political scientist who has coauthored multiple books and research articles on voter mobilization.

“[Out-of-state students] have to keep in mind: Where will my vote matter more? What are the different rules?” she adds. “Maybe they’re going to school in state that maybe makes it really easy or makes it quite difficult to vote. They have to think: If I vote at home, can I access my ballot in time? They have to decide: Should I vote at my school address so I can stand in line and vote, versus the stress of getting and filling out a mail ballot in time? I just think that’s a lot to ask an 18-year-old.”

Voting and the Higher Education Act

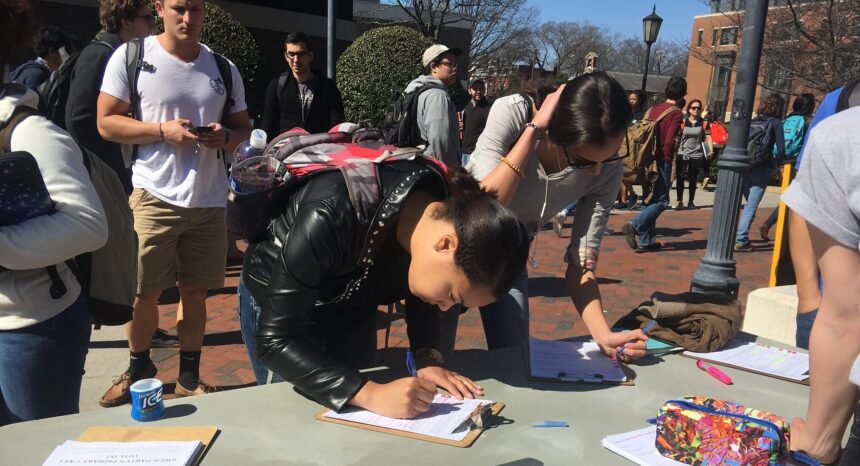

The vast majority of colleges and universities are required by law to give students voter registration information, if their state requires voter registration and does not allow it at the time of voting. The federal government mandates higher education institutions do this during years when there are elections for federal offices and when their state holds elections for governor or other state-level offices.

The Higher Education Act of 1965 was amended in 1998 to require schools to “make a good faith effort to distribute a mail voter registration form, requested and received from the State, to each student enrolled in a degree or certificate program and physically in attendance at the institution, and to make such forms widely available to students at the institution.”

Since then, institutions have rolled out a variety of programs and initiatives to educate students about elections and encourage them to vote. For example, 1,078 colleges and universities have joined the ALL IN Campus Democracy Challenge, a national, nonpartisan program launched in 2016 to improve college student turnout and civic engagement.

Participating schools submit data on their student voting rates in national elections and are recognized for their work. In September, St. Olaf College, a small, private college in Minnesota, received a Champion Campus Award for having the highest student voting rate in the 2022 midterm election. Ninety percent of its students were registered to vote for that election and 67% voted, St. Olaf notes on its website.

Academic research to help journalists report on young voters

To help journalists better understand and report on young voters, we gathered academic articles on the topic and summarized them. Below, we highlight the key takeaways of five papers that examine young voters from three angles: factors that influence their picks for president, how out-of-state college students decide where to vote, and the role colleges and universities play in boosting student voting rates.

Some of the main findings of those papers:

- The most selective higher education institutions in the U.S. generally have the highest student voting rates. Community colleges have the lowest. However, the voting rate of community college students was higher than the voting rate of young adults who did not go to college.

- Among U.S. colleges and universities, having a larger number of students, a larger number of Black students and fewer Pell grant recipients was associated with higher student voting rates.

- In 2020, young adults in Arizona who considered their neighbors trustworthy were more likely to say they planned to vote for President Donald Trump in that year’s election.

- When researchers surveyed students at several colleges and universities prior to the 2020 presidential election, they found that Black, Hispanic and white students who agreed more strongly with the statement “I feel safe with Donald Trump as president” were more likely to say they had voted for Trump or planned to vote for him.

- In the same survey, Black and Hispanic students who said they believe the Bible to be “the actual word of God” and that it is “to be taken literally” were more likely to say they voted for Trump or planned to vote for him, compared with students who said they believe the Bible is the “inspired word of God” or “a book of fables written by men.”

- College students who have the option of voting for president in their home state or the state where they go to school tend to choose the state where they think the race will be more competitive.

Mandi Bates Bailey, a senior professorial lecturer in government at American University, notes that young people are exposed to a range of views, ideas and issues at college. In addition to what they learn in class, students get information from friends, classmates, roommates, campus events, athletic activities and student organizations such as fraternities, sororities, academic clubs and multicultural organizations.

Bailey points out that students impact one another through virtually every facet of the college experience.

“I think sometimes we’re not paying attention to the environment in which students are making decisions,” says Bailey, who has written or coauthored several academic papers on young voters.

Research summaries

Below are summaries of five academic papers as well as links to other resources we think will be helpful to journalists reporting on young voters. We plan to update this piece with new data and research studies as they become available.

Understanding young adults’ political preferences

Unpacking Young Adults’ Voting Preferences: The Role of Neighborhood Trust

Aaron A. B. Thompson and Nathan D. Martin. American Behavioral Scientist, October 2024.

The study: Researchers look at how young adults’ voting preferences are affected by factors related to their neighborhood, including population density, racial diversity, how much they trust local police and how trustworthy they perceive their neighbors to be. Researchers analyzed data collected as part of the Arizona Youth Identity Project. A total of 1,376 likely voters in Arizona aged 18 to 30 years completed an online survey in the lead-up to the 2020 presidential election.

About 44% of respondents were white while 37% were Hispanic, 6% were Asian, 6% were multiracial, 4% were Native American and 3% were Black. Meanwhile, 31% of respondents were men and 69% were women.

The findings: Young adults who considered their neighbors trustworthy were more likely to say they planned to vote for Trump in the 2020 election. Those who expressed higher levels of trust in local police also were more likely to say they would vote for Trump. Although prior research has found that support for Trump is higher in rural areas than in larger cities, researchers found that, for young adults in Arizona, living in a densely populated area was associated with plans to vote for Trump.

The researchers note that there was not a direct association between racial identity and trust in police among the young adults in this study. However, those who lived in neighborhoods where most residents were white had higher levels of trust in police. Researchers add that support for Trump was highest among white young adults who lived in neighborhoods where most residents were racial or ethnic minorities.

In the authors’ words: “In our study, we explore dimensions of neighborhood trust and their relationship to political choice. We find that levels of trust in one’s neighbors and, especially, trust in local police are more strongly associated with political affiliations than sociodemographic characteristics such as race or gender identity. Additionally, in our sample of Arizona young adults, higher levels of neighborhood trust are significantly associated with intentions to vote for Trump in the 2020 election.”

You Voted for Who? Explaining Support for Trump among Racial and Ethnic Minorities

Griffin M. Petty, Dustin Magilligan and Mandi Bates Bailey. New Political Science, May 2022.

The study: Researchers surveyed college students in fall 2020 to better understand their political views, including why some Black and Hispanic students supported re-electing Donald Trump that year despite racist and denigrating statements he had made about Black and Hispanic people. A total of 528 students from several unnamed universities completed the survey. Of those who participated, about 35% identified as Black or African American, 7% identified as Hispanic or Latinx, 50% identified as white and 70% were women. More than 92% were between the ages of 18 and 22.

The findings: Half of the 528 respondents reported being affiliated with the Democratic Party, 24% said they are affiliated with the Republican Party and 26% reported not being affiliated with either political party. The researchers found that Black, Hispanic and white students who agreed more strongly with the statement, “I feel safe with Donald Trump as president,” were more likely to say they voted for Trump or planned to vote for him. Black and Hispanic students who said they believe the Bible to be “the actual word of God” and that it should be “taken literally” were more likely to say they voted for Trump or planned to vote for him, compared with students who said they believe the Bible is the “inspired word of God” or “a book of fables written by men.”

The researchers write that Terror Management Theory, which posits that people develop certain views and opinions based on fear of death, could explain why some Black and Hispanic students support electing Trump to a second term as president. They note that some racial and ethnic minorities may prioritize their immediate safety over values they see as more abstract, such as democracy and equality.

They note that Trump has made statements about Americans being in immediate danger. He has repeatedly referred to unauthorized immigrants as rapists and criminals.

“By using incendiary language, he creates a sense of unavoidable and unpredictable fear that could lead to a falsely exaggerated sense of morbidity,” the researchers write. “In other words, as [Terror Management Theory] would suggest, Trump’s language reminds individuals of the inevitability of death and they consequently attempt to defend themselves against threats (i.e., support and vote for Trump to save themselves).”

In the authors’ words: “The application of [Terror Management Theory] … pushes future research to consider that perceptions of immediate safety may be of greater importance to minorities than what they see as more abstract values (e.g., liberty, democracy, equality). This is troubling as it implies that some of those (albeit a small portion) with the greatest need for societal change can be cajoled and manipulated into voting against their own best interests when fear tactics are employed.”

How out-of-state college students decide where to vote

Closeness and Strategic Participation: Does the Relative Closeness of the US Presidential Elections Shape Where College Students Register to Vote?

Jacob M. Montgomery and Min Hee Seo. The Journal of Politics, April 2022.

The study: When students leave home to attend college in another state, which address do they use to register to vote in a presidential election — their home address or their address at college? That’s the question researchers aimed to answer by surveying 960 college students in the swing state of North Carolina and analyzing administrative records for more than 1 million out-of-state students nationwide.

Researchers examined the results of the survey, conducted in October 2008 and completed by out-of-state students attending an unnamed university in North Carolina. For their main analysis, researchers examined data retrieved from the National Study of Learning, Voting, and Engagement and matched it to data gathered from national voter files for the 2012 and 2016 presidential elections.

The findings: Out-of-state students were more likely to register to vote in the state where they thought the presidential race would be closer. Out-of-state students attending the university in North Carolina were more likely to register to vote in North Carolina if they came from states where the presidential election was less competitive. But they registered to vote in their home states if the race looked like it would be tighter there. “Around 30% of voters in Florida and Pennsylvania indicated they would register in North Carolina compared to nearly 80% of students from New York and Massachusetts,” the researchers write.

When the researchers examined national administrative data and election records, they discovered a similar pattern. They offer this example: “Students from West Virginia attending college in Pennsylvania are expected to be 65% more likely to register in their campus state relative to a student from Pennsylvania attending college in West Virginia (12.7% vs. 7.7%).”

The researchers point out that their findings do not support the “overblown claims about undue election influence” that some politicians have made. “In 2016, Hillary Clinton defeated Donald Trump by fewer than 3,000 votes in New Hampshire, making it one of the closest states,” they write, adding that more than 10,000 out-of-state college students attended schools in New Hampshire. “However, only 2,183 registered in New Hampshire.”

In the authors’ words: “[Out-of-state college students] can be influential, but only for extremely close races. In our view, politicians worried about college students’ votes might do better to focus on earning the support of the tens of thousands of registered in-state students rather than disenfranchising the rest.”

Colleges’ impact on young voter turnout

Which Colleges Increase Voting Rates?

D’Wayne Bell, John B. Holbein, Samuel J. Imlay and Jonathan Smith. Working paper from the Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University, February 2024.

The study: This working paper compares the voting rates of U.S. students at more than 2,000 colleges and universities during presidential elections held from 2004 to 2016. The researchers analyzed data for a combined 21.3 million college students from three sources: national voting records, National Student Clearinghouse enrollment records, and administrative data collected from three tests the college students took while they were in high school — the SAT college-entrance exam, the Preliminary SAT and end-of-course Advanced Placement tests.

The researchers focus on college students who graduated high school between 2004 to 2012 and were eligible to vote in a general election during their last year of high school.

Key findings: Student voting rates varied by institution, ranging from a low of 10% to a high of 60%. The researchers compared colleges and universities by type, and do not disclose the names of individual schools. They found that the most selective institutions generally had the highest student voting rates during the years studied. Community colleges had the lowest.

Researchers found that student voting rates at R1 research universities — a designation the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education gives to universities that offer doctoral degrees and rate “very high” on Carnegie’s research activity index — were 2.7 percentage points higher, on average, than the voting rates of colleges where the highest degree offered is an associate’s degree. Researchers also discovered that institutions that “serve more students, fewer in-state students, fewer Pell grant recipients, and more Black students have relatively higher voting rates.”

Nearly all schools increased the probability that young adults vote, the researchers add. The voting rate of community college students was, on average, 11 percentage points higher than the voting rate of adults from the same age group who did not go to college. “The college one attends matters when it comes to voter turnout, but not as much as attending college itself,” the researchers write.

In the authors’ words: “Our results show that colleges play a formative role in their students’ voting habits. This suggests that institutions of higher education, which enroll nearly 70% of 18-19 year olds, can play an important part in efforts to boost young adults’ [voter] turnout.”

Educating Students for Democracy: What Colleges Are Doing, How It’s Working, and What Needs to Happen Next

Elizabeth A. Bennion and Melissa R. Michelson. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, November 2023.

The study: Researchers examine the college student voting movement and strategies U.S. colleges and universities have used to boost student voting rates. They note that some schools have boosted turnout significantly and point to Northwestern University and Northeast Mississippi Community College as examples. At Northwestern University, student voter turnout rose from 49% in 2012 to 64% in 2016, they write. At Northeast Mississippi Community College, turnout jumped from 31.5% to 54% during the same period. The researchers also suggest ways higher education administrators can strengthen their voter mobilization efforts.

Key findings: Data suggests that when colleges and universities participate in national voting initiatives such as the ALL IN Campus Democracy Challenge, student voting rises. The researchers also note that classroom-based voter registration drives at high schools and higher education institutions work. A 16-campus study conducted in 2006 found that every 10,000 students targeted yielded 600 voter registrations and 260 votes, they add.

“A review of the literature on successful [Get Out the Vote] techniques makes one thing clear: the most effective way to mobilize new voters is to catch their attention and to personalize the invitation to vote in ways that make them feel as if their vote is significant — as if they are more than a number and somebody cares if they, as individuals, go to the polls,” the researchers write.

The researchers point out that research indicates sending college students emails directing them to a state’s online voter registration portal can raise registration rates slightly. There is some evidence, they write, that “relatively passive registration tactics like downloadable forms can increase turnout when paired with follow-up text messages reminding voters to mail the form into the proper offices.”

The authors of the paper also stress the need for more research, especially as it relates to best practices for civic education at the college level.

In the authors’ words: “As we chart a course for the future of civic learning and democratic engagement at the college level, we need more research, particularly into how civic education can create lifelong voters who not only cast informed ballots in every election but stay engaged in their communities. Making electoral participation part of the campus identity and integrating civic engagement into the curriculum and co-curriculum is an important place to start.”

5 story ideas from researchers who study young voters

Bailey, Holbein and Michelson shared five ideas for stories they think journalists should pursue. Michelson notes that teaming up with a student journalist would help strengthen that coverage.

“I’ll bet student journalists can have a very different conversation with students than journalists who just show up on campus and try to talk to students or to campus administrators,” says Michelson, a former student journalist at the Columbia Daily Spectator. “On a lot of campuses, there’s probably a robust group of student journalists who would be amazing resources, because they know what’s been going on, on campus, all year — and that would be amazing context.”

- Voting rate differences: Investigate why young adults’ voting rates vary significantly among states. When CIRCLE researchers examined data for the 2022 midterm election in 40 states, they learned that turnout rates for voting-eligible Americans aged 18 to 29 ranged from 12.7% in Tennessee to 23.2% in North Carolina and 35.8% in Michigan.

- The diverse perspectives of young voters: What are common characteristics of voters aged 18 to 29 and what issues are most important to them? How are they different? What are the common myths and misperceptions about them that need to be dispelled?

- Colleges’ efforts to encourage voting: What are higher education institutions in your area doing to educate students about elections, help them register to vote and encourage voting? Which strategies have worked best?

- Choosing political parties: College students exposed to new ideas and perspectives can develop views that differ drastically from their parents’. How do college students decide which political party to join and which candidates to support when they do not want to ask their parents for help and campus efforts strive to provide nonpartisan information?

- Young adults who do not go to college: Do college students and young adults who don’t go to college face different challenges when registering to vote or casting a ballot? For those who overcame those challenges, how did they do it?

Holbein says asking about college efforts would help researchers like him better understand the role colleges play in changing students’ voting habits.

“One of the things we don’t know from our research is why some colleges are really good at getting people to vote and some are not,” he says. “I’d love to see more coverage of young people who don’t go to college and a little bit more unpacking of why colleges are so important [in generating interest in voting].”

More research on young voters

- The Stubborn Unresponsiveness of Youth Voter Turnout to Civic Education: Quasi-Experimental Evidence From State-Mandated Civics Tests: This paper, published in September 2023, finds that requiring high school students to pass a civics exam to graduate does not encourage young adults to vote.

- “Isn’t It Terrible That All These Students Are Voting?”: Student Suffrage in College Towns: This May 2024 paper examines efforts to prevent college students from voting after the voting age for all Americans was lowered to 18 in 1971.

- Rock the Registration: Same Day Registration Increases Turnout of Young Voters: This paper, published in January 2022, finds that allowing Americans to register to vote on the same day they vote increases turnout most among voters aged 18 to 24.

Other resources for journalists covering higher education

- Reporting on DEI in higher education: 5 key takeaways from our webinar: Three researchers offered journalists tips and insights to help strengthen news coverage of college programs aimed at improving student diversity, equity and inclusion. We highlight five of the biggest takeaways from our April 2024 webinar.

- Improving college student mental health: Research on promising campus interventions: Hiring more counselors isn’t enough to improve college student mental health, scholars warn. We look at research on programs and policies schools have tried, with varying results.

- 5 tips to help you cover the college mental health crisis: We asked Gino Aisenberg, co-director of the Latino Center for Health at the University of Washington, and Tony Walker, senior vice president of academic programs at The Jed Foundation, for advice on how journalists can improve their coverage of college student mental health. They shared these five tips.

- Race-neutral alternatives to affirmative action in college admissions: The research: How can U.S. colleges maintain or improve student diversity now that the Supreme Court has ruled it unlawful to admit students based partly on race and ethnicity? We look at research on the effectiveness of race-neutral alternatives.

- Elite college admissions: A preference for athletes and legacy students: How much of an edge do athletes and the children of alumni have when they apply to highly selective colleges and universities? How do these applicants compare to others in terms of test scores and other measures of academic ability? We’ve gathered research that looks at these questions and more.

Photo by VCU Capital News Service obtained from Flickr and used under a Creative Commons license.

Expert Commentary